Graduate-student organizers were buoyed last summer after the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) granted students who do paid teaching and research at private universities the right to unionize. Soon after, union elections were scheduled at Harvard and Columbia, where students had been organizing to unionize and bargain for improved conditions like affordable family health care, child care, and on-time pay. Now, nearly two months after Harvard’s election, a final outcome, and potential path to unionization, still appear remote.

After more than a month of delay, the results of the balloting in November were inconclusive: 1,456 students had voted against a union while 1,272 voted in favor—but that margin is smaller than the number of ballots (314) that remain under challenge because the University and student organizers disagree over whether they were cast by eligible voters. To resolve the challenges, the NLRB will begin hearings on February 21, a process that could delay the final outcome indefinitely.

Making matters more complicated, both Harvard and graduate-student union organizers filed objections to the election soon after the tally was released. (This is not uncommon in union elections; the NLRB gives parties a short window to file objections after a vote count.) The University’s objection concerns just one ballot, which had voted “no” to unionizing. The NLRB did not count it because it had writing on it (“Hello counter! Have a good day :)”).

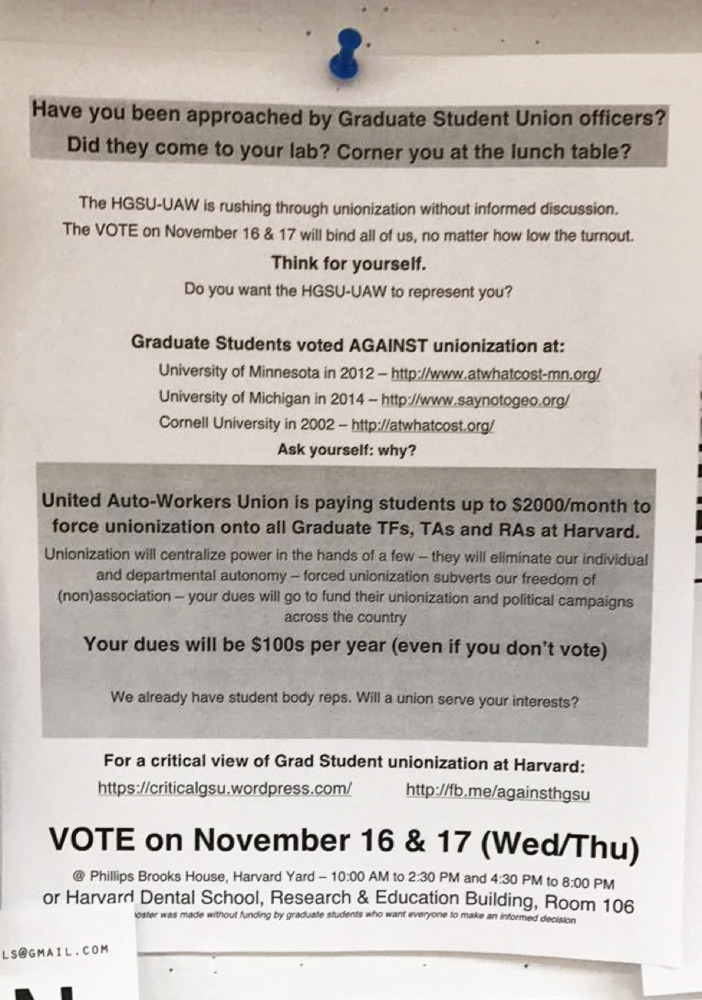

An anti-union poster hangs in the Science Center in the days before the unionization election

Courtesy of Harvard Magazine

The union’s objection is much wider in scope: it alleges that Harvard’s voter list had excluded many eligible voters, and that its reliance on students’ preferred rather than legal names created further confusion, because students had to present identification at polling places. “As many saw at the polls during the election, Harvard failed to provide an accurate list. Hundreds of student workers were left off the eligible voter list provided by the employer to the NLRB in advance of the election, leading to confusion about who was eligible to vote,” the Harvard Graduate Student Union-United Auto Workers (HGSU-UAW) wrote in a statement. “This omission of such a large number of potential voters—a substantially larger number than the margin of the preliminary vote count—prevented a fair, democratic election.” If the NLRB agrees with the objection, it could invalidate the election, resulting in a new one—perhaps the outcome the union seeks, given the 184-vote margin against unionization in the reported tally from the November balloting.

That outcome might appear surprising, given the union’s diligent organizing leading up to the election, and for more than a year before it. But opposition to unionization, loosely organized into a student coalition called “Against HGSU-UAW,” became publicly vocal in the weeks before the election. Anti-union organizers were united by concerns over a union’s ability to represent Harvard’s many departments; opposition to paying union dues, which students fear could cost more than what they gain in benefits; opposition to UAW’s political activities nationally; and anti-union sentiment generally. Some have argued that the chief economic weapon for unions—the threat of a strike—wouldn’t be credible because Harvard graduate students would likely be unwilling to abandon their research.

At Columbia, where students voted by an overwhelming margin in favor of unionizing, the administration has filed objections to the outcome, alleging that student organizers had engaged in voter intimidation. Yale’s unionization effort remains mired in protracted legal battles. Several times in the past, the NLRB has reversed its position on university students’ organizing rights, provoking student organizers’ fears that a reconstituted NLRB under President-elect Donald Trump could do so again.