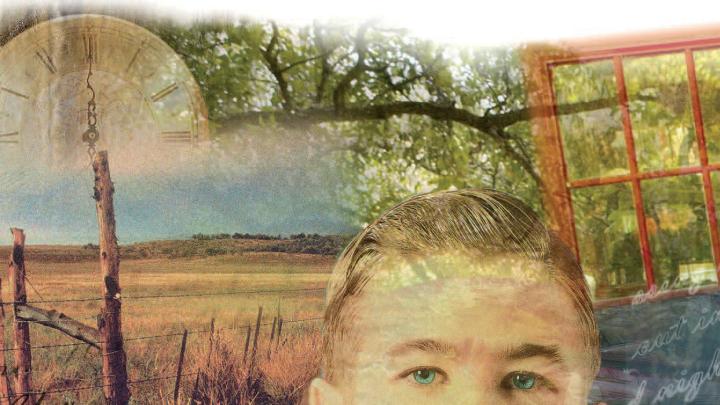

Robert Creeley ’47 died on March 30, shortly after being named the poet for the Literary Exercises conducted annually by Harvard’s Phi Beta Kappa chapter during Commencement week. In his memory, at what would have been a fitting homecoming (Creeley was born in Arlington, which borders Cambridge, and first published his poetry in an undergraduate literary journal), portions of a recent work, “Caves,” were read during the ceremony.

|

Phi Beta Kappa vice president Judith Vichniac noted that the prolific Creeley had published more than 60 books. Her brief narrative also hinted at the wide geographic reach of his energetic life: he left Harvard in 1944 to become an ambulance driver in India and Burma for the American Field Service. He returned for a year, married, and dropped out again without completing his degree. Later stopping points included a farm in New Hampshire; France and Majorca; the experimental Black Mountain College, famously associated with Franz Kline, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Paul Goodman, where Creeley taught and edited the Black Mountain Review; the San Francisco of Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and other poets; the University of New Mexico; SUNY-Buffalo; and, most recently, Brown University. Citing the Bollingen Prize judges, Vichniac noted the “stubbornly plain language” of Creeley’s “instantly recognizable,” pared-down poetry.

Porter University Professor Helen Vendler, who read the selections, made it clear that “plain” need not mean simple or easy. In 2004, Creeley visited French caves renowned for their prehistoric paintings, and, she said, was moved to consider the impact and influence of caves, their stone walls as a medium, and the paintings made upon them.

As an introduction to her reading, Vendler briefly interpreted her four selections in light of that experience. The first section recalls a child’s love of caves and spaces where he found solitude and room for the making of art. The third captures the astonishing experience of entering the caves in France and seeing the works that unknown artists were compelled to make on those dark walls. The difficult fourth section metaphorically recapitulates life from the birth passage to death, as the poem moves toward the suggestion that art is the legacy to posteritythe answer Creeley found to the “what’s left” at the conclusion of the sixth and final section, where he explains the difficulty of art-making: the struggle to keep current with life even as one captures its echo passing by.

“Caves” appears here, complete, by courtesy of Penelope Creeley, who married Robert Creeley in 1977. She was present in Sanders Theatre for the reading on June 7.

~The Editors

Caves

So much of my childhood seems

to have been spent in rooms

at least in memory, the shadespulled down to make it darker, the

shaft of sunlight at the window’s edge.

I could hear the bees then gatheringoutside in the lilacs, the birds chirping

as the sun, still high, began to drop.

It was summer, in heaven of small town,hayfields adjacent, creak and croak

of timbers, of house, of trees, dogs,

elders talking, the lone car turning somedistant corner on Elm Street

way off across the broad lawn.

We dug caves or else found them,down the field in the woods. We had

hacks we built after battering

at trees, to get branches, made tepee-like enclosures, leafy, dense and in-

substantial. Memory is the cave

one finally lives in, crawls onhands and knees to get into.

