Despite rainy weather and the mounting academic demands of the fall semester, students, staff, and faculty trekked across the river and the HBS campus for a symposium on the state of democracy at Harvard Business School (HBS). The event took place inside Klarman Hall, the new auditorium and convening space named after benefactors Seth Klarman, M.B.A ’82, and his wife, Beth Klarman, president of the Klarman Family Foundation.

Opening the dedication ceremony, HBS dean Nitin Nohria spoke about the hall’s unique power to spark the Harvard community’s collective imagination and make amazing new formats of teaching and learning possible. “It’s a space that has all the great elements of our classrooms, with little separation between the teacher, presenter, students, and audience,” Nohria said. “Already, I’ve had a faculty member ask how large an M.B.A. course they may be able to offer here.” Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker ’79 later added, in his brief dedication speech, that spaces like Klarman Hall provide valuable opportunities for face-to-face discussions about opposing viewpoints, something many Americans increasingly have little time for.

Several speakers emphasized the donors’ dedication to giving back to what Beth Klarman called “a community of friends” at HBS. Initially, the gift had been intended to support a center for value investing, but upon learning that the campus had little space for another center, the Klarmans decided to pursue a vision for a technologically advanced, modern building that could comfortably hold an entire M.B.A. class (currently around 940 students). “It’s never been more important for people to come together to listen, to open our minds, and to learn,” said Seth Klarman.

“The world that we live in is not perfect,” President Lawrence S. Bacow pointed out in his remarks. “If you don’t think the world is perfect, the only way it gets better is if good people work to repair it. And this, Seth and Beth have done throughout their careers and throughout their lives. If you look throughout Boston, you will see the fruits of their time, and their effort, and their generosity.”

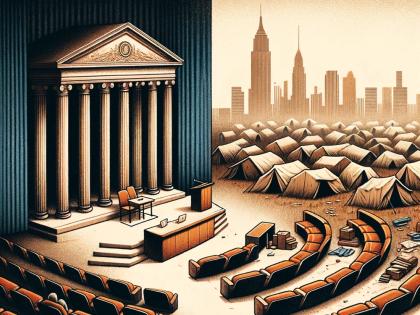

“An Atrophying Culture of Democracy”

Following the dedicatory speeches and ceremonial ribbon-cutting, Cherington professor of business administration David A. Moss began the symposium on democracy by challenging the popular belief that Americans today are experiencing an unprecedented period of political conflict and partisanship.

“Throughout history, political conflict has been a vital source of new and innovative ideas,” he said, pointing to a notable historical example: the intense partisan conflict during the early nineteenth century actually contributed to a period of great economic progress which led lawmakers in New York state to invent modern banking regulations and a workable system of fiscal control eventually adopted by every other state in the country. “Political conflict,” he declared, “is vital for progress, just as competition is essential for innovation in the economic realm.”

Moss encouraged the audience to critically examine and characterize today’s political unrest as either productive conflict––like that in New York state during the early nineteenth century—or destructive conflict—like that between North and South over slavery that ultimately led to the Civil War. “Political conflict has typically proven constructive when there is a strong, overriding, abiding commitment to democracy itself, cutting across all of the conflicting interests and parties. A strong culture of democracy is really the glue—maybe the only glue—that holds Americans together,” he said. “When the commitment to democracy has faltered—as it did leading up to the Civil War—that’s when political conflict becomes dangerous.”

Despite the natural human inclination to indulge in it, Moss warned against “political hypochondria”—the tendency to erroneously assume that American democracy is always teetering on the brink of collapse. Yet he then drew a troubling conclusion, supported by recent survey data from Gallup and other pollsters, showing a decline in Americans’ faith in one another and, as a result, in democracy as a whole. “Unfortunately, I think there is mounting evidence that something really important has changed,” he said. “I wish it was as simple as heightened partisanship or even a stagnant party system, or too much money in politics. I think the evidence suggests a far more fundamental problem, namely that our culture of democracy has atrophied over recent decades. This leaves us vulnerable.”

To inject life and trust into American democracy once more, Moss pushed for the introduction of comprehensive civics curricula in public schools. For example, his own course at HBS, “The History of American Democracy,” uses the case method to “introduce students to different critical episodes in the development of American democracy, from the drafting of the Constitution to contemporary fights over same-sex marriage.” The class sessions “encourage students to challenge each other’s assumptions about democratic values and practices, and draw their own conclusions about what democracy means in America.”

