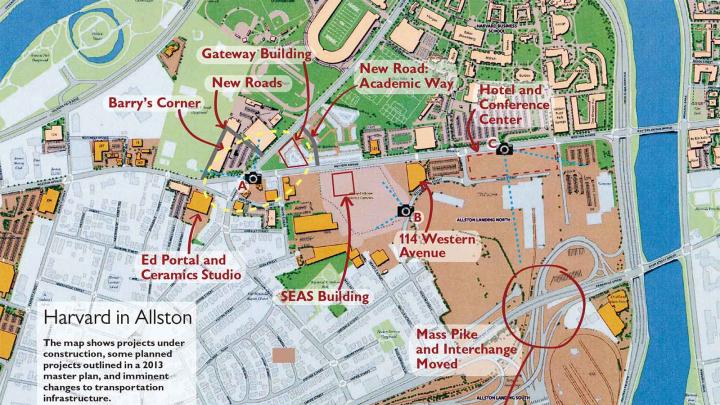

After years of discussions and planning—and more than a quarter-century after the University began buying land for development in Allston—Harvard and its community and development partners are poised to effect significant change there. In coming months, new buildings will open, and new uses and residents will put down roots in the neighborhood beyond the boundaries of Harvard Business School’s (HBS) campus and the athletics complex. In their wake, academic facilities should rise quickly. Furthermore, the long-range goal of redeveloping the vast acreage further east (beneath and beyond elevated roadways, a former rail yard, and other less visible properties), once thought far off in the future, now appears a realistic prospect. (See the map accompanying this article.)

• 2015. Some of the changes are immediately visible at Barry’s Corner, the intersection of Western Avenue and North Harvard Street, where a mixture of academic, retail, residential, and community uses will converge. University development partner Samuels & Associates is completing Continuum: two residential buildings of six to nine stories (both step down toward nearby streets) rising atop a ground-floor base that will host retail uses; the complex will open in August. Across North Harvard Street, the demolition of Charlesview (a low-income housing project that Harvard acquired in a deal that relocated residents to new housing on Western Avenue) will be completed by May.

• 2016. Two projects outlined in the University’s late-2013 Institutional Master Plan (IMP; a regulatory document describing 10-year plans for growth in Allston) will follow closely behind. As early as next year, pending necessary approvals and barring unexpected complications, Harvard could begin construction of a new 500,000- to 600,000-square-foot complex that will house two-thirds of the faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), relocated from Cambridge. This structure could rise rapidly on the already completed foundation of what was to have been a four-building science complex on Western Avenue—before construction was halted in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Meanwhile, a 300,000-square-foot “gateway” building, made possible by the clearing of the Charlesview site, will occupy an important location fronting on Barry’s Corner. The building will anchor the new academic precinct taking shape in Allston within the mixed-use environment envisioned for that intersection. Originally described as administrative offices, it now seems destined for academic uses that might synergize with HBS and SEAS.

• On the horizon. The groundwork for future growth is being laid as land is cleared for an “enterprise research campus” along Western Avenue. An initial, small element of the plan in the IMP is to build a hotel and conference center that will represent first steps in the development of what is to be a 36-acre commercial “innovation district”—one of the largest in the booming Greater Boston area.

As solutions to formidable challenges on the site fall into place, it is becoming possible to “think big” sooner. Ever since the late 1990s, when University planners realized Allston could be much more than a place for overflow from the increasingly space-constrained Cambridge campus (see “South by North Harvard,” September-October 1999), they have also recognized the significant hurdles to be overcome in order to build on the properties acquired there in the preceding decade. (For a condensed history, see “Building—and Buying—a Campus,” September-October 2011.) Charlesview, on a key site in the middle of Harvard’s holdings, was one such obstacle. One of Harvard’s later acquisitions, an approximately 90-acre contaminated parcel owned by CSX, had remained encumbered with the company’s rights of way as it relocated its rail/truck container-transfer facilities to Worcester. This site is also bisected by a Massachusetts Turnpike interchange, which contributes to traffic congestion where the exit ramp meets local roads at the Charles River. Now, the state plans to rebuild the intersection, enhancing local transportation—and opportunities for development of the site and land beyond.

