Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

A famous maxim found in Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy states, "A dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant may see farther than a giant himself." I think most of those who became psychoanalysts in my generation assumed that this maxim had to be true. Whether critical of Freud, as some people were, or reverential, as we were here in Boston, we all hoped to be able to see farther than the giant and to build on the foundation Freud had begun.

The most beautiful and moving description of the collective enterprise at that time was given by John Murray at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society. In presenting his interesting insights into narcissistic entitlement, he compared what we were doing to the construction of the great cathedral at Chartres, where workers toiled for more than a century, and declared that he would be satisfied with his career if he had placed one brick in the conceptual cathedral of psychoanalysis. Although Murray was more impassioned than most of my teachers in psychoanalysis, I think at some level they shared his conviction and tried to pass it on to us.

Unfortunately, I and many others in my generation have lost that sense of conviction and with it, the feeling that we are part of a collective enterprise. To us, the maxim about dwarfs standing on giants seems untrue or, at least, inapplicable to psychoanalysis. Those who stand on Freud's shoulders have not seen farther, they have only seen differently-and often they have seen less. Rather than building a cathedral, psychoanalysts have built their own churches. Consider from this perspective the two great women, Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, who dominated psychoanalysis after Freud's death. Each of them thought she was standing on Freud's shoulders and extending his true vision. And their adherents certainly believed they were building Freud's cathedral and accommodated both their psychoanalytic practice and thinking accordingly. Today, at least in my opinion-and I am not entirely alone in thinking this-neither Anna Freud's ego psychology nor Melanie Klein's object relations theory seems like a systematic advance on Freud's ideas. Rather they seem like divergent schools of thought, no closer to Freud's work than are the theories of Karen Horney, who rebelled against Freudian orthodoxy.

Whatever they may have thought they were doing, these distinguished leaders of psychoanalysis, and those who followed after them, have not been able to stand on Freud's shoulders and achieve the production of cumulative knowledge. In subsequent years the proliferation of divergent schools undermined the basic theoretical language of psychoanalysis. The distinguished psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut explained that it had become impossible to base his work on his predecessors' because he would have been entangled "in a thicket of similar overlapping, or identical, terms and concepts which, however, did not carry the same meaning and were not employed as a part of the same conceptual context."

The collapse of conceptual solidarity is now felt at the very center of psychoanalysis-among the self-declared Freudians. This is the diagnosis of Leo Rangell and Merton Gill, two leading figures of the American Freudian center. Gill, one of my first teachers and a wonderfully candid man, described the situation as follows: "Psychoanalysis seems to be in particular disarray...while there have always been dissenting voices and even new schools...the organized center seems to be less a majority viewpoint...." He worried that this was a "portent of the dissolution of the conceptual framework."

What is there about Freud's vision that has made his monumental work a limiting factor rather than a scaffolding on which others can stand? Put less metaphorically, why has psychoanalysis not become a cumulative discipline? I believe the answer to this question will tell us something about where psychoanalysis will survive. The answer is that psychoanalysis, both as a theory and as a practice, is an art form that belongs to the humanities and not to the natural sciences. It is closer to literature than to science and therefore-although it may be a hermeneutic discipline-is not a cumulative discipline. When one human being analyzes another, the result is not an objective scientific explanation that can be separated from the subjectivity of the analyst. Unable to move toward the objectivity of science, we are retreating into our own subjectivity. Looking back at what we now know about Freud, I think the case can easily be made that Freud was more an artist/subjectivist/philosopher than a physician/objectivist/scientist. Ernest Jones in his biography created the legend that Freud, upon graduating from the gymnasium, decided to become a medical scientist because he read a famous essay by Goethe on nature. If Freud was inspired by Goethe's essay, then I suggest it was because he identified with the author, not the medical and scientific content, of the essay.

During the years when Freud was working on The Interpretation of Dreams, he confided to his friend William Fleiss, "As a young man my only longing was for philosophical knowledge, and now that I am changing over from medicine to psychology I am in the process of fulfilling this wish." By the end of his life he felt comfortable enough to inform his readers, "My self knowledge tells me I have never really been a doctor in the proper sense."

If not a "proper" doctor, did Freud consider himself a "medical scientist"? In the late 1890s he wrote, "It still strikes me, myself, as strange that the case histories I write should read like short stories and that, as one might say, they lack the serious stamp of science."

Freud, in fact, had enormous literary talent and when it seemed clear that he would never win the Nobel Prize for medicine, Thomas Mann, along with other literary greats, actually encouraged the nomination of Freud for the Nobel Prize in literature. He was awarded the Goethe prize. Even those like myself who cannot read Freud's German are awed by the power of his rhetoric in translation.

