Bend, a solo performance by theater artist and puppeteer Kimi Maeda, tells the story of her father, who crossed paths as a boy with the sculptor Isamu Noguchi at a Japanese-American internment camp during World War II. (Robert Maeda later became an Asian art history professor at Brandeis, focusing much of his research on Noguchi, who had volunteered to be interned.) On stage, Maeda creates images with wooden blocks and drawings in sand that are projected, along with 1940s archival footage, on a large screen behind her. She also uses artifacts, like a leather suitcase from which sand pours, as if in an hourglass, as she walks, and plays audio clips of wartime news reports and personal narratives spoken by her and her father, who now has dementia. Her artful animation of a painful slice of American history and its effects on both men is a meditation on loss, identity, and the fluidity of memories.

For Roxanna Myhrum ’05, artistic director of the Puppet Showplace Theater, in Brookline, Massachusetts, where Bend plays in February, artists like Maeda are using the ancient art form “to explore profound humanistic questions.” Many people think of puppetry as “dolly-waggling,” she adds, “which is what we in the biz call bad puppetry: ‘Oh, I’ve got a puppet on my hand. I’m going to wave it around and put on a show.’” What excites Myhrum, also president of the Puppeteers of America, is how the theater encompasses everything from sock puppets, Muppets, and marionettes to passionate amateur acts during “Puppet Slams” and more conceptual pieces like Bend “that push the boundaries of visual and object theater.”

A native of Springfield, Massachusetts, Myhrum began acting lessons locally at The Drama Studio in third grade, then discovered puppetry. At 15, she had a “mind-blowing experience: telling the story of the universe and of Chinese totalitarianism—with puppets” as the youngest person chosen to work on Hua Hua Zhang’s The Bell, based on mythological Chinese characters, at the National Puppetry Conference at the Eugene O’Neill Theater in New London, Connecticut. Myhrum also directs and produces opera and theater and has worked as a puppetry director or coach at almost all of Boston’s regional companies, in addition to serving as resident stage director of the Lowell House Opera.

Roxanna Myhrum with the unflappable star of Robin Hood

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Her role at the Brookline Village nonprofit, she says, is like running a church-cum-start up: “Our theater is a cathedral of joy and wonder—and the audience is our congregation,” and yet “so much has changed economically for puppeteers, and we are in danger of losing this unique art form. It’s a huge priority for us to recruit new talent and support innovation and experimentation.” The theater was founded in 1974 by the late Mary Putnam Churchill ’52, who first began using puppets to engage students when she was a reading tutor. During 23 years she built the organization from a few weekend shows to an internationally recognized puppetry center; there are only a handful like it in the country.

A cozy space, it seats 95 and offers more than 300 shows annually, along with educational programs in schools, a summer youth camp, and year-round classes and workshops like “Introduction to Shadow Puppetry” and “Furry Monsters 101” for adults. In 2013 Myhrum reconfigured the theater’s incubator program to support new works by local emerging artists, and has since premiered six new shows. Resident artist Brad Shur also gives about 60 performances a year and has eight original shows in his repertoire, including January’s interactive Cardboard Explosion!

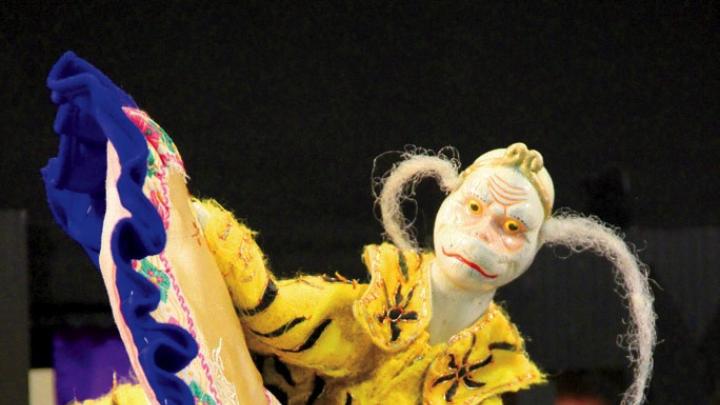

But the majority of performances at the theater are by outside artists—local, national, and international—and are geared to younger audiences. Bonnie Duncan often combines puppetry, dance, and acrobatics in original works like Squirrel Stole My Underpants (about a girl’s imaginary journey to reclaim a beloved article of clothing), to be performed on November 27-29. The holiday season also brings Margaret Moody’s The Monkey King (December 10-13) and the National Marionette Theatre’s Peter and the Wolf (December 31-January 3) “We are often children’s first exposure to live theater,” says Myhrum. It’s electronic-free and often interactive, thereby stimulating imaginations, role-playing, and the practice of storytelling, she adds. For Susan Linn, Ed.M. ’75, Ed.D. ’90, a ventriloquist, children’s entertainer, and pioneer in the use of puppets in psychotherapy, the theater (where she has also performed) is a critical forum for children and adults to “experience human creativity, firsthand,” free of the onslaught of commercialism and technology. “Puppeteers are swimming against a cultural tide,” adds Linn, who also founded the nonprofit Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood. “So many children are immersed in the mainstream culture that’s basically run by three or four companies like Disney, Nickelodeon, and Fox...Frozen was a good movie, but then there is Frozen everything: video, apps, video games, zillions of toys. And so that creates an unfortunate norm for what people think children need in order to enjoy themselves. The puppet theater is a whole different experience.”

