Editor’s note: Spencer Lenfield ’12 reported on the unique loan of Itō Jakuchū’s magnificent works to the National Gallery of Art in the March-April Harvard Magazine; see also his video interview with curator Yukio Lippit, professor of the history of art and architecture, which features images from the exhibition. This week, Lenfield traveled to Washington, D.C., to report on the preparations for the opening of the exhibition; this is his dispatch.

The 30 paintings that comprise the mid-eighteenth-century Japanese painter Itō Jakuchū’s suite Colorful Realm of Living Beings (opening to the public today at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.) hang in a long, rectangular room, with 15 paintings on each side, illuminated under dim, delicate light. The effect, when you walk in, is like being in a hallway of windows at dusk—if adjacent windows could hold views as impossibly different as a duck in a snowy pond, birds nestled high in a tree, and roosters circling each other cagily beneath tropical palms. On the short side of the room, opposite the main entrance, a triptych of the Buddha flanked by two Bodhisattvas gazed directly at me with a somewhat discomforting penetration; I felt like I was in a highly spiritual menagerie with a particularly intimidating set of security guards.

The exhibit marks the only occasion on which the Colorful Realm has been shown with the triptych outside Japan. Even in Japan, noted Ambassador Ichiro Fujisaki, the entire suite of paintings is “rarely displayed all at once—usually only a few paintings at a time”—and the paintings reunite with the triptych only once a year at Shōkokuji Monastery in Kyōto for an annual repentance ritual in recognition of Kannon, the Bodhisattva of compassion.

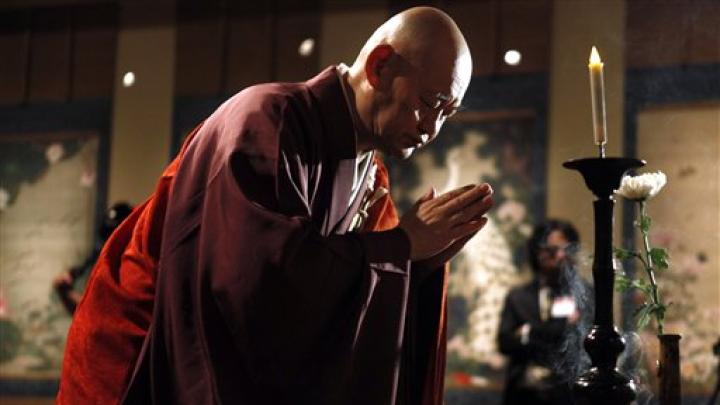

The monastery was Jakuchū’s spiritual home during his lifetime, and on March 26, Buddhist monks from Shōkokuji traveled to the National Gallery to bless the paintings as they began their time in the United States. A small altar in front of the triptych held a simple pot of incense, a vase with a single chrysanthemum, and a steady candle. The weighty smell of beeswax and pine filled the gallery as the monks offered prayers to Kannon for the comfort of Jakuchū’s soul and for peace in the world. The superintendent of the monastery, Reverend Raitei Arima, clad in robes of carmine and purple, bowed his head to the floor before the altar, and one of the monks repeatedly struck a bell that keened shrilly over the low chanting of liturgy; another murmured the text of the Heart Sutra in scriptural Chinese:

All things are empty:

Nothing is born, nothing dies,

nothing is pure, nothing is stained,

nothing increases and nothing decreases.

I asked Arima—a tall man with a gentle smile and shaven head—why the monastery thought it was important to bless the exhibit as it opened, surely an unusual step in the presentation of most art. “These paintings are painted based on the spirit of Buddhism,” he told me. “All the creatures and plants you see in the paintings are blessed by the Buddha, and they exist in this world. Insects, birds, fish, and all the animals and plants painted by Jakuchū with such beautiful color explain the importance of life.”

Exhibit curator Yukio Lippit said the memorial and dedication ceremony accurately reflected the original context and use of the paintings. “When Jakuchū donated 24 works from the set in 1765 to the Zen monastery Shōkokuji, he also soon after established his own tombstone, and in his dedicatory inscription he was already discussing his own interment, his own burial at Shōkokuji, and commemorative rituals for himself—and he anticipated these works as a backdrop for those rituals.”

And as impressed as I was, while researching the first article on Yukio’s work on the exhibit, by the quality and sophistication of the artwork, it is undeniable that there is something essential about seeing these paintings in person, when you can understand the character of a brush stroke, and the degree to which the fabric absorbed the pigment, or whether the pigment is lacquered, frosting-like, on top. One of the paintings in the suite, “Plum Blossoms and Moon” (ca. 1759-61), didn’t really make sense until I saw the delicacy and “pop” of the yellow at the tips of the plum anthers. Similarly, the triptych in the center captures the richness of fabric and its flow: the application of color is cel-like, with only hints of shadow.

One understands the paintings best by viewing them from multiple perspectives—and this means the relatively fixed perspective of reproduced images always loses something of the impression produced by the originals, which are about five feet tall. The paintings work from a distance as compositional wholes, with a geometry, a rhythm, and a manipulation of space and absence that are absolutely remarkable—like the blank space in “Wild Goose with Reeds” (1765-66), where it’s not clear where cracked ice ends and sky begins. But when you stand close to the works, you wonder how anyone could ever make any sense of them at all without pressing his nose against the glass, straining to get a closer look at the texture of the silk on which the paint is applied, or the fine rendering of close detail. Jakuchū’s paintings put the world under a microscope, exquisitely rendering the mottling on birds’ feathers, the fungus on leaves. There is a quasi-scientific cast to many of the paintings, which show an attention to detail prized by field biologists—especially the later works, like “Fish” (1765-66).

But at the same time, the paintings manage to reconcile the particular and the miniature with the coherence of the whole—not just on the level of individual paintings, but through the set as a complete work. The Colorful Realm turns its genre, the “bird and flower” painting of East Asian art, into a metonymy for the richness of nature at large—expanding to encompass fish, roosters, lizards, trees, and insects. One of the most fanciful details of “Fish” is a baby octopus clinging for dear life to one of its mother’s tentacles—Jakuchū demonstrates a capacity not just for close observation, but for wit and imagination.

I didn’t want to stop looking; I didn’t want to leave, in fact, because I knew that as soon as I did, I’d never have the pleasure of seeing them all in one place ever again. But that’s one of the messages implicit in the Colorful Realm: transience is the nature of all pleasure, and also of life in general. The paintings will always continue to exist, but never in quite the same place, or the same way, or in the same city, or for the same audience. As the monks chanted: “Nothing is born, nothing dies, / nothing is pure, nothing is stained, / nothing increases and nothing decreases.”