Here is a line from one of his most influential theoretical papers, "Two Principles of Mental Functioning." Describing the momentous significance of the reality principle replacing the pleasure principle, he writes, "The doctrine of reward in the afterlife for the voluntary or enforced renunciation of earthly pleasures is nothing other than a mythical projection of this revolution in the mind." A marvelous subjective speculation-I find it persuasive, but is it empirical? Is it based on objective data? In Civilization and its Discontents, we find: "The more virtuous a man is, the more severe and distrustful is his conscience, so that ultimately it is precisely those people who carried saintliness furthest who reproach themselves with the worst sinfulness." And a final example: "Eternal wisdom, in the garb of primitive myth, bids the old man renounce love, choose death, and make friends with the necessity of dying." The quote is from a piece of Freud's literary criticism; he is discussing Shakespeare's King Lear.

This literary, artistic side of Freud is by all accounts even more prominent in his original German; however, Ernest Jones and the official British translators of Freud's work were particularly determined to present Freud to the readers of English as an empirical scientist. William James, who had gone to hear Freud speak at Clark University, declared him a man of fixed ideas. And Jones worried that Freud might be written off as unscientific and speculative by the English-speaking world. Jones actually convinced Freud to keep some of his theories quiet, at least for a while, among them Freud's belief in ESP and his conviction that the Earl of Oxford had written the plays of Shakespeare.

Jones had good reason to worry on other grounds. I quote Freud's famous letter of February 1900 to Fleiss: "I am not really a man of science, not an observer, not an experimenter, and not a thinker. I am nothing but by temperament a conquistador-an adventurer if you want to translate the word-with the curiosity, the boldness, and the tenacity that belongs to that type of being. Such people are apt to be treasured if they succeed, if they have discovered something; otherwise they are thrown aside. And that is not altogether unjust."

Freud in a much later conversation with Jones allegedly said that, "As a young man I felt a strong attraction toward speculation and ruthlessly checked it." This "ruthless" suppression of speculation is seldom to be found in Freud's collected works. Fifteen years ago I spent most of a year reinterpreting Freud's first dream. This endeavor required me to read carefully all of the available biographical material and the letters of Freud, together with all of his published work in the early years of 1895 and 1896. What one discovers is that Freud had a new hypothesis every day. It is astonishing to see how little evidence he needed; a single patient hour was enough to launch a whole new theory of mental illness.

Freud was no more a scientist than Marx. I say this not in disrespect; both men were geniuses. Freud's Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality is a work of genius that one can still read with amazement. Freud considered it the core of psychoanalysis. These essays provided the twentieth century with a revolutionary reconception of the human condition: psychosexual development and the Oedipus complex. The work is in some sense empirical, and yet Freud provides almost no evidence and no direct observational data for his sweeping conclusions. The unspecified and perhaps unrecognized premise of the work is that the author deals here with the universals of the human condition and every reader, like Freud, has the necessary empirical evidence available and need only be willing to consider his or her own subjective experiences. Although the method is not recognizable as science, I know of no other work in psychiatry or psychology so powerful, so lucid, and so immediately convincing. Inventing two technical terms, sexual aim and sexual object, Freud deconstructs the centuries-old conception of the sexual instinct and in the process illuminates the related significance of sexual foreplay and perversions. It was Freud who brought the sexual outcasts back into the family of humanity and showed us the common themes in all the complicated dances of our erotic life. These ideas for me unequivocally establish Freud's revolutionary genius, but I find no scientific method or science in this great work. Indeed, these essays were too convincing. They are filled with what we now recognize as horrifying mistakes (fixed ideas) about female sexuality that were taken as scientific truth by psychoanalysts. As a result we made several generations of educated women who had satisfying clitoral orgasms feel sexually inadequate and misled them about the possibilities of sexual gratification.