If Mother says, don’t draw

on the book pages, don’t colorthat small person in the picture, then

you don’t unless compulsion, distraction

dictate and you’re floating offon wings of fancy, of persistent seeing

of what’s been seen here too, right here,

on this abstracting page. Can I use the green,when you’re done? What’s that supposed to be,

says someone. All the kids crowd closer

in what had been an empty roomwhere one was trying at least

to take a nap, stay quiet, to think

of nothing but oneself.

2

Back into the cave, folks,

and this time we’ll get it right?Or, uncollectively perhaps, it was

a dark and stormy night heslipped away from the group, got

his mojo working and beforeyou know it had that there

bison fast on the wall of the outcrop.I like to think they thought,

though they seemingly didn’t, at leastof something, like, where did X put the bones,

what’s going to happen next, did she, he or itreally love me? Maybe that’s what dogs are for,

but there’s no material survivingpointing to dogs as anyone’s best friend, alas.

Still here we are no matter, still hacking away,slaughtering what we can find to, leaving

far bigger footprints than any old mastodon.You think it’s funny? To have prospect

of being last creature on earth or at best acompany of rats and cockroaches?

You must have a good sense of humor!Anyhow, have you noticed how everything’s

retro these days? Like, something’s been here beforeor at least that’s the story. I think one picture is worth

a thousand words and I know one cave fits all sizes.

3

Much like a fading off airplane’s

motor or the sound of the freewayat a distance, it was all here clearly enough

and no one goes lightly into a cave,even to hide. But to make such things

on the wall, against such obviouslimits, to work in intermittent dark,

flickering light not even held steadily,all those insistent difficulties.

They weren’t paid to, not that we know of,and no one seems to have forced them.

There’s a company there, tracksof all kinds of people, old folks

and kids included. Were they havinga picnic? But so far in it’s hardly

a casual occasion, flat on back withthe tools of the trade necessarily

close at hand. Try lying in the darkon the floor of your bedroom and roll

so as you go under the bed andask someone to turn off the light.

Then stay there, until someone else comes.Or paint up under on the mattress the last

thing you remember, dog’s snarling visageas it almost got you, or just what you do

think of as the minutes pass.

4

Hauling oneself through invidious

strictures of passage, the height

of the entrance, the long twisting

cramped passage, mind flickers, a lamp

lit flickers, lets image project

what it can, what it will, see there

war as wanting, see life as a river,

see trees as forest, family as

others, see a moment’s respite,

hear the hidden bird’s song, goes

along, goes along constricted, self-

hating, imploded, drags forward

in imagination of more, has no

time, has hatred, terror, power.

No light at the end of the tunnel.

5

The guide speaks of music, the

stalactites, stalagmites making a

possible xylophone, and some

Saturday night-like hoedown

businesses, what, every three

to four thousand years? One

looks and looks and time

is the variable, the determined

as ever river, lost on the way,

drifted on, laps and continues.

The residuum is finally silence,

internal, one’s own mind constricted

to focus like any old camera

fixed in its function.Like all good questions,

this one seems without answer,

leaves the so-called human

behind. It makes its own way

and takes what it’s found

as its own and moves on.

6

It’s time to go to bed

again, shut the light off,

settle down, straighten

the pillow and try to sleep.

Tomorrow’s another day

and that was all thousands

and thousands of years ago,

myriad generations, even

the stones must seem changed.The gaps in time,

the times one can’t account for,

the practice it all took

even to make such images,

the meanings still unclear

though one recognizes

the subject, something has

to be missed, overlooked.No one simply turns on a light.

Oneself becomes image.

The echo’s got in front,

begins again what’s over

just at the moment it was done.

No one can catch up, find

some place he’s never been to

with friends he never had.This is where it connects,

not meaning anything one

can know. This is where

one goes in and that’s what’s to find

beyond any thought or habit,

an arched, dark space, the rock,

and what survives of what’s left.

Copyright © 2005 by Robert Creeley