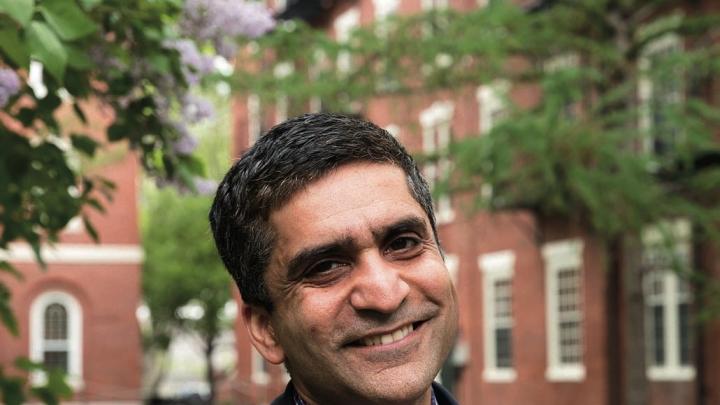

In his book-lined office in University Hall, Rakesh Khurana keeps handy a well-worn copy of Samuel Atkins Eliot’s 1848 A Sketch of the History of Harvard College and of Its Present State. The slender, red volume arrived in the mail last summer, an anonymous gift for the newly minted dean, who took the helm of the College in July 2014.

Pulling it off the shelf this spring, Khurana, the first Danoff Dean of Harvard College, opens to a yellow Post-It flag, and reads aloud the description of the seventeenth-century gift that funds the Detur Book Prize, the College’s oldest honor. The gift, he quotes, was for the purpose of “breeding up hopeful youth in the way of learning…for the public service of the country in future times.” That, Khurana reflects, remains the mission of Harvard College: “It was to educate—and it is to educate—the citizens and citizen leaders for our society.”

A year into his new role, the Bowser professor of leadership development says he sees himself as a “steward” of that mission—to remind students, faculty members, and the College community of Harvard’s nearly 400-year-old liberal-arts core. For Khurana, a Harvard education should expose students to new ideas and new ways of thinking—a contrast to preprofessional training that “might prepare you for a job, but I’m not sure necessarily prepares you for a career, or necessarily prepares you for life.”

A graduate of the University’s Ph.D. program in organizational behavior, Khurana has spent the past decade and a half across the river at Harvard Business School (HBS). His years in a professional school, in fact, helped convince him of the power of a liberal-arts education. As an example, he describes how students from preprofessional and liberal-arts backgrounds tackled case-study discussions, which often dealt with tricky questions of leadership and management. Over the years, he saw a “vast difference” in students’ abilities “to think about problems creatively, to locate a situation in a cultural context—to see the economics of that situation, but also the anthropology and the sociology,” he explains. Even when based at HBS, therefore, Khurana kept the undergraduate experience close at hand: he served as a nonresident tutor in Eliot House while in graduate school, and he and his wife, Stephanie, became master and co-master of Cabot House in 2010.

But the new dean’s focus comes at a time of relative tumult for that liberal-arts philosophy, both across the landscape of higher education and closer to home. National discussions of education quality have increasingly focused on “return on investment”—weighing tuition paid and time spent against potential future earnings. By necessity, this has increased attention to skills-based learning, which has not always fit easily into the Harvard curriculum. At the other extreme, critics have questioned whether schools like Harvard live up to their purported “liberal-arts” goals. The month after Khurana moved into his decanal office, a cover story in The New Republic—illustrated with a bright red Harvard flag, going up in flames—implored: “Don’t Send Your Kid to the Ivy League.” Writer William Deresiewicz argued that places like Harvard and Yale, where he taught English for 10 years, attracted and produced students who, though smart and driven, were afraid of the potential failure that comes with true intellectual engagement.

Khurana’s vision for the deanship—as a locus of conversations revisiting the very core values of a Harvard education—marks the start of a new chapter in University Hall. In the spring of 2013, then-dean Evelynn M. Hammonds, Rosenkrantz professor of the history of science and of African and African American studies, stepped down from her position, amid concerns over her involvement in searches of College staff members’ e-mail accounts.After Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean Michael D. Smith named him to the position in January 2014, Khurana embarked on a six-month study of his new role, meeting with faculty, students, and staff to hear their visions for a Harvard education. In these conversations, he says, “People were sometimes too worried about seeing the College as a stepping stone to something else, rather than a place itself.”

