James Henry Blake entered Harvard’s Lawrence Scientific School in 1864, an exciting time to be a naturalist. Louis Agassiz, director of Harvard’s five-year-old Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), had embarked on a series of collecting expeditions, supported by wealthy patrons, and as one of Agassiz’s students and assistants, the young Blake, then in his twenties, began to draw and record the characteristic soft features of mollusks collected during the 1865-1866 Thayer expedition to Brazil. In 1871, when Agassiz began a second voyage to South America aboard the new U.S. Coast Survey steamship Hassler, Blake went with him.

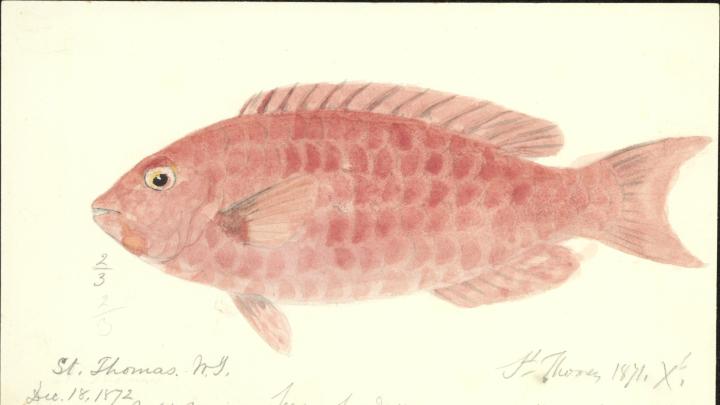

Approximately two dozen of Blake’s drawings and watercolors, many from the Hassler expedition, are now on view at the MCZ’s Ernst Mayr Library as part of a new special exhibit on the zoological artist. According to documents prepared by the MCZ’s special collections librarian, Robert Young, who organized the exhibit, the ship left Boston in December 1871, sailed through the Caribbean, and circumnavigated South America before finally reaching San Francisco nearly nine months later with a reported 30,000 specimens on board. (Alas, a handful were allegedly destroyed when, in a drunken spree, the Hassler’s sailors siphoned off the whisky used as a preservative.) The minute detail and brilliant colors of the works on display—all carefully labeled with date and location of collection—showcase the diversity of the specimens collected, from delicate snails and tropical fish to eels and seahorses. “If I am allowed to make these collections available by the proper means of preservation,” wrote Agassiz in 1873, “we have now the greatest working Museum in the world; the one, that is, which supplies the most extensive and varied material for special and comprehensive zoological research.”

