Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

|

| The sacred Hindu thread ceremony, the "upanayana," at Sri Venkateswara Temple, Bridgewater, New Jersey. |

It is precisely the interpenetration of ancient civilizations and cultures that is the hallmark of the late twentieth century. This is our new georeligious reality. The map of the world in which we now live cannot be color-coded as to its Christian, Muslim, or Hindu identity, but each part of the world is marbled with the colors and textures of the whole.

It is precisely the interpenetration of ancient civilizations and cultures that is the hallmark of the late twentieth century. This is our new georeligious reality. The map of the world in which we now live cannot be color-coded as to its Christian, Muslim, or Hindu identity, but each part of the world is marbled with the colors and textures of the whole. |

| New construction supervised by Phramaha Prasert Kavissaro, abbot at Wat Buddhanusorn, a Thai Buddhist temple in Freemont, California. |

|

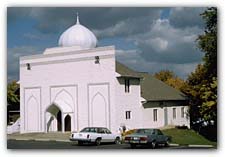

| Masjid Al-Khair in Youngstown, Ohio. |