An historic basketball game was played on January 8 in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Harvard beat Boston College, ranked seventeenth in the nation, 82-70, recording its first-ever win over a nationally ranked opponent. What is more, BC had just defeated the University of North Carolina, then the nation’s top team. (Harvard’s last game against such elite competition, with twenty-third-ranked Stanford, was a 111-56 blowout, the opener of 2007-08’s struggling 8-22 season, when the Crimson tied with Princeton and Dartmouth for last in the Ivies.)

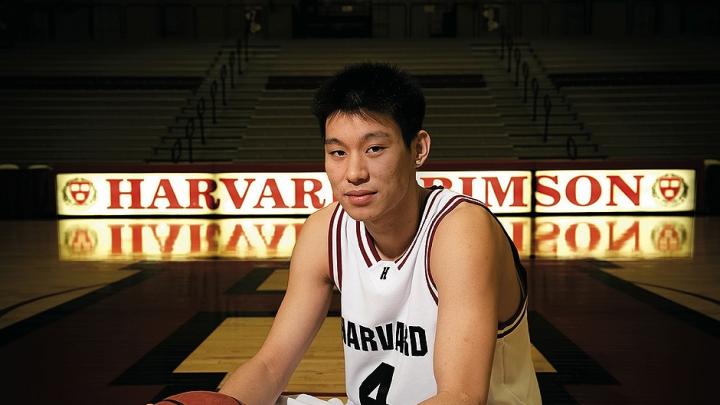

That January night, shooting guard Jeremy Lin ’10 put on a magic show, throwing in 27 points and making eight assists and six steals. On defense, he held BC’s all-American guard (and projected NBA draft pick) Tyrese Rice, who had scorched UNC for 25 points, scoreless in the first half. When Lin finally fouled out with 40 seconds left, there were none of the mocking chants one often hears in college gyms at such moments; instead, the crowd made the air alive with applause. “That game was something I’ll never forget, an emotional high,” says Lin. “It was something our players and coaches deserve—we’ve all worked very hard. We earned it.”

In mid January, when Harvard was 9-6 (1-0 Ivy), Lin was the only college basketball player in the United States who ranked among the top 10 players of his conference in points, rebounds, assists, steals, blocks, field-goal percentage, free-throw percentage, and three-point percentage. That pretty much covers the game of basketball: it’s an extraordinary display of versatility. Lin was averaging 17.9 points and 5.5 rebounds per game, while hitting field goals at a .500 clip, free throws at .802, and three-pointers at .424. Characteristically, he credits his teammates for those high-flying stats. Regarding steals, for example (last year he led the Ivies with 58), Lin notes, “When other guys on the floor are doing a good job defending, that can force a bad pass, and I can grab the ball.”

“I’m trying to do whatever the team needs me to do in that particular game,” Lin explains. “A lot of the time, it’s not going to be scoring, even though that’s what’s most valued when people talk about a game. Sometimes it’s going to be rebounding or passing. It’s a credit to the other guys on our team that I don’t have to be scoring every game: we have several players who can score.”

“I haven’t coached anyone I would regard higher [than Lin],” says Tommy Amaker, who coached 19 years at Duke, Seton Hall, and Michigan before arriving at Harvard’s helm in 2007. “Jeremy is a hard worker, a passionate ball player, a student of the game who loves the game. He’s an unselfish young man, sometimes to a fault. Jeremy’s a complete player, a throwback to the days of yesteryear. He could play basketball in any era. I love coaching him; it’s great to have a player you sometimes have to ask to slow down, instead of ‘Please, take it up a notch.’”

The six-foot, three-inch Lin built his game amid a hoop-playing family. Both parents are Taiwanese immigrants and computer engineers who eventually settled in Palo Alto, California. His father, Gie-Ming, had never heard of the sport when he arrived in the United States in 1977, but soon became a basketball junkie. Though only five feet six, he plays recreationally and collects basketball DVDs. Lin’s mother, Shirley, fell in love with the game as her sons did, and is now a major fan. Older brother Joshua played for Henry M. Gunn High School in Palo Alto; Jeremy played for the rival Palo Alto High School, where his younger brother Joseph is on the team now. “Anyplace we could find a hoop and a ball, we would play,” Lin says. After their Friday-night youth group at the Chinese Church of Christ, for example, the Lin brethren would adjourn to a gym at Stanford for some pick-up games that might last until 2:00 a.m. Lin came to Harvard—not Stanford, Cal, or UCLA—in part because he wanted to play college basketball. Now Amaker feels Lin is skilled enough to have a career after college if he wants one. (Lin admits that playing in the NBA would be “a dream come true”—his youthful idol was Michael Jordan—but the economics concentrator considers pro ball a long shot. He aspires to work for a church (and serving an underprivileged urban community.)

But for now there is the holy grail of Harvard basketball—an Ivy League championship—which the Crimson has yet to bag. Last year Cornell ran the table at 14-0 and graduated no starters; in preseason polls, Harvard wasn’t picked to finish higher than third. On the other hand, before this season, Harvard had never beaten a team like Boston College.