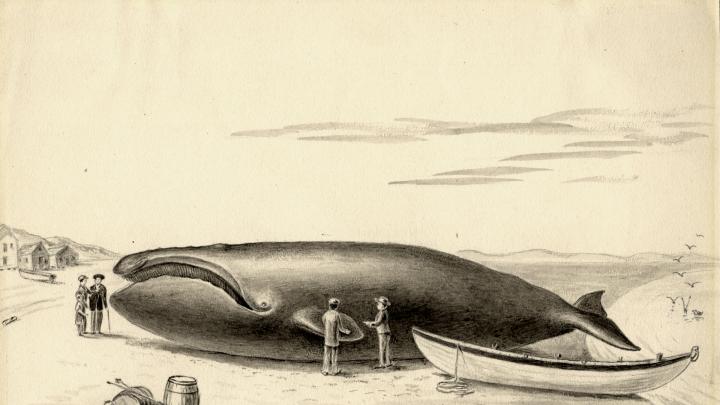

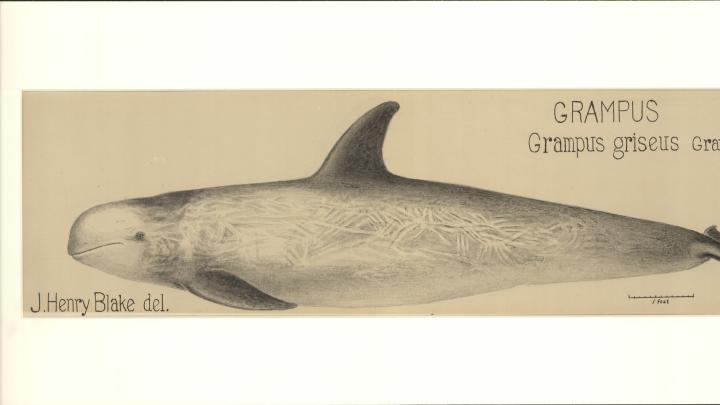

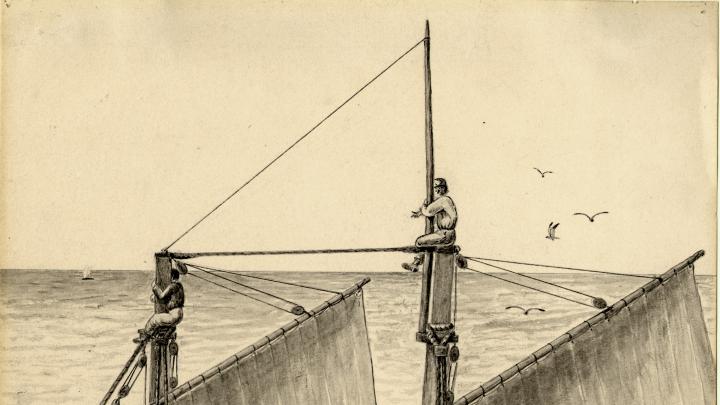

Although Blake is primarily remembered as a malacologist, he was also fascinated by whales. A series of large, detailed drawings of various species currently on display was presumably commissioned by MCZ mammals curator Glover M. Allen for his 1916 book, The Whalebone Whales of New England. An additional series of six drawings on temporary display last week chronicled the dramatic 1864 sighting and capture of a rare (and now highly endangered) right whale; its skeleton, later offered to the nascent MCZ, is still on view in what is now the Museum of Natural History (HMNH). It took twenty-five years for the skeleton to be mounted following the whale’s capture; on the occasion, Louis Agassiz’s son, Alexander, then director of the MCZ, recalled in the museum’s annual report how he had been sent by his father to Provincetown to prepare the enormous, rotting carcass—an “unpleasant task.” (Blake, preparing an account in 1912, noted that the 48-foot-long whale produced more than 83 barrels of oil and a thousand pounds of baleen.)

Following the Hassler’s return, Blake continued his detailed drawing and study of the MCZ’s new collections of fish and mollusks until 1875 (when funding ran out two years after Louis Agassiz’s death). But he maintained a lifelong passion for sea creatures: he later worked as an artist for the Vineyard Sound Survey of the U.S. Fish Commission, the U.S. Geological Survey, and Mississippi Geological Society, and helped found the Boston Malacological Club. His great-great-granddaughter, Kristen Blake, has worked with Harvard museums and collections for nearly 20 years, and is now the visitor services supervisor at the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture (of which the HMNH is a part). Her first Harvard job was at the MCZ, as a curatorial assistant in the ichthyology department; occasionally, while cataloguing the collections and performing basic upkeep, she would encounter Hassler specimens that James Henry Blake had helped collect.

Throughout his life, Blake kept an extensive scrapbook filled with photographs, clippings, and manuscript leaves, including a detailed account of the Hassler expedition. Blake was “very protective” of the voyage’s history, Young notes in the exhibit’s supporting text, and would often send letters to correct later published accounts. His fondness extended to the MCZ, and he later bequeathed most of his artwork and personal collections, including his scrapbook, to the museum. And Blake never forgot his mentor Agassiz; in classes, as Blake would tell lecture audiences later in his life, he always took the desk closest to the professor.

For more on Louis Agassiz, see current MCZ director James Hanken’s review of a recent biography of Agassiz: “A Scientist in Full: The fruitful, flawed Louis Agassiz.” See also a 2009 account of the MCZ’s 150th anniversary, “The MCZ at 150.”

![Image courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, MCZ, Harvard University. Not to be reproduced without permission. “The Whale ‘sounding’ or diving after having come to the surface to breathe of [sic] ‘blow.’ In making the longer dives the flukes of the tail are thrown thus high out of water. The boats are now in pursuit.”](/sites/default/files/styles/topic_teaser_mobile_d7/public/img/article/0713/blake_2sm.jpg?itok=9WO9F-_J)