“Clearly, Politics Doesn’t Work The Way Schoolhouse Rock! Said It Did”

Following Moss’s presentation, Lawrence University Professor Michael Porter took to the stage with Katharine Gehl, former CEO of Wisconsin-based Gehl Foods, to discuss their research about the shift in American competitiveness, from both a social and economic perspective.

According to the 2018 Social Progress Index, which Porter developed in collaboration with Sarnoff professor Scott Stern of MIT’s Sloan School of Business in 2015, the United States lags far behind when compared to the other 35 member-nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: it is thirty-fifth in maternal mortality, thirty-fifth in secondary-school enrollment, and twenty-eighth in property rights for women. “Not only are we no longer a leader on the social agenda, but our performance is actually continuing to erode,” Porter said. “It’s eroding in some of the areas we cherish the most: opportunities, rights, and religious freedom.”

To understand why American democracy has continuously failed to address such issues, Gehl argued, requires recognizing that the blame lies with the so-called American political-industrial complex, or the partisan duopoly system. “Partisan primaries and partisan gerrymandering feed the duopoly,” she said. “Clearly, politics doesn’t work the way Schoolhouse Rock! said it did.”

Gehl anchored her discussion on a recent Gallup survey indicating that 61 percent of Americans today feel that a third party is needed to help move the country back toward a position of international leadership and progress. “With this much customer dissatisfaction,” she declared, “if politics were a business, some entrepreneur, maybe someone from HBS, would see it as a phenomenal business opportunity and we would see a new entrant competing to deliver what those customers wanted. But that doesn’t happen in politics, because the parties work really well together in one particular way: to rig the rules of the game to protect them from new competition, they erect huge barriers to entry. Said another way: politics isn’t broken, it’s fixed.”

Given what Porter and Gehl referred to as “no new real competition” to the existing duopoly since the Republican party was founded in 1854, the two said the current social and political situation calls for a reform strategy to “change the rules of the game.” This would involve instituting counterweights to money in politics, re-engineering the legislative machinery to eliminate partisan control, and allowing ranked-choice voting in general elections across the country. “The parties don’t want to compromise, because if they compromise, they alienate their core customers who provide all the resources and money, who show up to those primaries and regularly vote on one side or the other. The parties don’t have to deliver for the average voter to stay in power. They can not get anything done—and still stay in power and not bear the consequences.”

“Why Are We Here?”

For the remainder of the symposium, former Harvard Law School dean and current 300th Anniversary University professor Martha Minow moderated a panel discussion about the state of American democracy, followed by a fireside chat among Dean Nohria, Seth Klarman, and Jamie Dimon, M.B.A. ’82, chairman and CEO of J.P. Morgan Chase. Throughout both discussions, points were made about the decline in civic engagement and education—panelist Bret Stephens, an op-ed columnist at The New York Times, said that he had begun to educate his own children on the basic tenets of the U.S. Constitution after recognizing the shortcomings of the American public school system. Fellow panelists Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, and Michael Klarman, Kirkland & Ellis professor of Law (and brother of Seth Klarman), talked about the dangers of encroaching on the constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech, as well as of the impacts of increasing attempts at censorship and manipulation aimed at the so-called mainstream media. “Democracy is in a state of recession,” said lecturer on government Yascha Mounk.

At the fireside chat, the conversation turned to the effectiveness of capitalism and the role it has played in the current state of American democracy. “I think we can make the case for capitalism,” Seth Klarman said. “I think we can say that capitalism has lifted billions of people out of poverty…and the challenge now is not to move to a different system where we’d maybe more equitably divide a smaller pie, but rather to have the pie be as big as possible.” Later, Dimon shared his optimism that business leaders—including members of the HBS community from within the audience—can and, in fact, should play a critical role in rebuilding faith in capitalism by creating jobs, and by pushing to roll back personal tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans. When asked about how empathetic, experienced business leaders might be uniquely qualified for public service, Klarman said that the current political system is “deeply broken” because it presents an “obstacle course” to getting elected for anyone who hasn’t been working in politics for his or her entire life. “Yelling about millionaires and billionaires is just a different kind of identity politics,” he pointed out. “It’s terrifying—there are good millionaires and bad millionaires.”