In a late-January conversation with this magazine, executive vice president Katherine (Katie) N. Lapp and University provost Alan M. Garber outlined the progress being made in Allston.

Lapp’s first order of business when she arrived in 2009, she recalled, was to fill the empty retail buildings Harvard had acquired. “We achieved that: 97 percent of all our rentable space is filled with active and vibrant uses,” including swissbäkers, Stone Hearth Pizza, and CrossFit Boston, she reported. “We also opened a new ceramics studio, at 224 Western Avenue,” that is actively used by faculty members, students, and the neighborhood community. The Ed Portal, a project that offers performances, workshops, and classes for adults, as well as scholarships, a summer-jobs program, and mentoring by Harvard student volunteers for local children, will reopen in larger quarters in the same building at a rededication February 21, she said. (President Drew Faust and Boston mayor Martin J. Walsh will officiate.) At Barry’s Corner, the University has added lights and benches to a grove of trees in front of the Charlesview site. And 114 Western Avenue, a conference building that will eventually be used by administrators at SEAS (whose new building will rise next door), is home to the new Launch Lab, occupied by alumni of the i-lab (University space for entrepreneurship—for more information, see harvardmag.com/hi-lab), who have moved on to the incubation phase, and are renting the space.

Alongside the eye-catching high-rise construction, the local infrastructure is being improved. The Continuum residential and retail project is bounded by two new roads: Smith Field Drive and Grove Street. Once Charlesview is demolished, Harvard will build Academic Way, running between Western Avenue and North Harvard Street, said Lapp, to alleviate traffic at Barry’s Corner and provide access to the planned gateway building. (It will also facilitate construction of the SEAS and gateway structures.) “Public-realm improvements”—new sidewalks, lighting, and landscaping—will be installed along Western Avenue.

These steps set the stage for the main near-term events under the IMP. Construction of the science building could begin in 2016, Lapp said, and be completed by 2019 under the current schedule.

Garber noted that the planning process for that building has led to extensive, productive discussions about the future of SEAS that have “implications for the entire University.” SEAS faculty members, working with architect Stefan Behnisch, have been thinking not only about lab and office configurations and “the kinds of services that they want to have,” said Garber, “but also about how teaching spaces might accommodate their aspirations for pedagogy,” whether in the classroom, the lab, or elsewhere. (For faculty perspectives on these design issues, see harvardmag.com/allston-15.) “We want to make sure the new building accommodates the needs” of current and future students, he continued.

Although the building will not house the entire SEAS faculty, Garber observed that the school will nevertheless be more integrated than it is now, with its faculty “spread out over approximately 17 different buildings. The groups going to Allston will have great space for collaboration.” (Computer science, biological engineering, and mechanical engineering will relocate; applied mathematics, applied physics, electrical engineering, and environmental science will remain in Cambridge.) He also confirmed that the foundation on which the building will rise could accommodate more construction. “Our discussions and our thinking are focused on this first building,” he said, “but we are constantly aware that we have great potential for additional construction.”

As for the gateway building, Garber confirmed that during the past year, “We reached a decision that [it] should be available for academic uses.” Which uses are still “a topic of intensive, ongoing conversations.” The committee “tasked with thinking about how best to take advantage of the opportunities” in Allston, he added, aims to engage “the entire University community” in answering that question. A component of a professional school is “not off the table”—and certainly several of them are severely space-constrained today. The units chosen will likely have intellectual and academic connections to many parts of Harvard, ideally including HBS and perhaps SEAS. Construction might follow a timetable nearly parallel to that of the SEAS building if the necessary approvals can be secured.

Lapp also addressed two other components of the 2013 master plan: a basketball arena that could accommodate larger audiences (nestled within a larger complex, including affiliate/graduate-student housing, and/or office space, with ground-floor retail uses, according to the IMP), and renovations to Harvard Stadium that would add heated luxury boxes, while reducing the total seating capacity. “The stadium is continuing to be looked at,” she said, “as is the basketball [arena], but this is a 10-year plan.”

