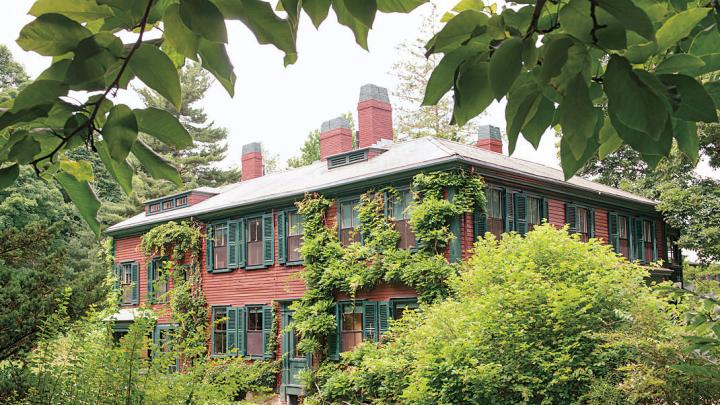

Walk through the front archway at the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, and note how the dirt carriageway gently hugs an island grown wild with ferns, winged euonymous, and native barberry. In the middle, ivy runs up the rough and reddish trunk of a 90-foot Eastern hemlock. “Olmsted planted that soon after he bought the property in 1883,” park ranger Mark D. Swartz explained during a tour of the Brookline, Massachusetts, site. “He envisioned that it would eventually be a towering centerpiece that would command attention as people walked in.”

Some 131 years later, it does. Patient and persistent, Olmsted, A.M. 1864, LL.D. ’93, angled the archway toward the tree, not his house, and likely knew that in time the structure would be hidden by boughs and foliage. America’s most famous landscape architect (with two honorary degrees from Harvard) “believed the natural world was a powerful medicine,” Swartz added, “an antidote to the adverse effects of the manmade urban environment that was rapidly expanding during his lifetime.” Here, the eye, first caught by the tree, follows the curving drive as it disappears behind the hemlock. Though small, the landscape Olmsted sculpted around his home holds pathways lined with mountain laurel and local pudding stone, a solitary American elm set on the rolling lawn, rock stairs patchy with moss that lead to a shady hollow rich with vines, rhododendrons, cotoneasters, yews, and a shagbark hickory tree. All encouraged the same sense of playful exploration, of grand mystery in the “natural” world, that imbue New York’s Central and Prospect Parks, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and his other public projects.

At 61, Olmsted was famous when he and his wife, Mary Cleveland Perkins Olmsted, bought the farmhouse, naming it “Fairsted.” He was so intent on having the place, which sat on nearly two lush and hilly acres, that he cut a purchase deal with the elderly sisters who owned it: they moved into a cottage his son designed at the edge of the property, to live rent-free for the rest of their lives.

Still recovering from his final political battles over Central Park, Olmsted was lured to Boston as much by what would become the Emerald Necklace as by his friends and collaborators, the architect H.H. Richardson, A.B. 1859, and botanist Charles Sprague Sargent, the first director of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. They both lived nearby, and Isabella Stewart Gardner soon moved in next door. She was already collecting the art that would later fill her Boston museum, adjacent to Olmsted’s earliest Boston project, the Back Bay Fens. There, he helped solve an engineering and public-health problem caused by chronic flooding and excess sewage. “He recreated a salt marsh that had been there, but enhanced it with a variety of new plants,” Swartz explained, building a more scenic testament to the original landscape. Pathways were added around the marsh, as was a carriageway, which became known as the Fenway, and two bridges, one designed by Richardson.

Gardner’s manse and other early estates still stand along the winding road to Fairsted. The Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site opened to the public in 1981, having been purchased the previous year directly from Olmsted’s firm, which was still there. The site now includes seven acres (five were bought from the Gardner estate and are conserved to protect the viewshed) and the original residence. Also open is the two-story addition that was built in stages, mostly after Olmsted retired in 1895, to house the landscape-architecture firm he founded and others continued to foster.

A new permanent exhibit, Designing for the Future: The Olmsteds and the American Landscape, fills most of the first floor of the house and reflects the monumental impact of Olmsted’s philosophy and work, emphasizing the collaborative nature of his legacy. “It was not just Olmsted’s vision,” Swartz says, “that made a major contribution to American landscape architecture.”

