For the third year in a row, Harvard reported a modest budget surplus, expressing cautious optimism about its future financial performance. Operating revenue for fiscal year 2016 exceeded operating expenses by $77 million, up from last year’s surplus of $62 million, according to its annual financial report, released today. Operating revenue went up 5.6 percent from last year, to $4.78 billion, while operating expenses increased slightly less, by 5.3 percent, to $4.7 billion. Strong contributions from the capital campaign, tuition growth, and increases in both private and public research funding contributed to this year’s performance.

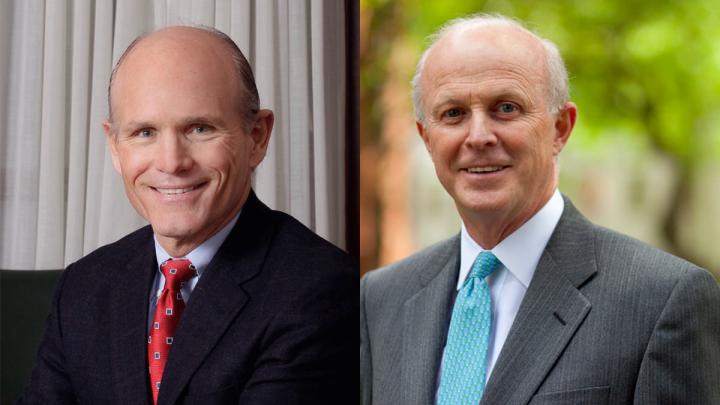

Distributions from the endowment, or the endowment income that’s made available for University operations, continue to make up the single largest source of operating revenue. Distributions increased 7 percent from last year, to $1.7 billion. “It is hard to overstate the importance of philanthropy to the University,” vice president for finance Thomas J. Hollister and University treasurer Paul J. Finnegan wrote in the report. “Thanks to the generosity of past donors, endowment distributions this year made up our largest source of operating revenues at 36% of the total.” And capital campaign gifts contributed significantly to basic operating expenses: current-use gifts—donations that fund the University’s current operations, rather than future projects—accounted for 9 percent of revenue. Overall, current-use gifts have increased 45 percent since the start of the Harvard Campaign, and gifts for the endowment and specific building projects have increased 130 percent.

One of the University’s greatest financial concerns is declining federal support for basic research. For the first time in five years, federal funding to the University increased slightly, to $597 million, up from $578 million last year. This is still much less federal aid than Harvard received a few years ago, and it represents a small fluctuation rather than a systematic shift in funding. Government funds appear constrained indefinitely, the report stresses, making the University increasingly dependent on private research funding. Non-federal grants—from foundations, corporations, and individuals—increased by 9 percent this year, to $248 million, accounting for nearly a third of sponsored-research funding. Another growing source of revenue, in keeping with the University’s increasing reliance on private-sector funding, is commercialization of intellectual property: “We have seen rapid growth in revenue from royalties and license fees from life sciences research, technology transfer, and publishing,” Hollister said in an interview with the Harvard Gazette.

Revenue from tuition increased by a sizable 7 percent this year, to $998 million. This was driven largely by continuing- and executive-education programs at Harvard Extension School and the professional schools, particularly Harvard Business School. Revenue from these programs was up 10 percent this year. Revenue after financial aid from graduate tuition was up 6 percent, and revenue from undergraduate tuition continues to grow modestly, at 4 percent this year, because of Harvard’s significant commitments to financial aid.

Despite these gains, the University’s net assets declined overall by 5 percent this year, from $44.6 billion to $42.4 billion, owing to significant losses to its endowment “In most years, and over time, investment gains from the endowment generally outweigh distributions,” Hollister and Finnegan wrote. “The investment losses in 2016 reflect a 2% negative investment return during the year...It was a very difficult investment year for all endowments and pensions, the worst since the 2008-09 financial crisis.” The University reported last month that the endowment declined by $1.9 billion in fiscal year 2016, or 5.1 percent of its value. (Not just Harvard, but about three-quarters of the colleges that have reported, have suffered losses to their endowments this year.)

Investment performance is likely to rebound in future years, but University officials stress that the future still look uncertain: “[M]ost financial experts agree that investment results for endowments will be modest due to low interest rates, low risk premiums and muted worldwide economic growth,” the report notes. University president Drew Faust, in a letter prefacing the report, stressed this message: “American higher education is entering an era of constrained financial circumstances. Colleges and universities across the country are facing challenging endowment returns and intense pressure on both federal research funding and tuition revenue.”

On the expense side, employee salaries and benefits make up by far the University’s largest expenditure, at $2.3 billion, or 50 percent of operating costs. Salaries increased by 6 percent, to $1.8 billion, due to routine raises as well as new hires. Benefits were also up 6 percent, to $530 million. Controlling the growth of the cost of benefits, particularly health insurance, continues to be important to managing Harvard’s expenses overall (“health benefits are the most challenging expense category” for every employer, Hollister told the Gazette). One strategy that the University has pursued in the last few years has been to add more cost-sharing to health plans, including deductibles and higher copayments, but doing so remains challenging because faculty and staff often oppose it. Just last month, the dining hall workers’ union went on strike in part over a proposal to increase copayments in its health plan. Under the final contract agreement, the workers will be allowed to keep their current plan for another two years, a compromise for both sides.

The fruits of the capital campaign are visible everywhere on Harvard’s campus—from the undergraduate Houses, which are undergoing renovation for the first time in nearly a century, to the recently opened Chao Center at the business school. But the future of universities’ traditional revenue sources, the report stresses—tuition, government funding, and endowment income—remains tenuous.