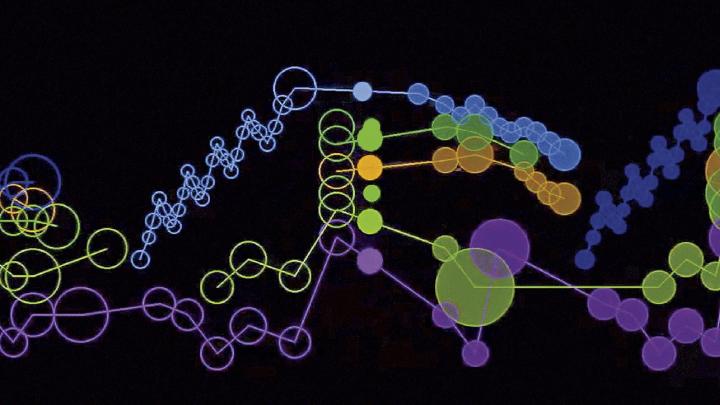

What do we see when we listen to music? In 1940, Walt Disney’s Fantasia famously drew Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite as dancing flowers, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring as a T-rex on the rampage. Today, the music-library software preinstalled on most personal computers offers customizable options: flames, puddles of color, wheeling galaxies. Although these interpretations have artistry, they neither promise nor grant real understanding of how music works. Coasting atop the waves of sound, the images reflect little of its actual structure. But what if a tool were designed to put sight squarely in the service of sound?

“It seems that the twenty-first century is really the right time to think about animated music analysis,” says Peabody professor of music Alexander Rehding. An array of recently developed digital tools, used by musicians and laypeople alike, suggests new possibilities for researchers keen to map aural realms by visual means. Soundslice, for example, offers interactive sheet music that guides the learner through a score by integrating written notation with a sound file; SoundCloud presents a time-slider and the outline of a sound wave to orient a listener within the music, and also displays listener comments keyed to specific moments in a piece. Now, Rehding and his collaborator, Jones professor of African American music Ingrid Monson, are developing a Web application that will depict the insights of music theory, syncing an animated analysis with a sound file. “The twenty-first century is really the right time to think about animated music analysis.”

The application visually traces a piece’s progression through what’s known as “tonal space,” which encompasses chord transformations, intervals between pitches, and the relations between keys. Nineteenth-century theorists represented this aspect of music in a two-dimensional format: a grid with an x and y axis. As the structural understanding of music advanced, the shape of tonal space also evolved in complexity—into a cylinder, then a spiral within a cylinder—before finally reaching the current model, which Rehding describes as “a doughnut that’s also a Möbius strip.”

In creating what he calls “the quite technical interpretation of how music works and how it hangs together, we use a lot of diagrams,” Rehding explains. The academic community already shares the structure of a symphony, or a jazz pianist’s chord transformations, through dense illustrations. But when used to communicate with even a slightly wider audience, these diagrams can confuse as often as they clarify. Even the most gung-ho undergraduates become bewildered when talked through these analyses, which are challenging to reconcile with the music itself. And there’s another problem, Rehding adds: “If you try to show how the flow of the music works, then the static medium of print isn’t well-suited to a lot of the things that go on.” By contrast, a dynamic diagram can situate the listener in time; a computer model can display change in a third dimension, even rotating as necessary.

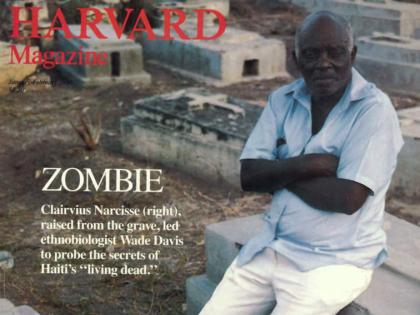

The two ethnomusicologists study vastly different repertoires: Rehding focuses on nineteenth-century Germany; Monson works on jazz and the African diaspora. In her field, visual representation is a particularly fraught topic—many debate whether music that’s composed during in-the-moment performance, as jazz improvisation is, should be transcribed into Western notation at all.

“We’re both interested in the sensory experience of listening, and view it as a kind of knowledge that’s not necessarily text-based,” Monson explained in August to the DARTH (Digital Arts and Humanities) Crimson group at Harvard. Digital tools could allow scholars to legibly depict their aural observations, while bypassing the score tradition. Expressing musical structures through new visualizations could also cut across the cultural biases and natural barriers presented by standard notation.

Chatting before a fortepiano concert at Jordan Hall in February 2014, the pair discussed a graduate seminar Monson was attending on new techniques of musical analysis. Intrigued by the idea of bringing theory’s insights into the digital age, they set their project in motion by reaching out to colleagues knowledgeable about computer applications, including Michael Cuthbert ’98, Ph.D. ’06, an associate professor at MIT. While a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute from 2012-2013, Cuthbert had created an open-source toolkit for analyzing musical scores, and used it to examine more than 2,000 medieval French, Italian, and Spanish works.

He introduced Monson and Rehding to two of his undergraduate students, Adam Caplan-Bricker ’16 and Varun Ramaswamy ’15. “The beautiful thing,” Rehding says, “is that Ingrid and I don’t have experience in coding,” and most computer scientists lack a technical understanding of music, but Caplan-Bricker and Ramaswamy bridge the gap. They can parse the structure of music into the language of programming using the deep mathematical sensibility shared by both fields. “We just had to explain to them what we were after, and then they would come out with something much more spectacular than what we could have imagined. I was blown away.”

For a public showcase of digital humanities projects later this semester, the team is now preparing animations of two test pieces—a Thelonious Monk solo and an excerpt from a Bruckner symphony—to demonstrate the toolkit’s range. The Web application requires some fluency in musical theory to create animations, yet its creators hope that the elegant illustrations will make intuitive sense to anyone with an attentive ear. As the tool brings patterns to the surface that listeners may only have guessed at on their own, it allows them to glimpse the music’s internal movements and “what makes it tick,” Rehding says. Introducing people to music in a sophisticated way, “and teaching them to hear things that they might not have heard before—that’s my highest aspiration.”

Watch Monson and Rehding speak about their project: