| Rituals | Dining | Reunion | Goings On |

|

People are on the move on Commencement morning. Before eight o'clock the guests are streaming through the Massachusetts Avenue gates into the Yard, headed for Tercentenary Theatre, the grassy area between Memorial Church and Widener Library. Graduate-degree candidates congregate in Sever Quadrangle; faculty members, administrators, and assorted government officials assemble near Massachusetts Hall. Honorary-degree recipients arrive from the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. Reunioners join their classmates in the Old Yard, and seniors gather and assorted government officials assemble near Massachusetts Hall. Honorary-degree recipients arrive from the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. Reunioners join their classmates in the Old Yard, and seniors gather in their Houses before setting off for a special service in Memorial Church.

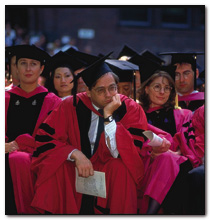

Eventually, almost everyone ends up on rigid plastic or folding wooden chairs, awaiting the "joyous peal" of the deep-toned bell of Memorial Church that signals the 10 o'clock start of the morning exercises. In 1997, more than 5,000 degrees will be conferred on members of the various graduating classes, assembled under the reds, blues, golds, and whites of the Harvard and Radcliffe flags that have graced the festivities since the University's 350th birthday celebration in 1986. The degree candidates are joined by three or four times that many guests. Despite the changes in scale and decoration, much in today's Commencement would be familiar to alumni of generations past, especially the academic robes and student "parts." Here is a brief guide to what the assembled company will witness.

Academic regalia recall medieval times when scholars were clerics who wore robes, hoods, and capes to shield themselves from European winters. Today's academic gown almost certainly evolved from the inner robes or tunics of those medieval scholars. The velvet facings on doctoral robes mimic the way ancient linings draped when the robes fell open, and the present academic hood stems from the medieval cowl, as does the "tippet" worn by the masters of the Harvard Houses.

Academic fashion at Harvard traditionally has been restrained. An entry from The Laws of Harvard College of 1807 prescribed that "Every Candidate for a first Degree shall be clothed in a black gown, or in a coat of blue grey, a dark blue, or a black color; and no one shall wear any silk nightgown, on said day, nor any gold or silver lace, cord, or edging upon his hat, waistcoat, or any other part of his clothing, in the College, or town of Cambridge."

In 1897 a system to govern the wearing of academic regalia in this country was established by the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume. The scheme was designed to "subdue the differences in dress arising from different tastes, fashions, and degrees of wealth." Harvard adopted it by a vote of the Corporation.

|

The system is simple. Bachelors' and masters' caps--chiefly mortarboards--have long black tassels; doctors' tassels may be gold. Harvard presidents may wear gold tassels, though no rule requires it. (Nor does a rule govern whether the tassel drapes to right or left. As an expert once noted, "A gust of wind could change your academic standing in a moment.")

Gowns are designed for bachelors, masters, and doctors, respectively. The first has long pointed sleeves; the second has long sleeves ending in curved pouches well below the knee; and the doctor's gown, crimson at Harvard since 1955, is faced with velvet, with three velvet bars on full round open sleeves. Every Harvard academic gown has an embroidered crow's foot near the yoke on each of the facings, double for earned degrees and triple for honorary. The color of the crow's feet designates the faculty conferring the degree. Many of the colors have historic connotations: white for Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges comes from the Oxford and Cambridge bachelors' hoods; dark blue for the doctor of philosophy is the color of truth and wisdom; medium gray has long represented Business; lilac, Dental Medicine; and yellow, the School of Design. The scarlet for Divinity follows the traditional color of the church and the crucifixion; light blue for Education is again the color of truth and wisdom, as is peacock blue for Government. Purple for Law recalls bygone kings who made laws; and Medicine's green is the color of medicinal herbs.

It is the hood that has the greatest degree of color and symbolism. A master's hood is three and one-half feet long, the doctor's is four feet, but both have a silk lining in the colors of the university conferring the degree. All Harvard hoods are black on the outside, and lined in crimson--the color, officially described as that of arterial blood, formally adopted as the official livery color of the University in 1910.

Commencement "parts" recall the days when graduating students had to perform public "acts" to demonstrate their educational attainments. Harvard's Commencement is one of very few where students still play so prominent a role. Three students selected in a University-wide competition deliver the parts: first a senior declaims a Latin salutatory, or address of greeting; then a second senior and a graduate student deliver an English address each, or, more specifically, an "oration," "dissertation," or "disquisition," depending on whether the speaker's degree has been granted summa, magna, or cum laude.

Students choose their own topics. President Josiah Quincy's daughter, describing the 1829 Commencement in her journal, noted that senior Oliver Wendell Holmes gave a "funny speech." Theodore Roosevelt, A.B. 1880, spoke on the "Practicality of Equalizing Men and Women before the Law." W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, discussed "Jefferson Davis as a Representative of Civilization," pointing out that "As the crowning absurdity, he was the peculiar champion of a people fighting to be free in order that another people should not be free."

The only person--at least in recent Harvard history--to deliver two parts is Massachusetts governor William Weld '66, J.D. '70. He gave the Latin salutatory in 1966 and the graduate English address in 1970, the same year Kirsten Mishkin became the first woman to give a part: she delivered the Latin salutatory.

Now for the ceremony. At 8:55 the Commencement caller sends the academic and alumni processions off, down paths flanked by applauding seniors, from the Old Yard into Tercentenary Theatre. Palpably if invisibly in the procession walks the endless train of ghosts that Emerson spoke of more than a century ago at Harvard's bicentennial (see page 32F). As the president's division nears the Theatre, the Harvard Band stikes up a jubilant fanfare. President Neil L. Rudenstine takes his seat--on the triangular Jacobean chair used at every Harvard Commencement since the eighteenth century--in the center of the platform erected on the south side of Memorial Church. When the rest of the procession has been seated, the University marshal signals the Memorial Church bell to herald the start of the morning exercises.

These begin when the sheriff of Middlesex County proclaims, "The meeting will be in order!" The chaplain of the day offers a prayer, the Commencement choir sings an anthem, and the marshal introduces the student speakers.

When they have finished, the conferring of degrees begins. With exuberant support from the audience, the president acknowledges the candidates from the various faculties, who rise and stand in place. They will receive their diplomas later, at ceremonies in the Houses and graduate schools. Last, the graduating seniors are admitted to "the fellowship of educated men and women." President Rudenstine has inaugurated a gracious custom: he next invites the new degree recipients to applaud all the family members, teachers, and friends who have supported them throughout their academic careers.

The president next awards honorary degrees, a Harvard tradition since Benjamin Franklin received an honorary master of arts in 1753. One of the honorands will address the Harvard Alumni Association's annual meeting, held in the same space in the afternoon. The convocation then rises for the Harvard Hymn. Sung in Latin, it makes three requests of the Deity: that the trustees have integrity (Integri sint curatores), the faculty be wise (Eruditi professores), and the benefactors be generous (Largiantur donatores). The exercises conclude following the benediction, when the president's division has left the platform and the sheriff declares, "The meeting is adjourned!"

As the crowd slowly makes its way out of Tercentenary Theatre, the bells of more than a dozen Cambridge churches peal joyfully in a tradition begun in 1989. Among them, from high in the Lowell House tower, the great Russian zvon also peals. The tintinnabulation celebrates, in the words of "Fair Harvard," another successful cycle of "these Festival Rites... from the Age that is past to the Age that is waiting before."

~ Cynthia Rossano

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()