Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

At last the three undergraduates were free from their studies and could join the other B.A.A. team members: distance runner Charles Arthur Blake, class of 1893; sprinter Thomas Burke '01, who enrolled at Harvard only after his Olympic experience; high hurdler Thomas Curtis, a Columbia College and MIT man; marksman John B. Paine, class of 1891, and his brother and fellow marksman Sumner Paine, class of 1890. With Clark high jumping and long jumping and Hoyt pole vaulting, they had the makings of a formidable team. Triple jumper Connolly traveled in their company as sole representative of the Suffolk A.C., along with coach and B.A.A. trainer John Graham, formerly a janitor/trainer at Harvard's Hemenway gymnasium; he later became Harvard's track coach (1900-1905).

|

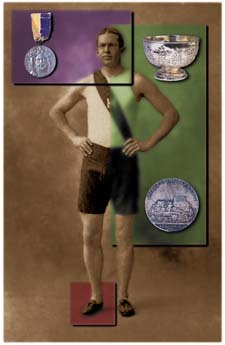

| Ellery H. Clark '96 was the only Harvard undergraduate who obtained permission to attend the first Olympic Games. He won the two first place silver medals, shown obverse and reverse above, in the high jump and the long jump. Greek Crown Prince Constantine conferred the silver cup on double winners. |

The last of March I came home to luncheon one day and found my brother, Lieutenant J. B. Paine, sitting in my office. I had not the slightest idea that he was on this side of the pond."When does the next train start for Athens?" said he.

"I don't know," said I.

"Well," said he, "find out, and get your revolvers and we will go there, for the Boston Athletic Association (of which we are both members) has sent a team over, and as there are two revolver matches we may be able to help out the Americans."

"We were unable to find out the conditions of the matches," Paine continued, "except that the target revolver match was at 30 meters." Sumner spent the afternoon at a gallery "experimenting with nitro powder to get a load that shot well at that distance." He finally settled on "21 centigrammes of powder, with a round bullet cast by the well-known firm of George R. Russell & Co., of Boston." Said he, "I did not care to trust the French bullets, with their long screw tails, in such an important match."

Uncertainty about the weapons required and the number of rounds necessary in the matches led the Paines to pack an arsenal: two Colt army revolvers, two Smith & Wesson Russian model revolvers, a Stevens .22 caliber pistol, a Wurfflein, two pocket weapons, and 3,500 rounds of ammunition. Ninety-six shots were all they needed to win at Athens.

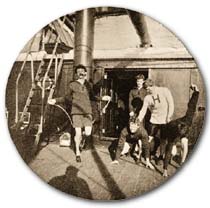

Meanwhile, the rest of the American team had boarded the tramp steamer Fulda for the trip to Naples, Italy. The group was made up of Connolly, four Princeton undergraduates, a swimmer named Gardiner Williams, and the five remaining B.A.A. athletes, plus their coach. Conditioning on board ship was a primary concern for the athletes. But the captain, wrote Clark in his Reminiscences of an Athlete, "after a single glance at our spiked shoes, promptly forbade their use upon his much-prized decks; yet rubber soled gymnasium shoes did nearly as well, and every afternoon we put on our running clothes, and practised sprinting, hurdling, and jumping on the lower deck." The Princetonians practiced twice daily, the Bostonians just once. Connolly, who was nursing a back injury sustained in Hemenway Gymnasium two afternoons before sailing, relaxed in a deck chair the whole voyage, "just sitting there and looking out on the blue sea through the open rails. It was swell," he reported. Clark marveled at the action of the pitching and rolling vessel on his high-jumping attempts. "It all depended on whether you left the deck at the moment when the vessel was bound up or down. If the former, about two feet was the limit you might attain; if the latter, there came the glorious sensation of flying through space; a world's record appeared to be surpassed with ease; and one's only fear was of overstaying one's time in the air, and landing, not on the decks again, but in the furrow of the wake astern."

On March 30 the ship reached Gibraltar, and Connolly rose from his deck chair "with every pain and ache gone and me feeling loose as ashes." The team got in its first (and last) real workout at a track outside town. Afterwards, when they had all settled into carriages for a drive around town, Arthur Blake elected to run behind. He was the B.A.A.'s distance man, earnestly training for the marathon. Yet Blake knew how to take his medicine. Whenever he passed a group of young boys, he would "stoop and pretend to pick coins from the dust behind the carriages, shouting delightedly the while. The small boys were easy victims...and Blake, pursued by the barefooted hunt, came gloriously along in our rear...," reported Clark.

At Naples, the team switched to rail transport for Brindisi. Connolly lost his wallet to a pickpocket, and nearly missed the train as a result. Arriving without further mishap at Brindisi, the Americans took a boat to Patras, and from there a train to Athens, where they arrived on Sunday, April 5.

"Our welcome was magnificent," wrote Clark. "There were speeches--cordial we had no doubt; lengthy, we were certain." A bacchic celebration ensued, at which the exhausted and normally abstemious Americans drank only to defend the honor of their country, they later claimed. The team slept little that night, and were awakened early the next morning by a raucous parade. Banners were streaming from windows all over the city. A mix-up over the 12 days' difference between the Greek (Julian) and Western (Gregorian) calendars meant there would be no time for practice or acclimation to their surroundings. This was the opening day of the Olympic Games.

"Slowly the magnitude of the whole affair began to dawn upon us," wrote Clark. "Up to this very moment we had no slightest idea of what the games meant to Greece; we did not know whether the huge Stadium would contain a thousand spectators or ten thousand." But then, "through the streaming crowds we

|

| Skip rope aboard the tramp steamer Fulda. Blake, Curtis, Hoyt, Clark, and Burke ham it up for the camera. |

In rapid-fire succession, officials started three heats of the 100-meter trials. This was an important event. In classical times the four-year interval, or olympiad, between games had been named for the winner of the 100-meter race. These trials also marked the American introduction at an international meet of the "crouch" start that eventually led to the use of starting blocks. Three Americans dominated their heats, qualifying for the finals: Tom Curtis and Tom Burke of the B.A.A., and Francis Lane of Princeton. Their teammates' delighted shouts of "B. A. A.! Rah! Rah! Rah!" at first startled the predominantly Greek crowd, which had never heard organized cheering before, "but all at once they seemed to grasp the meaning of our effort," wrote Clark. "We had, by good fortune, chanced to please the popular taste, and the cheer from that moment until we left Athens was in constant demand."

Next up was the triple jump, James Connolly's forte. There were no trials; three jumps would determine the winner. Connolly's turn came last. He walked out to the sandpit after the other jumpers had finished, removed his cap, and tossed it to the ground a yard beyond the best jump. The astonished crowd now watched intently as he breathed on his hands (the next day's papers reported that he had uttered a prayer), then wiped his jersey preparatory to his run. Then he bounded down the runway and hopped, hopped, and jumped beyond the cap. "The spectators sprang up shouting, 'It's a miracle! A miracle!'" according to Mandell, who characterizes Connolly's throwing down the cap as "at once arrogant and joking." Despite the poor conditions, which included a soft, fresh-laid runway in which competitors' heels sank two inches, a gray chilly day, and a headwind, Connolly had every reason to believe that he would win. His winning jump of 45 feet was considerably shorter than his previous records, and far less than the 49-foot world record mark he set later that year in New York.

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Harvard Magazine · 7 Ware Street · Cambridge, MA 02138 · Phone (617) 495-5746