At a recent performance of The Swan, an original, wordless work by Quebec’s Théâtre de Deux Mains, puppeteer Louis-Philippe Paulhus played all the parts amid an intimate stage set with handmade trees and a pond (in fact, a monitor that changed colors) inspired by a Tiffany glass window. After the show he answered questions from the preschool audience. “Was the water real?” “What is the bird doing now?” “How do they talk?” To that, Paulhus gently answered, “When I make the mouth move, I have to make the sound at the same time.”

Like many puppets, the swan emitted not words but raw vocalizations that reverberated emotionally. That ability to engage in nonverbal communication, says Myhrum (who, like all serious puppeteers, had to learn the art of speaking gibberish) makes puppetry especially accessible to children and useful in therapeutic contexts and cross-cultural communications. The art form is more akin to dance and pantomime than to traditional theater, she adds, because it readily conveys universal experiences: “Psychologically, puppetry demands an engaged audience. When a puppeteer is doing her job, an inanimate figure will activate our hearts, minds, and imaginations. It’s the audience’s job to bring the character to life.” As they process what’s going on, attendees are drawn into perceiving action on a metaphoric level, using their “puppetry sense,” she says: “a sensory capacity that is different from the verbal language of human actors’ theater.”

The intimate setting and often miniature scale of the productions—from the portable stage set to the cast of pint-sized “actors”—signify “small and vulnerable,” according to Myhrum. “Puppet shows trigger the part of us that says, ‘Care for pets, care for small animals.’” On the flip side, “characters can also be over-the-top, invincible,” she says. They can even be subversive or negative, hence the common use of puppets to engage in taboo subjects and political satire, or as a way to help those suffering from illnesses or as victims of trauma voice their experiences. Linn calls puppets “a valuable tool for expression because they are simultaneously ‘me and not me’”: puppets are like “a psychological screen. We don’t have to take responsibility for what we make them say—for that reason they are incredibly disinhibiting.” Puppets, Myhrum asserts, “can say and do things that human actors [and audiences] wouldn’t dare. That’s what makes them so powerful.”

And not just for kids. Although caregivers can and do enjoy shows with simple themes, the theater’s “Puppets at Night” events, like Bend, are strictly for adults. The bimonthly Puppet Slams (the next falls on January 16) offer a wide range of acts, including a bloody trip to the dentist. The theater began the slams in 1996; the movement has since expanded across the country and is financially supported by the Puppet Slam Network, founded by Heather Henson, daughter of the Muppets’ creators Jim and Jane Henson.

The Muppet Show and Sesame Street were a popular catalyst for the development of American puppetry in recent decades. But the art of animating inanimate objects has ancient origins across the globe, and at one time was restricted to a culture’s healers and religious figures. “There is always something profoundly sacred about the puppet, dwelling as it does on that indefinite border between life and its absence,” curator Leslee Asch, a former executive director of the Jim Henson Foundation and now head of the Silvermine Arts Center in Connecticut, wrote for the Katonah Museum’s 2010 exhibit, The Art of Contemporary Puppet Theater. “Puppetry serves as an extraordinarily powerful means of giving form to the internal or invisible.” The willing suspension of disbelief, Asch continued, allows the audience to engage and accept that the created actors are “real.” Puppetry is so often relegated to children’s entertainment, she laments, because “sadly, in our society only children have been allowed to maintain the capacity for wonder, awe, and fantasy.”

Myhrum agrees. Puppetry’s “magic” is seducing an audience into identifying with characters composed of papier mâché, cardboard, cloth, plastic, wood, or clay. In 2014 the theater premiered the adult show Reverse Cascade, by Anna Fitzgerald, a wordless story about circus performer Judy Finelli’s struggle with multiple sclerosis. Several black-clad, nearly invisible puppeteers create “Finelli,” the only character in the play, by tying together four silk scarves (the type jugglers use). The audience sees “her” miraculous circus tricks, the scarves moving in graceful arcs and dance steps, before her lithe body starts to fail—terribly. Cello music plays, the artist flails and flops, trying to gain control of her body, which is fragile because it’s composed of scarves. Through a slow and painful process she manages to pull herself up to balance on aerial circus rings, but soon those rings become the wheels of her wheelchair. “The audience sees that this woman has knots in her leg because she has knots in her leg—the abstraction becomes real,” Myhrum notes. “A puppet is a visual metaphor for a human struggle that takes place on this little tabletop stage.”