![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

Quarter-Century CelebrationOn October 4, "A Celebration of Women at Harvard College" will mark the anniversary of full coresidence. An intermingling of current students, faculty members, professional women, and alumnae from the class of 1976, the festivities will feature a reception and an array of symposia, including one on women in science, led by professor of biology Colleen Cavanaugh, Ph.D. '85, and another on literature and writing, led by Porter University Professor Helen Vendler, Ph.D. '60. Later in the day, a plaque commemorating the milestone will be unveiled near Canaday Hall at the Yard's newest gate (see September-October 1995, page 73), which has ornamental pickets topped, not with spear points, but with tulips. |

Twenty-five years ago this September, Harvard College officially stopped treating women differently from men. A change it had allowed in increments for half a century reached its logical consummation with the admittance of female freshmen to the dormitories in the Yard.

Of course, the initial breach of Harvard's ivied residential bastions occurred two-and-a-half years earlier, in the spring of 1970, with the integration of the River Houses and the Radcliffe Quadrangle. Late in 1968, the great majority of Harvard and Radcliffe students were found to favor coresidence. That groundswell, and the obvious trend toward coeducation among institutions of higher learning nationwide, led presidents Nathan Pusey and Mary Bunting to give the matter some serious thought.

Bunting had long favored maintaining Radcliffe as a separate college within the University, with its own Houses and deans, much like the colleges at Oxford or Cambridge. But with coresidence now a real possibility, Pusey argued the folly of having women students continue to report to Radcliffe deans while living in the Harvard Houses. That was because--as President A. Lawrence Lowell, A.B. 1877, originally envisioned them in the 1920s--Harvard Houses are not merely large dormitories but active educational units, designed to encourage informal contact among students with different interests and backgrounds and among students and members of the faculty (in the shape of the master and resident tutors). A critical element of Lowell's system was the master's responsibility for the life of the House and the guidance of all its members. It became evident that coresidence was impossible without merger, and thus was born the complex undertaking of combining the undergraduate programs of the two institutions administratively.

In December 1969, while merger talks were still in an early stage, a plan was hatched by professor of psychology Jerome Kagan to permit an interim exchange between Radcliffe's three Houses and three of Harvard's--South House with Adams, North House with Winthrop, and East House with Lowell--the following spring. The exchange was limited to 150 students chosen by lottery. This writer and her best friend from Moors Hall, in North House, put their names in the hat and a few weeks later became pioneering suitemates in Winthrop House.

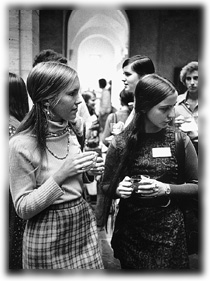

Girls and boys together: Freshman reception at the Fogg, September 1972.E.B. BOATNER |

After the dorm rooms of the Quad, the suite life was a revelation and a joy to most of the women who made the move. So was the proximity to classes and a general sense of being in the center of the action. "I felt very removed when I was living at Radcliffe," says Vickie Charlton '72, a special-education administrator. Interestingly, that isolation suited many of the men who moved to the Quad. Says medical anthropologist Peter Guarnaccia '72, who moved to Jordan J, "Returning to Radcliffe after classes was a real break from the pressure and intensity of the academic part of our lives." Both Charlton and Guarnaccia also express a sentiment shared by many students who came to Harvard from public high schools: they welcomed a restoration of normality in their relations with the opposite gender after the artificiality imposed by segregated dorms. Before coresidence, it was hard for a boy to get to know a girl without first asking her on a date. Now he found himself chewing the fat with her over breakfast, lunch, dinner, and games of hearts.

Coresidence was not to everyone's liking. Some students felt double-crossed, having applied to Harvard and Radcliffe on the basis of what they were in 1968, only to have the very nature of the place shift beneath their feet. Because of the Quad's very intimacy and insularity, coresidence seemed to have a more marked impact there. Students who loved the old Radcliffe worried about protecting their privacy and propriety and about being lost in a huge institution with an administration that was not as accessible or responsive to individual students. "I had no particular desire to attend an all-women's college," recalls Gilah Gelles Goldsmith '72, an attorney. "What I hoped for was the chance to go to a large, prestigious school while still living in a smaller, closer community. The compromise Radcliffe had offered, and which had led me to apply in the first place, was pulled out from under me, leaving me adrift in a Harvard universe I had experienced as cold and even hostile." Goldsmith and a couple of like-minded friends refused to go along with coresidence and were allowed to move to 6 Ash Street, then a dormitory for women graduate students.

For a good many of the men in the Houses, the pleasure of coresidence was unalloyed--except, possibly, for a slightly increased difficulty in concentrating. Indeed, the party-like flavor of those first months of coresidence made studying a trial for the most diligent among us. Things did calm down considerably in the ensuing years, as both men and women began taking each other's nearness for granted. The disillusion rate began to converge with the infatuation rate; an unspoken advisory against in-House romances slowly took hold; reality, as they say, settled in. The undergraduates nowadays have a hard time comprehending what the big deal was in the first place.

For many of the alumni from the classes that preceded coresidence, however, the change was a shock, even an affront. Radcliffe alumnae fretted that their beloved college was selling its soul, while some Harvard men saw coresidence as a sign of the approaching apocalypse. Wrote a member of the class of 1933 in his fiftieth-anniversary class report, "[President] Pusey tore down the scheme set up by the civilised to govern the relations between the sexes....Civilisation is dead, and Harvard's mission is now accomplished."

Even alumni who are less embittered can feel nostalgic for the way things used to be before coresidence, the days of parietals and dressing for dinner. Rika Burnham '72, a museum lecturer, who lived in Cabot Hall, remembers wistfully the women graduating as she was ending her freshman year in the turbulent spring of 1969: "There we were in our tie-dyes and bellbottoms, next to the seniors in their sweater sets, pearls, and engagement rings...Their dreams seemed old-fashioned at the time, but they drew a lot of strength from the community of women at Radcliffe. Only after it was lost did we realize how important that sense of community was." That was a quainter time, when boundaries of all types ruled our lives; in the end, those boundaries seemed to have outlived their relevance. Harvard's changes only mirrored the transformation of society as a whole.

Still, says Harry Lewis, dean of Harvard College, who played a large part in planning this October's commemoration of coresidence, the move in the fall of 1972 toward complete residential integration marked an important moment. "The full inclusion of women in college life at Harvard was inexorable, and housing is central to the educational experience here," Lewis says. "Coresidence opened up to women a crucial part of what has always been a Harvard education."

~ Deborah Smullyan

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()