“In sculpture, you are always fighting the deadness of a thing,” says Murray Dewart ’70, paraphrasing Victorian critic Walter Pater. “The secret of sculpture is getting the feeling that the life force is pushing from the inside out. You get it in bread.” He picks up a fresh baguette. “This has risen two or three times,” he explains. “The form is being inflated from the inside out. That is what great sculpture does. [Alexander] Calder or George Rickey wanted to get things moving in the sunlight—the spark is the reflection of light as the thing turns. It has to come alive.”

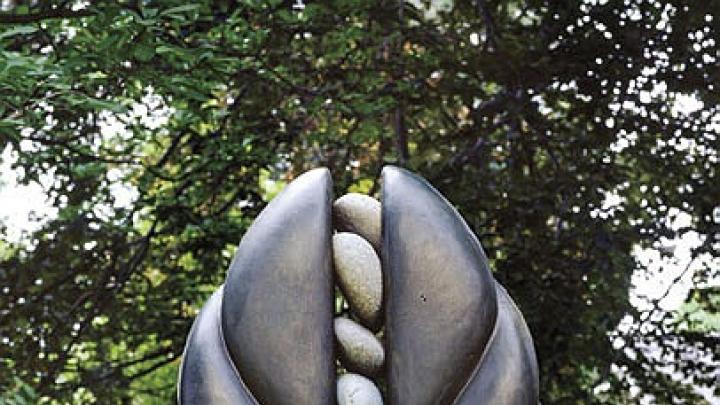

One of Dewart’s sculptures, Sabbath Loaf (2005)—installed this summer at The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, Massachusetts—in fact resembles a bronze loaf of challah, halved and standing vertically, like a sandwich with a filling of smooth river stones. Much of his work is in bronze and granite: the forms are simple, often resembling gates, and they feel rooted, like the five-foot-tall Sun Gate installed in the McKinlock courtyard of Harvard’s Leverett House. Across the planet, in the International Sculpture Park of Fuzhou, China, the 12-foot Earth House Hold (2003) uses two massive granite pillars to support a bronze grid with a bronze arch surmounting. “When the granite is rough-cut in the right way,” Dewart says, “you can still feel the mountain speak.”

Dewart (rhymes with Stuart; www.dewartsculpture.com) makes sculptures that often occupy gardens, where their simplicity both contrasts and harmonizes with the live landscape. Many viewers find an Asian sensibility in his works. “There’s a spiritual component in me, as there is in old stone and forms coming out of China and Japan,” he explains. “Their central element has a balanced, harmonic kind of equilibrium, an emblem of what I am yearning for, not necessarily of what I’ve found.” Some Chinese buyers apparently do appreciate his efforts; Beijing also has two of his works in its international sculpture park.

After college (where he concentrated in English but did some seminal sculpting in Carpenter Center), Dewart returned to his home state of Vermont, where he and his wife, Mary, lived on a remote, 100-acre farm at the end of a road near Lake Champlain. Over seven years, he taught himself sculpture, beginning with wood carving, which he practiced for two decades. He recalls having “a great adventurous, independent youth,” doing things like working as a roustabout in a Wyoming oil field. “If you didn’t take risks early,” he says, “you’d never be crazy enough to do something as dangerous and financially risky as becoming an artist.”

He notes also that “you have to be clever to survive as an artist.” His works began selling only about 20 years ago, so Dewart has held many day jobs. He has taught sculpture often, including 10 years at Saint Anselm College in New Hampshire. He recalls attending a black-tie dinner at the Fogg Museum where, poignantly, he locked eyes with a neighbor and fellow artist who was serving him. Yet, “if you ask your art to support you early in your career, you’ll probably be doing fairly stupid things as an artist,” he says. “When you burden your art with ulterior motives, you can ruin it.”

In 1978, just before their second son was born, the Dewarts abandoned their rural isolation for Boston, where he vowed “never to be cut off again.” He started organizing sculptors’ dinners to offset “the loneliness of being an artist. Art grows from nature, and it also grows from other artists, both long-dead and living ones.” The dinners grew into the Boston Sculptors Gallery, now 20 years old, with 36 members, half male, half female. They’ve staged shows all over the world, from Peru to Paris, including a major assemblage of works installed at the Christian Science Plaza in Boston this year. “It’s the community I wanted,” Dewart says.

But the sculptor’s process requires solitude, too. Each day begins with a blank sheet of paper at dawn; Dewart writes or draws whatever comes to him. He’s now on his sixty-fifth volume of this daily journal. “I am trying to please something in the eye and the heart,” he says. “You have to come into the studio and have something powerful happen to you.” When he enters his studio, “there’s a certain amount of chaos,” he says, and you never know when something will trigger an idea. It might, for example, be a fragrant baguette.