Freud in his later works exemplifies what I have called the noncumulative style in psychoanalysis. Explaining in his brief preface to The Ego and the Id why he had not acknowledged others in the monograph, Freud wrote, "If psychoanalysis [by which he means his own writings] has not hitherto shown its appreciation of certain things, this has never been because it overlooked their achievement or sought to deny their importance, but because it followed a particular path which had not yet led so far. And finally, when it has reached them, things have a different look to it from what they have to others." What he describes is not the collective and cumulative enterprise of science built on the shoulders of those who go before. This is Freud advancing the human project of self-understanding more than any other person in this century-but with the unique subjective vision of the artist and  not through the objective methods of science. Freud did not even feel the need to build with consistency on his own ideas. Kohut's phrase applies as well to Freud as to his followers: the complete psychological works are also a thicket of overlapping, or identical, terms and concepts that neither carry the same meaning nor are "employed as part of the same conceptual context." Scholars like David Rappaport, Heinz Hartmann, Edward Bibring, and Otto Kernberg labored in vain to bring some semblance of order to what I think were flashes of inspired speculation.

not through the objective methods of science. Freud did not even feel the need to build with consistency on his own ideas. Kohut's phrase applies as well to Freud as to his followers: the complete psychological works are also a thicket of overlapping, or identical, terms and concepts that neither carry the same meaning nor are "employed as part of the same conceptual context." Scholars like David Rappaport, Heinz Hartmann, Edward Bibring, and Otto Kernberg labored in vain to bring some semblance of order to what I think were flashes of inspired speculation.

I believe Freud at times recognized that what he was doing was very close to literature. He wrote about creative writers, "One may heave a sigh at the thought that it is vouchsafed to a few with hardly an effort, to salvage from the whirlpool of their emotions the deepest truths, to which we others have to force our way." And again, "Imaginative writers are valuable colleagues. In the knowledge of the human heart they are far ahead of us common folk, because they draw on sources that we have not yet made accessible to science." Clearly Kohut knew this as well. He wrote, "The artist stands, as it were, in proxy for his generation: not only for the general population but even for the scientific investigators of the socio-psychological scene." Freud best described what psychoanalysis is about from this perspective in his paper on his interpretation of Michelangelo's Moses. "Works of art do exercise a powerful effect on me, especially those of literature and sculpture, less often of painting. This has occasioned me, when I have been contemplating such things, to spend a long time before them trying to apprehend them in my own way, i.e. to explain to myself what their effect is due to. Some rationalistic, or perhaps analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me. This has brought me to recognize the apparent paradoxical fact that precisely some of the grandest and most overwhelming creations of art are still unsolved riddles to our understanding. A work of art of this kind needs interpretation, and until I have accomplished that interpretation I cannot come to know why I have been so affected."

Freud managed to see in Anna O, in Elizabeth von R, in the Rat Man, and most importantly in himself the same kind of mystery or riddle he saw in Michelangelo's Moses.

There are, I think, interesting consequences in recognizing-or positing-that Freud was more artist/subjectivist/philosopher than scientist. For one thing, it immediately suggests why it is impossible for us to see farther by standing on his shoulders. It is difficult to imagine anyone claiming that because he stands on Shakespeare's shoulders he can see farther than Shakespeare. Merton Gill, who died in 1994 at age 81, spent his entire life trying to advance Freud's vision, believing that psychoanalysis was a scientific enterprise. In his last book, published in the year of his death, he was forced to acknowledge that psychoanalysis has remained "to a remarkable degree the work of one man, Sigmund Freud." Further on in the book he writes that "systematic research has brought no new 'advances' in psychoanalytic practice or theory," and in a final cri de coeur he echoes Freud's scientific critics, "Let me repeat: We may be satisfied that our field is advancing, but psychoanalysis is the only significant branch of human knowledge (and therapy) that refuses to conform to the demand of Western civilization for some kind of systematic demonstration of its contentions."

Gill steadfastly refused to accept that psychoanalysis was an interpretive discipline rather than a natural science. Plato, Hegel, Kant, Michelangelo, da Vinci, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, and Sartre helped to shape Western civilization and its conception of the human condition without any systematic proofs of their contentions, and so, I suggest, did Freud. I do not think Gill would have taken much comfort from this thought. In his common-sense way he intuited that without its putative scientific roots, psychoanalysis as he knew it would be crippled. That conception of psychoanalysis embodied in the work of Freud held the enterprise together. Even those who disagreed with Freud were anchored and placed in relation to Freud. Now the center does not hold-without the claim of science there is no privileged text.

If psychoanalysis and Freud belong to the arts and humanities, or, as Roy Schafer says, to the hermeneutic disciplines, then that is the domain in which Freud and psychoanalysis will survive. As academic psychology becomes more "scientific" and psychiatry becomes more biological, psychoanalysis is being brushed aside. But it will survive in popular culture, where it has become a kind of psychological common sense, and in every other domain where human beings construct narratives to understand and reflect on the moral adventure of life. One token form of empirical evidence for this proposition: a computer search of Harvard course catalogs for classes whose descriptions mention either Freud or psychoanalysis turned up a list of 40, not counting my own two courses. All of them are in the humanities, particularly literature; no course is being given in the psychology department, and next to nothing is offered in the medical school.

