Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

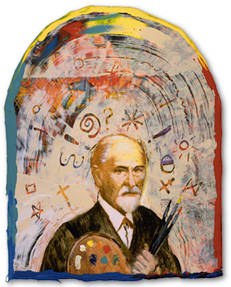

Freud in his later works exemplifies what I have called the noncumulative style in psychoanalysis. Explaining in his brief preface to The Ego and the Id why he had not acknowledged others in the monograph, Freud wrote, "If psychoanalysis [by which he means his own writings] has not hitherto shown its appreciation of certain things, this has never been because it overlooked their achievement or sought to deny their importance, but because it followed a particular path which had not yet led so far. And finally, when it has reached them, things have a different look to it from what they have to others." What he describes is not the collective and cumulative enterprise of science built on the shoulders of those who go before. This is Freud advancing the human project of self-understanding more than any other person in this century-but with the unique subjective vision of the artist and  not through the objective methods of science. Freud did not even feel the need to build with consistency on his own ideas. Kohut's phrase applies as well to Freud as to his followers: the complete psychological works are also a thicket of overlapping, or identical, terms and concepts that neither carry the same meaning nor are "employed as part of the same conceptual context." Scholars like David Rappaport, Heinz Hartmann, Edward Bibring, and Otto Kernberg labored in vain to bring some semblance of order to what I think were flashes of inspired speculation.

not through the objective methods of science. Freud did not even feel the need to build with consistency on his own ideas. Kohut's phrase applies as well to Freud as to his followers: the complete psychological works are also a thicket of overlapping, or identical, terms and concepts that neither carry the same meaning nor are "employed as part of the same conceptual context." Scholars like David Rappaport, Heinz Hartmann, Edward Bibring, and Otto Kernberg labored in vain to bring some semblance of order to what I think were flashes of inspired speculation.

I believe Freud at times recognized that what he was doing was very close to literature. He wrote about creative writers, "One may heave a sigh at the thought that it is vouchsafed to a few with hardly an effort, to salvage from the whirlpool of their emotions the deepest truths, to which we others have to force our way." And again, "Imaginative writers are valuable colleagues. In the knowledge of the human heart they are far ahead of us common folk, because they draw on sources that we have not yet made accessible to science." Clearly Kohut knew this as well. He wrote, "The artist stands, as it were, in proxy for his generation: not only for the general population but even for the scientific investigators of the socio-psychological scene." Freud best described what psychoanalysis is about from this perspective in his paper on his interpretation of Michelangelo's Moses. "Works of art do exercise a powerful effect on me, especially those of literature and sculpture, less often of painting. This has occasioned me, when I have been contemplating such things, to spend a long time before them trying to apprehend them in my own way, i.e. to explain to myself what their effect is due to. Some rationalistic, or perhaps analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me. This has brought me to recognize the apparent paradoxical fact that precisely some of the grandest and most overwhelming creations of art are still unsolved riddles to our understanding. A work of art of this kind needs interpretation, and until I have accomplished that interpretation I cannot come to know why I have been so affected."

Freud managed to see in Anna O, in Elizabeth von R, in the Rat Man, and most importantly in himself the same kind of mystery or riddle he saw in Michelangelo's Moses.

There are, I think, interesting consequences in recognizing-or positing-that Freud was more artist/subjectivist/philosopher than scientist. For one thing, it immediately suggests why it is impossible for us to see farther by standing on his shoulders. It is difficult to imagine anyone claiming that because he stands on Shakespeare's shoulders he can see farther than Shakespeare. Merton Gill, who died in 1994 at age 81, spent his entire life trying to advance Freud's vision, believing that psychoanalysis was a scientific enterprise. In his last book, published in the year of his death, he was forced to acknowledge that psychoanalysis has remained "to a remarkable degree the work of one man, Sigmund Freud." Further on in the book he writes that "systematic research has brought no new 'advances' in psychoanalytic practice or theory," and in a final cri de coeur he echoes Freud's scientific critics, "Let me repeat: We may be satisfied that our field is advancing, but psychoanalysis is the only significant branch of human knowledge (and therapy) that refuses to conform to the demand of Western civilization for some kind of systematic demonstration of its contentions."

Gill steadfastly refused to accept that psychoanalysis was an interpretive discipline rather than a natural science. Plato, Hegel, Kant, Michelangelo, da Vinci, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, and Sartre helped to shape Western civilization and its conception of the human condition without any systematic proofs of their contentions, and so, I suggest, did Freud. I do not think Gill would have taken much comfort from this thought. In his common-sense way he intuited that without its putative scientific roots, psychoanalysis as he knew it would be crippled. That conception of psychoanalysis embodied in the work of Freud held the enterprise together. Even those who disagreed with Freud were anchored and placed in relation to Freud. Now the center does not hold-without the claim of science there is no privileged text.

If psychoanalysis and Freud belong to the arts and humanities, or, as Roy Schafer says, to the hermeneutic disciplines, then that is the domain in which Freud and psychoanalysis will survive. As academic psychology becomes more "scientific" and psychiatry becomes more biological, psychoanalysis is being brushed aside. But it will survive in popular culture, where it has become a kind of psychological common sense, and in every other domain where human beings construct narratives to understand and reflect on the moral adventure of life. One token form of empirical evidence for this proposition: a computer search of Harvard course catalogs for classes whose descriptions mention either Freud or psychoanalysis turned up a list of 40, not counting my own two courses. All of them are in the humanities, particularly literature; no course is being given in the psychology department, and next to nothing is offered in the medical school.

Additional information:

The original address from which this piece derives

A one-webpage version of this article, suitable for printing out for personal use

For information regarding copyright restrictions, please contact Jim Nourse, Dr. Stone's assistant, at [email protected]

See the letters to the editor for comments on this piece, or to enter your own thoughts.