Others took his ideas, as well as their own, into the future—in particular, Olmsted’s sons, John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., A.B. 1894. They worked with their father, then took over the firm when dementia forced his retirement. (He spent the last five years of his life at McLean Hospital, whose Belmont, Massachusetts, site he had helped choose years before; see Vita, “Frederick Law Olmsted,” July-August 2007, page 38.) Also pivotal was Charles Eliot, A.B. 1882, the son of Harvard president Charles William Eliot, whose cousin Charles Eliot Norton, Harvard professor of art history, was a good friend of Olmsted’s. The younger Eliot apprenticed with Olmsted in 1883, then returned as a leading partner of the renamed Olmsted, Olmsted and Eliot, in 1893. The nation’s first landscape architecture program was established in Eliot’s honor at Harvard.

The family presence is only lightly felt at Fairsted. Olmsted married Mary, his brother’s widow, in 1859, and adopted her three children, including John, who was already 31 and a landscape architect when the family moved to Brookline. (The couple’s own son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., was about 13.) Vintage photographs of the former interiors are hung on walls, and visitors can flip through photo albums in the Olmsted-designed, pebbledash stucco-walled plant room. But the addition, where the firm was headquartered, has been restored and recreated circa 1930, when F.L. Olmsted Jr. was chiefly in charge and business at its peak, requiring about 70 employees. The sparsely decorated rooms—where bare bulbs on cords and on swinging metal arms light wooden tables and simple tools—capture the painstaking artistry of nineteenth-century design work: pen nubs and inkwells; a can of Pounce (powder used to blot ink); colored pencils and the sandpaper used to sharpen them; a velvet case for compasses and a metal canteen, both taken on field visits.

Pinholes on the tables mark where thousands of landscape plans were labored over, and where lead drafting “whales” weighted the wooden arcs formed to draw Olmsted’s meandering paths. Employees serving as “copiers” sat at a “light table,” tracing fine lines of a design on paper uplit, through glass, by metal lamps on the floor. The tracings became blueprints: drawings were placed atop paper treated with cyanide salts and rolled through windows onto racks outside to develop in the sun. Later, the 1904 Wagenhorst Electric Blue Printer, also on display, brought that process indoors.

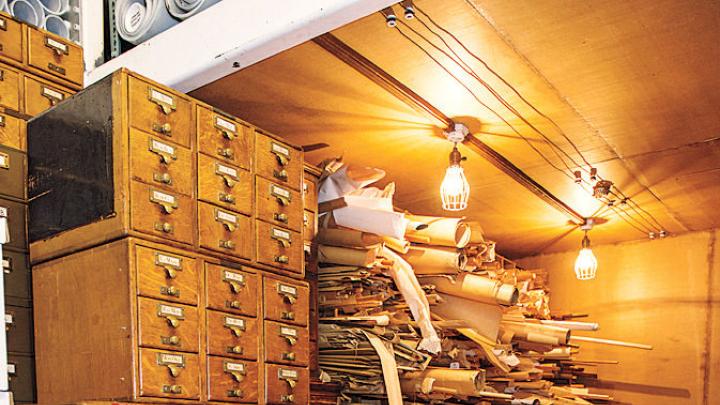

By the time the federal government took over the site, business had dwindled for years and the firm had consolidated operations on the first floor. Some 139,000 paper plans were found in a storage vault, Swartz reports, most of them “dirty, stained, brittle, and torn,” he adds, “a few with mold growing on them.” It took paper conservators nearly 15 years to inventory and repair them. Altogether, more than a million archival documents are stored on site; researchers may work there by appointment.

The restoration work outside was and is just as carefully considered. The hollow to the right of the hemlock and carriageway in front of the house, for example, is maintained as “wild,” Swartz says. Olmsted eschewed flower gardens, preferring the picturesque landscape and a palette of greens. Here, visitors descend rock steps into the hollow to find his differentiated shades, textures, shapes, and sizes cool to the eye, and more soothing to walk through.

Fairsted is ultimately a manmade environment. “He cut down all the elms out here,” Swartz explains, “except the one he wanted, in the middle of the South Lawn.” That tree survived until 2011. Much discussion of historic and scholarly interpretations and practical realities (efforts to propagate cuttings from the original elm failed) led to replacing it in 2013 with a new, disease-resistant variety, the Jefferson elm. The young specimen stands alone on the lawn, cordoned off by ropes. “We’re protecting it,” says Swartz. The hope is that half a century from now, Olmsted’s visionary design will again offer the sense that nothing was placed here, that everything simply evolved.