The sound of a Harvard Commencement, for many, is the sound of choirs singing—exposed, organic, human. "To write for voices alone is a great challenge—it's one of the purest tests of a composer's craft and ingenuity," says Richard Beaudoin, preceptor of music. The subtleties of the unaccompanied voice have occupied much of his time and concentration lately: President Drew Faust commissioned Beaudoin to write a setting of Seamus Heaney's poem "Villanelle for an Anniversary" for this year's Commencement. The poem was commissioned for the University’s 350th anniversary extravaganza in 1986; its reappearance this year marks the end of commemorating Harvard’s 375th anniversary. "It seemed especially fitting to mark the end of our anniversary celebration by commissioning a work that would draw on the University’s shared history while at the same time creating something new," Faust wrote in an e-mail. The new choral work will premiere immediately after Heaney himself recites the poem, taking a place among the Latin and English of hymns and anthems used for centuries at Harvard. (Raising the status of the arts at Harvard has been a central theme of Faust's presidency, and musical interludes have become a Commencement fixture: Wynton Marsalis played "America the Beautiful" on Commencement Day 2009, when he received an honorary degree, and Plácido Domingo serenaded fellow honorary degree recipient Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2011.)

Heaney's poem seems to have succeeded much better than many other poets' occasional verse. It appears in Heaney's career-spanning volume of selected poems, Opened Ground, and he expressed fondness for it when he returned to give a reading of his work in the fall of 2008—though as far as villanelles were concerned, he noted, "it should be [my] last": the villanelle, a 19-line verse form defined by strict rules governing rhyme and repetition, demands severe poetic discipline, and successful examples are rare. Heaney's begins:

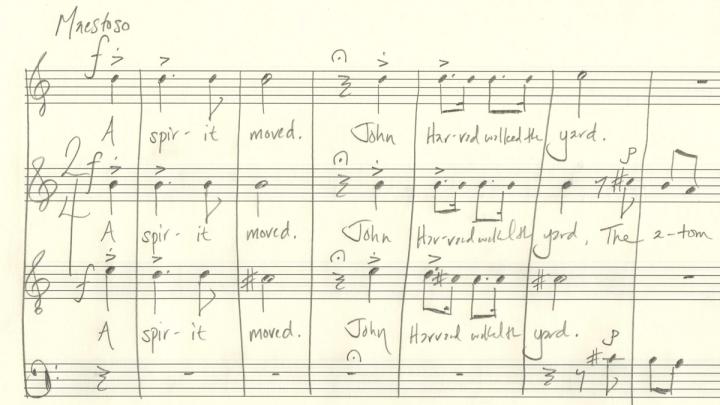

A spirit moved. John Harvard walked the yard,

The atom lay unsplit, the west unwon,

The books stood open and the gates unbarred.

Beaudoin encountered problems similar to those Heaney himself faced—how to make great art for a public ceremony, and how to work with a tightly regimented structure—in interpreting and setting Heaney's text. Although many of Beaudoin's other compositions belong to the avant-garde, he explains that he responded specifically to the occasion: "This piece is designed to be sung at a large gathering such as Commencement, and to engage the musical strengths of the students in the Harvard Commencement choir." Andrew Clark, senior lecturer on music and director of choirs, who will be conducting the premiere, adds, "Just as Heaney considered the context of reciting the villanelle—outdoors, through amplification, to…thousands of listeners—Richard had the same idea in mind for his piece. It's exuberant and euphoric and at the same time very well crafted."

Beaudoin remarks that the careful construction of the poem itself inspired distinctive creative directions for its setting. "In music, making a memory usually involves bringing back some part of the piece that occurs earlier—and in the poem, you already have these lines which recur. The principle, for me, was to respond to those repetitions, but each time to recontextualize them musically." Beaudoin begins with two phrases for the villanelle's two recurring lines, but transforms them on each successive reappearance—by elaborating on a harmony, altering a melodic line, doubling the length of a rhythmic pattern. "This is what drives the piece, and the poem itself, through to its conclusion, when the first lines of the poem are brought back," he explains. "The closing return acts as the fruition of all of the meanings that have attached themselves to these lines throughout the poem." In this final stanza, the choir circles once more to the lines that opened the villanelle:

Begin again where frosts and tests were hard.