In his first year as dean, Khurana has emphasized making a strong, proactive case for the value-added of a College education: “to give people a meaningful life, a sense of introspection, a sense of what civic duty is”—in other words, to cultivate those “citizens and citizen leaders.” Until recently, the College dean’s office—popularly associated with students’ House, extracurricular, and social lives—has not been seen as driving this kind of discourse. Khurana, therefore, has become a present dean, quietly bringing up questions of values and reflection in his everyday interactions across campus. His active Instagram feed chronicles formal meetings as well as selfies taken with students at events like Yardfest and basketball games. There are deeper messages, too. In November, for example, he posted a 15-year-old rejection letter from a prestigious academic journal, accompanied by a piece of advice his wife gave him at the time. This same balance of confidence, introspection, and humility comes through in private conversations and public remarks. Self-deprecatingly, he likes to remind students that the College rejected him.

His role in the review of the General Education program, a five-year-old system of requirements for College students, exemplifies the link he sees between the intellectual and personal transformations central to the Harvard experience (see “Tough Grading for Gen Ed,” in this issue). In April, shortly before the release of the Gen Ed review committee’s relatively harsh five-year report, Khurana and dean of undergraduate education Jay Harris held the first of a series of faculty town-hall meetings to discuss the College curriculum. What he heard there, he says, was a “consensus”: that the College should help students develop a system for intellectual engagement, and that more meaningful interactions between faculty members and students is the best way to do so. Both groups have recalled such meetings—in which faculty members shared their stories, and students found mentors—as central to their Harvard experience. “My role is WD-40,” Khurana says: helping facilitate these interactions and thereby break down those divisions to create one College community.

Khurana defines Harvard by a sense of restlessness, constantly striving to be the best. “I think Gen Ed also says excellence for what. It’s excellence for educating citizens and citizen leaders for a changing world,” he reflects. “It’s very exciting that the faculty are feeling a sense of responsibility and agency and, I think, a sense of urgency to get this right.”

And as the world has changed, so too, he says, have the obstacles that stand in the way of getting it right: “The challenges of our society don’t stop at the gates of Harvard.” The College is more racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse than ever. Long gone, for good reason, are the days when the liberal arts meant teaching a curriculum of white, male prep-school graduates a curriculum of white, male writers. Khurana sees himself as someone who likes to “discuss what I think is undiscussable”—including how issues of class, access, and success manifest themselves on Harvard’s campus. One growing problem, he says, is that students often arrive with a K-12 education that, because of high-stakes testing, has focused on teaching skills—not necessarily how to think.

For Khurana, a key part of fostering personal and intellectual transformations, therefore, is opening spaces for students to stop, take a step back, and think about the changes happening around and within them. He has joined with other College administrators in strengthening and expanding programs to encourage reflection among undergraduates. In an experiment last fall, he helped develop a curriculum of readings and conversations for freshman orientation that centered on the value of a liberal arts and sciences education. “Sometimes students are—obviously, in a good way—so taken by the name Harvard, they may not know as much as we would like about the undergraduate program itself, and what its purpose and its construction are,” he explains. “We have to do a better job on communicating that.”

This year, he and dean of freshmen Thomas A. Dingman helped initiate a mid-year gathering that brought together the entire freshman class. Following a comedy show, a spoken-word performance, and other entertainment, Khurana took the stage last at January’s “ReFRESHMENt” event. He began, he explained to the crowd in Sanders Theatre, “where I start every discussion, which is the mission of the College.” He spoke of “citizens and citizen leaders,” as well as the liberal arts’ “transformative power”—reiterating the mission he’d first shared with the Class of 2018 at September’s Convocation. But Khurana also added new advice, the kind that anxious college freshmen most need to allow transformation to take hold. “There’s no one best way to do Harvard,” he reminded them. Ending the evening, the dean—halfway through his own freshman year—dismissed the class with “Thank you. See you guys in the dining hall.”