Barefoot and in a bright red dress, she has the body of a young woman, but her face is older and worn. She looks left, out of the frame, holding the handle of a wooden cart on which is roped a figure primitively wrapped in dirty burlap, a foot barely visible. Her name is Nubia. She is 14. The figure is her husband’s body. The photograph has the grace and mystery of a piece of art, but goes beyond art to the heart of the anguish of war and the price of revolution on a very personal level.

In the years since she first took up the camera at Harvard, Susan Meiselas, Ed.M. ’71, has created a body of work that combines the graphic intelligence and artistry of photography with the inquisitiveness of a social scientist. Though her photographs often have political resonance, her passion is less to reform the world than to understand it. Now a major retrospective, Susan Meiselas: In History, mounted by the International Center for Photography in New York, brings together 40 years of her work. The exhibit, on display this spring at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, is now touring Europe.

The retrospective’s three sections—a gritty look at carnival strippers in New England country fairs; powerful journalistic images of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua; the creation of a history of Kurds using 100 years of visual relics—display chronologically how Meiselas has always been driven to collaborate with her subjects in as many ways as possible.

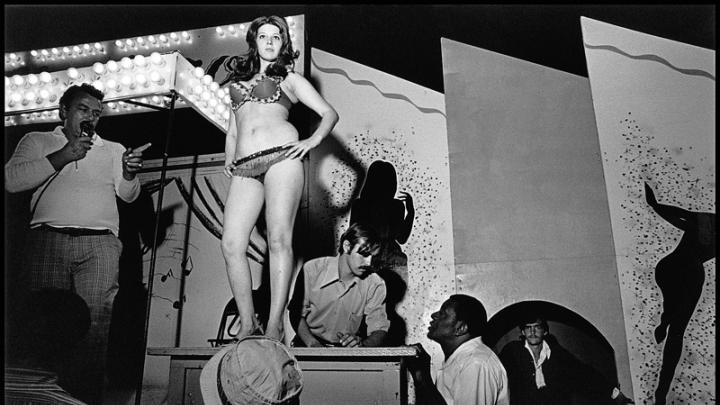

Her 1976 book, Carnival Strippers, drawn from three summers of work in Vermont and Maine, includes extensive transcriptions from tape recordings she made at the time. The rawness of the book’s pictures recalls Robert Frank’s work in The Americans (1959). But her interviews expand the context of her uncompromising photographs, presenting a surprisingly complex, compassionate look at these women who, by and large, are simple farm girls trying to make a living as best they can in a seedy world. By emphasizing the voices of the women, Meiselas goes well beyond both the confines of art photography and the strictures of academic social science.

The chasm between the tantalizing vision of sexuality that the strip shows offer and the very human world that Meiselas records fits into a documentary tradition that seeks to produce meaningful art. Meiselas began working at a time when John Szarkowski, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, was the philosophical giant of the photographic art world. His seminal 1967 MOMA show of works by Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Diane Arbus heralded a reign of “street photographers” whose philosophical underpinnings were best codified in Susan Sontag’s 1966 book Against Interpretation. “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art,” she wrote, arguing that to seek understanding from art is to impoverish its meaning. Sontag saw photographs as objects unto themselves, to be viewed for their spatial and tonal relation to the frame, without any attempt to provide a larger, more “meaningful” context. (At one of Winogrand’s lectures at MIT in the early 1970s, upon seeing the photograph of a bloodied older woman lying on a New York street, a sarcastic questioner asked, “What did you do after you took that picture?” Winogrand replied, “I think I took a vertical.”)

Meiselas took a very different approach to documentary photography. Her carnival-stripper images combine the visual energy of a Winogrand street scene and a Diane Arbus-like attraction to a strange, almost perversely exotic world with the tools of a social scientist—in this case, camera and tape recorder. This approach grew from her passion for anthropology, which began with work on a Navajo reservation in high school, and later in classes at Sarah Lawrence College, where she earned her B.A. in 1970. Her choice of the camera as her principal tool for exploring and understanding the world around her was somewhat serendipitous. It began with classes she took with lecturer on photography Len Gittleman and Barbara Norfleet, associate of the department of visual and environmental studies, when Meiselas was pursuing a master’s in visual education at Harvard. “It could just as easily have been a compact video recorder,” Meiselas says, “if such a thing had existed at the time.”

The strippers are gone from New England carnivals. They have become a part of history. Meiselas’s next significant project would take her to Nicaragua, at her own expense, to explore a burgeoning revolution. Today, most who know her pictures think of Meiselas as a war photographer, based on her decade of work in Central America. But for her, it began as another quest to find meaning with her camera; that she recorded history was accidental.

The Nicaraguan photographs caused a sensation. Her first foray into journalism flooded the world media, and individual pictures like “Molotov man” became iconic, finding their way not just into the international press but onto Nicaraguan matchbooks, stamps, murals, and Sandinista propaganda pamphlets.