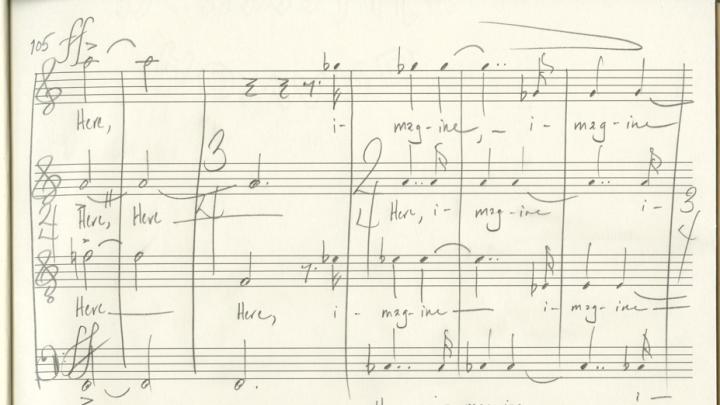

Find yourself or founder. Here, imagine

A spirit moves, John Harvard walks the yard,

The books stand open and the gates unbarred.

Lines that had been pronounced in rhythmic unison now fold contrapuntally over one another, before returning to insist on their conclusion repeatedly: "the books stand open, and the gates—the books stand open and the gates—the books..." the choir reiterates, before resolving onto an intimate chord that swoops up suddenly to a bold forte in volume.

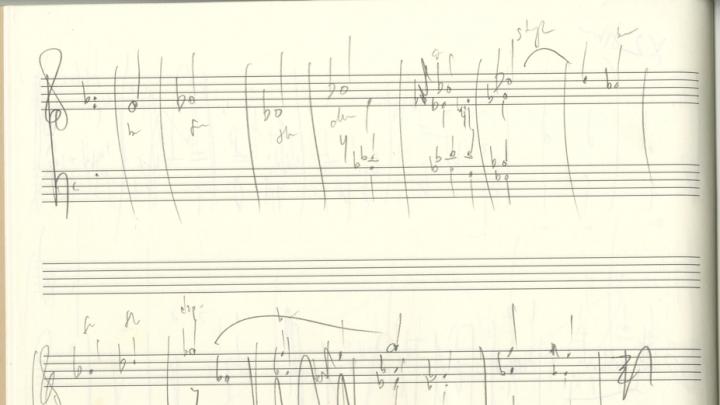

Beaudoin's setting mantles itself with haunting grandeur, frequently wielding many open intervals between a pair of voices that dissent tersely from the other pair: sets of spectrally unconfined fifths and ninths intersect at crunching seconds with the other voices. At climaxes, the parts spread wildly; chasms open between the zenith of the top sopranos and the nadir of the bass. In rehearsals on the Thursday before Commencement, Clark talked his choir through the patterns of musical influence at work. "Hear the Samuel Barber moment with the A in the soprano, then the bass?" he asked rhetorically. Of the words "Find yourself or founder," he inquired, "What does this remind you of?" Someone in the tenors volunteered the wilder moments in the last movement of Beethoven's ninth symphony. "Right, I think so," Clark agreed. He also noted, "I think [Richard] has a keen awareness not just of the capabilities of the choir, but also of the kind of music that the choir really likes to sing."

The piece nestles a steady resolution within a steadily churning sense of longing, perhaps of homesickness. The strange weave of voices across phrases that settle on cautious but determined dissonances echoes against the harmonies of familiar works, opening a musical equivalent of the uncanniness of historical memory—the feeling of seeing a photograph of Harvard Yard in the 1930s, the 1880s, or a in a painting from the eighteenth century. The piece gestures toward the Yard itself: a grand pause intervenes after the chorus sings, "Nothing stirred," highlighting the presence of location in the music. Strands of probing eighth notes wreathe Heaney's retrospective assertion that "The future was a verb in hibernation" as if to excavate the moment when our present was that future. And suddenly the texture of speech punctures the fabric of the music where parentheses enfold a quiet imperative:

Was that his soul (look) sped to its reward

By grace or works? A shooting star? An omen?

"A composer has to ask a new question of the poem at a moment like that," Beaudoin says. "One cannot simply sing the words as they come and expect that the 'parentheticalness' of that word will speak itself." The entire process of composition circles around to the music latent within the text, he explains—a process of interrogation, interpretation. "It was the villanelle itself that made me agree to the commission and be engaged in setting it. Really the poem itself is the source of the piece." Asked about what he wants to express through his setting, he says "it is in sound what Professor Heaney's poem is in words....I don't know a better way to explain it."