Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

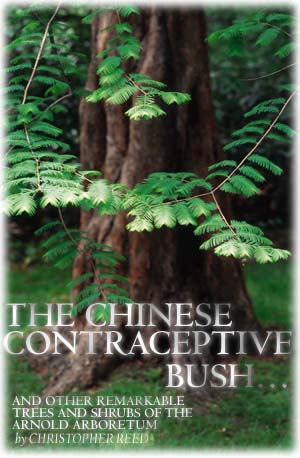

| Metasequoia glyptostroboides, DAWN REDWOOD |

A living fossil. A well-behaved mimosa. A Stewartia in camouflage. Ten characters from the kingdom of plants speak of their own wonderfulness-and of the work that goes on at Harvard's Arnold Arboretum.

Botanical Research

The puzzling fossils Japanese paleobotanist Shigeru Miki had before him were not, he decided, the remains of bald cypresses or redwoods or any other known tree. He invented a new genus, Metasequoia ("akin to the redwoods"), and put the fossils into it. Presumed extinct, Metasequoia had flourished across the Northern Hemisphere with the dinosaurs.

Miki did his naming in 1941. In that very year, a Chinese forester, T. Kan, happened upon a curious coniferous tree outside the hamlet of Modaoqi in eastern Szechwan Province, in remote, interior China. No doubt distracted by the war then raging, the Chinese did not identify their new tree until 1946, when Professor H.H. Hu, China's leading dendrologist, concluded with astonishment that it was Miki's Metasequoia. Hu sent a herbarium specimen to Professor Elmer D. Merrill, S.D. (hon.) '36, director of the Arnold Arboretum, for his examination. It was no random matter that Metasequoia came to the Arnold instead of some other botanic garden. Hu was the first of many Chinese botanists to receive graduate training at Harvard. He had earned his doctor of science degree in 1925, knew Merrill well, and admired the arboretum.

Merrill immediately provided a sufficient sum, $250, to fund the Chinese in a seed-gathering expedition for the arboretum. The seeds arrived in 1948. The press trumpeted the event, calling the tree a "living fossil." But would the fossil flourish? The arboretum planted seed in the greenhouses at Jamaica Plain and sent packets of it to other botanic gardens worldwide. Until that moment, interest in the Chinese tree had been largely botanical. No one knew that Metasequoia glyptostroboides, the dawn redwood, would have horticultural merit. It did. One of the few deciduous conifers, majestic, hardy, it offers beautiful needlelike leaves, fissured exfoliating bark, and a mightily buttressed base.

|

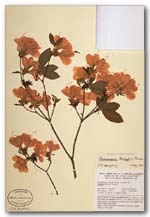

| A HERBARIUM SPECIMEN OF Rhododendron kaempferi, THE TORCH AZALEA |

Charles Sprague Sargent, A.B. 1862, LL.D. '01, was the arboretum's first director and its constant inspirator for 54 years. He conceived from the beginning that arboretum staff should go to distant places in search of plants and bring 'em back alive, as well as dried and pressed. In 1922 he wrote: "During the last forty years the Arboretum has lost no opportunity to increase the number of species of plants cultivated in the United States and Europe. Its officers and agents have continued to explore the forests of North America; they have visited every country in Europe, the Caucasus, eastern Siberia and Korea, and have studied every species of tree growing in the forests of the Japanese Empire�.Agents of the Arboretum in pursuit of knowledge and material have visited the Malay Peninsula, Java, the Himalayas, the high mountains of east tropical Africa, southern Africa, Australia, Mexico, Peru, Chile southward to Tierra del Fuego, and the Falkland Islands." Arboretum staff remain on the prowl. Under contract from the World Bank and the government of Indonesia, they are providing technical assistance in a $12 million project for biodiversity conservation and natural resource management. They are helping local botanists collect Indonesian plants in a search for anti-cancer and anti-AIDS pharmaceuticals.

Sargent himself went to Japan in 1892, where he collected many treasures later introduced into Western horticulture, among them the torch azalea, shown at right. This species, widely grown in American gardens, has flowers of a refinement

|

| Rhododendron kaempferi, TORCH AZALEA |

In 1905, John G. Jack, Sargent's right-hand man at the arboretum, went to Korea, one of the first North Americans to hunt for plants there. He returned with numerous finds, including the royal azalea, lower left. A knockout, six to eight feet tall and wide, it is one of the finest azaleas for northern gardens. Its large flowers open just as the leaves expand.

In 1906 Sargent engaged Ernest Henry Wilson, who had already been twice to China as agent for an English nursery, to go yet again for Harvard. Thus began a marvelous immigration of plants with Wilson's name on them. He went

|

| Rhododendron schlippenbachii, ROYAL AZALEA |

"Sargent's interest was always the marriage of botany and horticulture. He did both simultaneously," says Peter Del Tredici, the arboretum's assistant director for living collections. "Both disciplines are treated as equal partners here. As long as we remain true to that, we have a bright future."

Hardiness testing

When André Michaux came to America from France in 1785, he brought with him seeds of the silk tree or mimosa, Albizia julibrissin, and shared them with other nurserymen. Thomas Jefferson grew some of the seedlings at Monticello. A deciduous tree about 30 feet tall with a layered structure, A. julibrissin imparts a distinctly tropical feeling to any garden it grows in. Although the silk tree is very slow to leaf out, waiting often until late May or early June, it eventually produces fernlike doubly compound leaves consisting of hundreds of small leaflets. (Look closely at a leaflet and notice a peculiarity: its midrib lies not at the center of the leaflet, but almost adjacent to one edge.) Powder-puff pink flowers appear during most of the summer. Michaux's tree flourished throughout the Southeast, becoming a weed in fact. Today, webworms infest it, and it is often killed by a vascular wilt disease. Authorities advise against planting it.

|

| Albizia julibrissin 'ERNEST WILSON' |

|

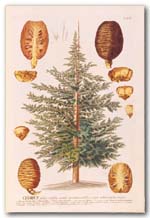

| Cedrus libani, HAND-COLORED PLATE BY GEORG DIONYS EHRET, FROM CHRISTOPH JAKOB TREW'S Plantae Selectae (NUREMBERG, 1765) |

Charles Sargent wanted badly to grow the cedar of Lebanon, that stately, umbrageous ornament of English estates. When the psalmist wrote that "the righteous�shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon," he was talking big, a hundred feet tall or more with wide-spreading branches and a massive trunk. The seventeenth-century silvaculturist John Evelyn wrote of one in the Holy Land "of a prodigious size, twelve yards and six inches in the girt."

But the cedar of Lebanon wouldn't live for Sargent although he tried and tried. Then he learned that it grew at 12,000-foot elevations in the Taurus Mountains of Turkey. He commissioned a botanist from Smyrna to go to the mountaintop. Seed he collected produced Cedrus libani variety stenocoma, reliably hardy in Boston, a little more upright and stiff than the descendants of those trees on the hills of Palestine.

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Harvard Magazine · 7 Ware Street · Cambridge, MA 02138 · Phone (617) 495-5746