Figuring that “day-trading my stock portfolio was not the best use of my time,” former banker Aaron MacDougall ’94 chose instead to open Broadsheet Coffee Roasters, a specialty coffee house in Cambridge that aims to educate as it caffeinates.

MacDougall “curates” the raw green beans—mostly from growers in Ethiopia, Peru, and Guatemala—and convection-roasts them in the gleaming and efficient Loring S-15 that sits behind a rope like a museum piece in the Kirkland Street café. It perfectly browns coffee that’s sold in bags or brewed for customers (using water thrice filtered and re-mineralized in the basement) by discerning baristas. “What we’re really fighting here is the fast-food mentality of the United States,” says MacDougall. “Across the country, coffee equals ‘caffeine-delivery mechanism’ for the working person. We’ve been trained to just dump in the cream and sugar and not even taste the coffee.” He’s trying to communicate the “value proposition” of fine coffee: to help consumers think differently and not waste their “caffeine capacity on something that’s inferior.”

Aaron MacDougall

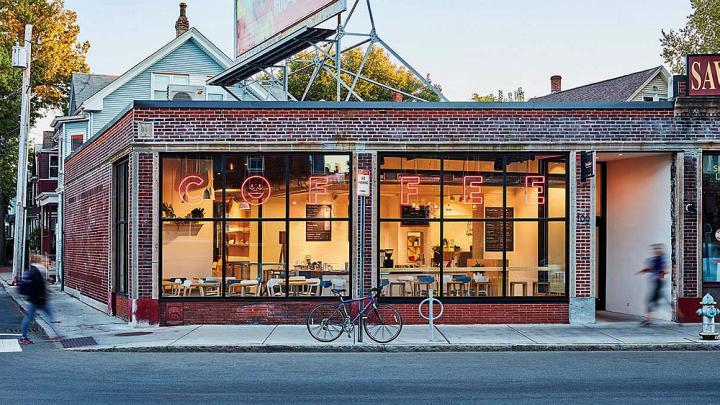

Photograph by Katherine Harrison/courtesy of Broadsheet Coffee Roasters

A 12-ounce brewed cup costs from $3.25 (plain) to $5.00 (vanilla latte, mocha); a 12-ounce bag of roasted beans is $18 to $22. When asked about what some patrons see as steep pricing, MacDougall counters: “But I always think, ‘Why is it so cheap?’”

Consider the labor-intensive process of bringing coffee to the market, he explains: the cultivation, hand-picking, sorting, and cleaning that mostly occur in high-altitude, rural areas that are hard to reach; then add transportation costs. His raw coffee is a “dramatically” higher grade than any Starbucks offering, and costs customers only about 50 cents more per cup. Like fine wines, he points out, specialty coffees have distinctive nuances. Describing two varieties from Ethiopia, which holds near-mythic status among serious coffee-drinkers as the origin of the indigenous arabica coffee shrubs, he says, “The best-selling Qonqona brew tastes of rich, dark cherries,” whereas “the classic Yirgacheffe Kochere is a lighter roast with “a strong bergamot, herbal note.”

Broadsheet also customizes grinding, brewing, and roasting. “Starbucks uses super-automatic machines; they just press a button and out it comes. They have built-in grinders and their espresso-makers are notoriously crappy,” he adds. “And we use a steam wand, which forces hot steam into the milk, creating micro-foam [versus the frothers at Starbucks], and milk from a local farmer, too.”

MacDougall spent 17 years in banking, ultimately as a managing director in the global markets division of Deutsche Bank in Tokyo. In starting Broadsheet, he considered the paths of some peers. “I know a lot of people in their forties and fifties who were in the finance industry and are now doing nothing, or going through the motions, doing more of the same—really bright, really capable—and they’re managing their portfolios all day, watching Netflix, and trying not to pay taxes,” he says. “I just had a negative reaction to the money making money.” Instead, he sees his café (which also sells excellent, house-made baked goods, along with breakfast and lunch fare) as a means of “doing something fun that I love, and building something: employing people, creating community.” He enjoys applying his banking acumen to the specialty coffee industry (understanding relative value, and global and commodities markets, for starters), as well as to running a small business.

But his infatuation with java began only after he’d left finance—and moved with his wife and their young son (then suffering from myriad allergies) to Hawaii. It was a purely sensuous pursuit: “In Hawaii I could go into the mountains and pick coffee with friends and bring it home and roast it myself,” he says. Analytical and detail-oriented by nature, he soon found a local coffee-roasting mentor and began experimenting, testing various beans and temperatures, learning the art and science of extracting and honing flavor. “My wife told me, ‘This is so much better than any other middle-aged-guy hobby.’”

Five years ago, the family moved to the mainland United States and settled in Brookline, closer to MacDougall’s parents, and he sought out the local specialty coffee subculture, attending seminars and trainings at the Somerville outpost of Counter Culture Coffee company. In 2015, he sat through a six-day exam period to become a certified Q-grader (“Like a master sommelier, but for coffee,” he says; “there are only maybe 300 to 350 of them in the United States”), entitled to officially evaluate the quality of coffees.

Here’s his quick lesson on grading: green arabica coffee is scored on a 100-point scale; anything below 80 points is priced off of the commodities futures markets and sold in grocery stores, although the top-shelf brands at big coffee chains rate as high as 84. Most lower-grade arabica coffee comes from Brazil and Colombia, while robusta (which MacDougall calls “crap”) is from Vietnam; and the specialty coffees are grown largely in East Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi) and Central America (Guatemala, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Panama); those above 86 points are generally produced in micro-lots of under 10,000 pounds. Broadsheet’s beans, he adds, are scored from 86 to the low 90s: “Coffees over 92 points are unicorns, there are almost none, and often go for hundreds of dollars a pound raw.”

MacDougall now puts his connoisseurship to the test. He won the Genuine Origin Coffee Project’s debut “Roast and Go” competition in 2016, and last year placed fifth in the United States Cup Tasters Championship (against experts from companies like Green Mountain Coffee Roasters and Blue Bottle). Contestants strive to be the fastest and most accurate in identifying the odd one out of three cups of coffee. If that sounds easy, he says, it’s not: “They try to select coffees that are very similar. You can have two coffees from the same farm, but one’s grown on one side of the plantation, and the other, on the other side.”

Appreciation of fine coffee (and the price point that often goes with it) already exists in Los Angeles and New York City, he says, and is slowly emerging in Greater Boston, through the work of companies like Counter Culture and the Acton-based George Howell Coffee. And MacDougall concedes that he was once as naïve as anyone else: “Before I got into this, I thought of a coffee bean as a grain of rice: every one was perfect. And it couldn’t be farther from the truth.”