Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

His triumph secure, Connolly was standing on one leg, pulling on his trousers, when he heard the official band break into the "Star-Spangled Banner." Simultaneously, the crew of the U.S.S. San Francisco, which was anchored in the port of Piraeus, rose as one and stood to attention. The American flag was run up, and Connolly suddenly realized that the national hymn was for him. He, too, stood to attention, as it dawned on him that he was the first Olympic victor in 1,500 years.

As Connolly left the stadium, "floating, not walking, floating across the stadium," he was grabbed by a half-dozen bearded Greeks who kissed him on both cheeks-"guys I had never seen

|

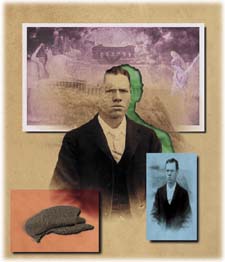

| James B. Connolly was a 27-year-old Harvard freshman when he first heard about the Olympic Games. The American triple-jump champion, he never mentioned the games in his request for a leave of absence, which was denied. In Athens, Connolly created a sensation when he tossed his cap, above, a yard beyond the best previous jump, and then jumped past it. |

Princetonian Robert Garrett won the next event, the discus. Though Garrett had practiced back in New Jersey with an iron disk fashioned to specifications he'd unearthed in classical sources, he had soon given up trying because of the thing's terrible weight. At Athens, he was not entered in the event until the night before, when a Greek competitor showed him a real discus: wood with a brass core and an iron rim, weighing just four-and-a-half pounds. Garrett decided to try it.

The Greek discus throwers were true stylists. Each throw, as they spun and rose from a classical Discobolus stance, was more beautiful than the last. Garrett's first two throws were embarrassingly clumsy. His final throw, however, punctuated with a loud grunt, sent the discus sailing-19 centimeters beyond the best Greek competitor's mark.

Wrote American spectator Burton Holmes, "All were stupefied. The Greeks had been defeated at their own classic exercise. They were overwhelmed by the superior skill and daring of the Americans, to whom they ascribed a supernatural invincibility enabling them to dispense with training and to win at games which they had never before seen." The performances were remarkable. According to Connolly, in five of the track and field events won by Americans, they had not had a single day of outdoor practice since the previous fall.

On the second day of the games, Thomas Burke won the 400- meter race, Garrett won the shot put, Blake took second to an Australian in the 1,500 meters, and Clark competed in the long jump. After fouling on his first two attempts, Clark wondered if he had made the 5,000-mile journey for nothing. He was dependent on being able to mark off his running approach. This is a common practice in which a jumper runs from the takeoff board back down the runway away from the landing pit, marking a footfall once reaching full speed. Then, by starting at that mark and running back toward the sandpit, a consistent performer can ensure a leap that will not break the plane of the takeoff board, yet come within inches of its edge. This practice was and is now allowed under Olympic rules. However, Prince George of Greece, who was officiating at the event, felt that marking runs smacked of professionalism. The Olympic Games were for amateurs. There would be no marking of runs.

"We made a faint attempt to argue," wrote Clark, "were promptly suppressed, and remembering the cautions we had received at home, lest possible international bad feeling should arise out of the games, we meekly bowed" to the prince's decision. Clark's third attempt, however, rendered the dispute irrelevant, as he won with a jump well short of his personal best. Garrett of Princeton took second. The Americans had now struck silver five times in two days. (gold, considered vulgar and ostentatious, was not used for these games, nor was third place officially recognized.)

Cold weather forced Wednesday's gymnastic events over into Thursday. No Americans were entered in any of them. Thursday night the Paine brothers rolled into Athens and found the rest of the American team. After obtaining a certificate attesting to their amateur status, they went straight to bed. The military revolver match at 25 meters would begin at eight o'clock the next morning.

"Early the following morning we went with our six guns and 3,500 cartridges" to what Sumner Paine termed "the prettiest shooting house in the world-200 feet long, built entirely of snow white marble." There, the brothers turned their weapons over for the examination of a committee, and "all went well until they came to the .22 caliber pistols, which they immediately disqualified. The rules said, 'Any pistol of usual caliber.' They ruled that the .22 caliber was not usual." In fact, Sumner noted, it was not usual there. But it meant that the brothers would have to use their Colt .45 revolvers for the match. Their target was a black bull's-eye with a white spot inside it, which in the blinding light, explained Sumner, "gave the same effect to the eye as those trick cards with rings painted on them, which seem to revolve when you look at them closely." Furthermore, "the target was nailed to a gray board, and as our Colt's revolvers were sighted for fifty yards, we had to hold off the target altogether, and the gray background gave no opportunity to pick out some imaginary point to hold on, so it was all guesswork."

"Early the following morning we went with our six guns and 3,500 cartridges" to what Sumner Paine termed "the prettiest shooting house in the world-200 feet long, built entirely of snow white marble." There, the brothers turned their weapons over for the examination of a committee, and "all went well until they came to the .22 caliber pistols, which they immediately disqualified. The rules said, 'Any pistol of usual caliber.' They ruled that the .22 caliber was not usual." In fact, Sumner noted, it was not usual there. But it meant that the brothers would have to use their Colt .45 revolvers for the match. Their target was a black bull's-eye with a white spot inside it, which in the blinding light, explained Sumner, "gave the same effect to the eye as those trick cards with rings painted on them, which seem to revolve when you look at them closely." Furthermore, "the target was nailed to a gray board, and as our Colt's revolvers were sighted for fifty yards, we had to hold off the target altogether, and the gray background gave no opportunity to pick out some imaginary point to hold on, so it was all guesswork."

The match was not even close. John Paine won with a score of 442. Sumner took second with 380. The next best man scored below 200. The next day, by prior agreement between the brothers, the first day's winner sat out. Sumner contested the choice revolver at 30 meters as the sole American entry. Again, the match was not close, and Sumner won by the same score his brother had achieved the previous day.

An interesting phenomenon of this second day was the flattery by imitation showered on the American marksmen. Wrote Sumner, "The Greeks having seen us do several little tricks that were new to them on the first day, endeavored to benefit themselves by some of them on the second." Describing the same incident, spectator Holmes mentions one of the Paines' tricks: taking frequent sips of whiskey from pocket flasks at critical moments in the shooting. "On the second day, not a Greek contestant sighted a gun, without first applying a black bottle to his lips," reported Holmes. This was probably the first case of widespread drug use in the modern Olympic Games, though it seems not to have been against the rules. On the same day as the first shooting match, accusations circulated that the French distance runner Lermusiaux was sipping brandy before the marathon. What was permissible for marksmen was apparently not okay for endurance athletes.

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Harvard Magazine · 7 Ware Street · Cambridge, MA 02138 · Phone (617) 495-5746