One wall of the In History show arranges the Nicaraguan material in three parallel tracks. Color prints of the individual photographs stretch along the middle row. Above them, the top tier displays magazine and newspaper clippings, showing where these images appeared in the media. The bottom row displays contact sheets and work prints of the same scene, revealing other options her editors had considered. The interplay of these three levels amounts to an investigation of the visual communication process. This is photography not as art, but as news—or news raised to the level of art, and art transformed into elements of history.

In the chaos of a war there was time only to photograph. Understanding would come a decade later, when Meiselas and longtime companion (and eventual husband) Richard Rogers ’67, Ed.M. ’70 (see “The Windmill Movie,” May-June 2009, page 17), returned to Nicaragua to make the 1991 film Pictures from a Revolution with her filmmaking partner, Alfred Guzzetti (now Hooker professor of visual arts). Small video screens embedded in the exhibition wall show five segments from the film, each focusing on an individual photograph as Meiselas tries to track down the people in her original images, seeking to understand both the story behind the image and the revolution’s effect on individuals. It was only during filming that Meiselas learned that the young girl with her husband’s body whom she’d photographed a decade earlier was just 14 at the time. In the video, Nubia wears tiny gold earrings—the same earrings as in the photograph. “I buried him all by myself,” she says. “The National Guard shot at me from helicopters and I saved myself by crawling under the cart. They saw my red dress.” Some of Meiselas’s subjects felt the revolution had been betrayed, and things were little better under the Sandinistas than under Somoza, especially with the rise of the Contras—who, said one man, Justo, had cut off the alas, the wings, of the revolution.

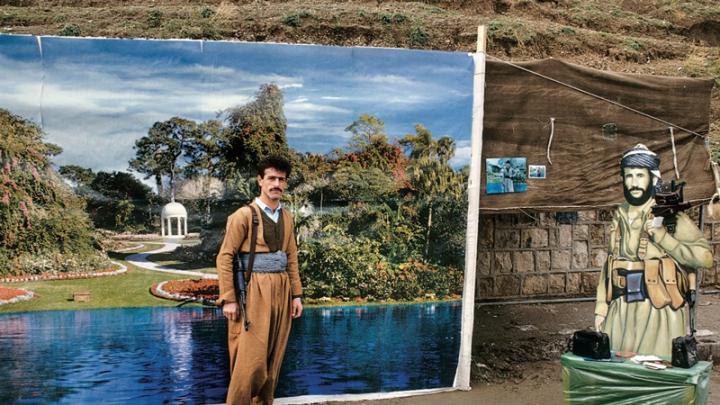

In 1991 Meiselas went to Kurdistan with anthropologist Clyde Snow of Human Rights Watch to document the unearthing of the remains of genocide committed in the Kurdish towns of Arbil and Koreme under Saddam Hussein. Trying to understand the devastation and human tragedy she found, she recognized that she “couldn’t photograph the present without understanding the past.” In other words, she needed to construct a history, and realized that she could build one from the works of photographers and reporters who had preceded her. “What I suddenly see,” she says, “is that there’s a whole timeline of people like me.”

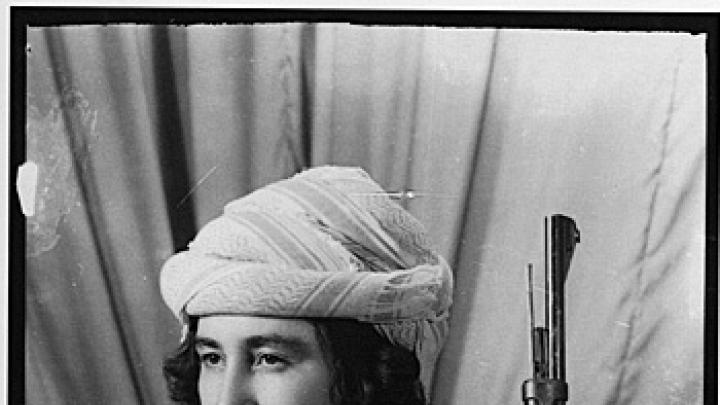

Meiselas took on the monumental task of reconstructing 100 years of Kurdish history by collecting and reproducing the artifacts of hundreds of photographers, newsmen, and chroniclers. A MacArthur grant freed her from the constraints of journalism to pursue this venture into cultural anthropology. The result was her book Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (1997), which she refers to as “a timeline of image makers.” In the exhibit, this section is presented by glass cases filled with photographs and other original materials; a video Meiselas shot in 1992 of local photographers taking formal portraits on the streets of Arbil; and a four-screen projection of material from the book itself, with her own narration.

In the 40 years since she first looked to the camera as a collaborator in her quest to explore, understand, and ultimately reconstruct her world, Meiselas has generated not only unforgettable photographs, but collections that challenge conventional beliefs (the carnival strippers), document history in the making (Central America), and create a unique understanding of history itself (the Kurds). Her images are at once artful and guileless, combining with disciplined skill the power of representation and an honest affection for her subjects.