Turning to the enterprise research campus, envisioned for a 36-acre parcel across Western Avenue from HBS and east of the SEAS site, Garber said that the “time is propitious” for such a commercial development. “Boston has an extraordinary concentration of intellectual capital and of research activity, particularly in the life sciences and technology,” he pointed out. The city is also “an extremely attractive location for knowledge-intensive industries, and virtually every major pharmaceutical company has or seeks to have a research presence in the Boston area.” Kendall Square, the epicenter for such tenants, near the MIT campus, totals 30 acres, he said. Elsewhere in Boston, “There are pockets of land where research-intensive businesses can be developed, but nothing quite like this [parcel] that I am aware of.”

Because Harvard, Boston University, MIT, and Tufts are all near the site, he continued, “If you wanted to develop your plan for dealing with malnutrition in Africa, you have access to scientists and to students who will be passionate about solving worldwide problems. You’ll have also access to a philanthropic community…committed to many of these causes. We believe that the enterprise research campus will be a very attractive location for large research-intensive companies, for commercial startups, and for social enterprises who want to tap into the wealth and talent that are available in our area.”

Such activity will, in turn, “contribute to the academic environment, in part by enabling those members of our community who wish to interact with companies to do so,” Garber said. What construction will appear on the enterprise campus (beyond the hotel and conference center detailed in the IMP) has not yet been decided, but Lapp indicated that the “goal is to create a 24/7-type community,” implying a broad mix of uses.

That prospect is on the verge of critical enhancement as transportation improvements come into view. Gesturing to a map that shows how the Massachusetts Turnpike sprawls across and above the 90-acre Allston Landing property formerly used by CSX, Lapp explained that the state plans to straighten the road, beginning in 2017. Harvard will donate the land to move the highway and build a new interchange, she said, speeding the project and trimming its cost—and once the new roadway is operational, the state will “knock all this spaghetti of entrance and exit ramps down.” Harvard will donate the land to move the highway and build a new interchange; once the new roadway is operational, the state will “knock all this spaghetti of entrance and exit ramps down.”

The new local road network, at grade level, effectively makes available an entirely new parcel of property: 40 to 50 additional developable acres, Lapp explained. The Boston Society of Architects, recognizing the opportunity, arranged pro bono charettes by two teams of local architects, who worked to devise ideal but practical schemes for pedestrian and bike access, parkland, and public transportation. These were presented at a neighborhood meeting in Allston last September, and were greeted with enthusiasm.

Harvard has also given the state sufficient land for tracks to facilitate more trips on the commuter rail line that serves communities directly west of Boston. “In exchange,” Lapp said, officials “have agreed to put in a commuter rail station” (with the University reportedly paying one-third of the cost). That raises the possibility of rail connections between Allston and other parts of Boston—a huge potential benefit in a neighborhood not served by the subway system, and a further opportunity to diversify the enterprise zone. “We are constantly aware that we are thinking about the University of the future. We need to think decades into the future, not years.”

Construction of the enterprise campus might begin in three to five years, but Garber acknowledged, “There are many potential sources of delays in a planning process of this scope and magnitude. They are not all predictable. Some can come from getting appropriate approvals from government agencies, some can come from surprises that you find out about the land or engineering challenges—the list goes on and on. Allston represents a tremendous opportunity for the academic future of the University. But…as we plan for new academic sites in Allston, new buildings, new forms of academic space, there are many interdependencies that we need to take into account. If you free up space in Cambridge, what is the best use? And in fact, you don’t start by thinking about filling space in Allston, you start by thinking about what are our needs in the University, what challenge to our growth can we overcome by taking advantage of the opportunity to build space in Allston. So that is an inherently complex question to answer. And it is critically important for us to get it right, because we are constantly aware that we are thinking about the University of the future. We need to think decades into the future, not years.”

Those are indeed appropriate caveats. Even so, Harvard’s future in Allston, and Allston’s future with Harvard, seem considerably clearer than they were a few years ago.