Having addressed psychoanalytic theory, I turn now to the even more vexing predicament of psychoanalytic treatment and psychoanalytic therapy. Here I shall discuss what happens to psychoanalysis if one loses confidence in its supposedly scientific account of human development.

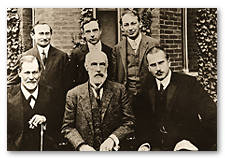

The master in Massachusetts: Freud (left front), Carl Jung (right front), Ernest Jones (center rear), and others at Clark University in 1909. Photograph courtesy Austrian Press and Information Service, New York City |

The construction of narratives as self-descriptions, though usually in much more subtle and convoluted ways, is what much of psychoanalysis is about. Freud generated self-descriptions based on developmental events and psychosexual stages like those he described in Three Essays and The Ego and the Id. That is how we in the twentieth century came to understand our sexual preferences, our foibles, and our character. Now the important challenges for psychoanalytic therapy, as posed by our critics, are first, that these developmental events have no important causative relationship to the phenomena of psychopathology, and second, that the self-descriptions generated by our explanatory theories are both irrelevant and unverifiable.

Early in my career as a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst I believed that every form of mental illness-be it psychosis, neurosis, or personality disorder-could be understood in terms of psychoanalytic developmental stages. If one wanted to understand psychopathology better, one had to learn more about infant and child development. This idea was basic and it was unquestioned.

Our problem is that, in light of the scientific evidence now available to us, these basic premises may all be incorrect. Our critics may be right. Developmental experience may have very little to do with most forms of psychopathology, and we have no reason to assume that a careful historical reconstruction of those developmental events will have a therapeutic effect. I know that it is difficult to assimilate this idea; it certainly is for me. Recently, in reviewing a new psychoanalytic textbook on affect, I read, "There is growing consensus that adult psychopathology can be understood with reference to normal child development." I nodded inwardly in agreement, but then I stopped in my tracks and thought about those words more carefully. There is certainly no longer any consensus that schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depressive disorders, or substance abuse can be understood with reference to normal child development. In fact, most research psychopathologists would say that child development explains very little about most so-called Axis 1 disorders. (There is, of course, one very important exception-post-traumatic stress disorder; but the trauma is not crucially related to childhood development.) Psychoanalysts can no longer assert that what they learn about their patient's childhood will help them to explain the etiology of the patient's psychopathology, or even of the patient's sexual orientation.

The task of constructing self-descriptions in psychoanalytic therapy also encounters the problem of memory. Everything we have learned in recent years about memory has emphasized its plasticity, the ease with which it can be distorted, and the difficulties of reaching a hypothetical veridical memory. Much of what psychoanalysis considered infantile amnesia may be a function of the reorganizing brain rather than of the repressing mind. All of this makes the task of constructing meaningful histories of desire in the individual more daunting.

If there is no important connection between childhood events and adult psychopathology, then Freudian theories lose much of their explanatory power. If memory cannot be trusted to construct a self-description, what does one do in therapy?

I no longer ask my patients to lie on a couch and free associate, but I certainly have not given up on face-to-face psychotherapy. My focus is almost entirely on the here and now, on problem-solving, and on helping patients find new strategies and new ways of interacting with the important people in their lives. I still believe that a traditional psychoanalytic experience on the couch is the best way to explore the mysterious otherness of one's self. But I do not think psychoanalysis is an adequate form of treatment. There is certainly no reason for psychoanalysts to withhold medication from their patients. If I can call on Freud, I would suggest that he would have welcomed Prozac, Ativan, and all the rest. Despite his disclaimer, he himself tried to find substances that would relieve human suffering.

Freud's famous conclusion was that, when our patients' neuroses are cured by psychoanalysis, they have to deal with ordinary human suffering on their own. Perhaps it will be no further offense to Freud for me to suggest quite the opposite. When a patient's symptoms are treated, he may then need a psychoanalyst to help him deal with his ordinary human suffering. That is the therapeutic domain in which the art of psychoanalysis will survive.

Alan Stone '50, a graduate of the Boston Psychoanalytic Institute and a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, is Touroff-Glueck professor of law and psychiatry in the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Medicine at Harvard. This article is an abbreviated version of his keynote address to the American Academy of Psychoanalysis.

Additional information:

The original address from which this piece derives

A one-webpage version of this article, suitable for printing out for personal use

For information regarding copyright restrictions, please contact Jim Nourse, Dr. Stone's assistant, at [email protected]

See the letters to the editor for comments on this piece, or to enter your own thoughts.