One hundred years after Gutenberg mass-produced his first Bibles in Germany, book printing emerged in eastern Europe. Ivan Fyodorov was working as a deacon in Moscow’s Kremlin when he began printing church texts, starting with Apostol in 1564. Later, he would move to Lvov, at the western edge of Ukraine, where he published the earliest printed books produced there. The only remaining copy of his 1574 Bukvar, or primer, for teaching children to read Old Church Slavonic, the language of Eastern Orthodoxy, is at Houghton Library.

The early books were largely liturgical; later, the works of Ivan Kotliarevsky and Taras Shevchenko, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century thinkers who wrote in Ukrainian, not Church Slavonic, would give form to a Ukrainian national culture. Their first editions can be viewed at Houghton, too, part of a collection spanning thousands of volumes across Harvard’s libraries—one of the largest Ukrainian-language repositories in the world. Scholars from Ukraine visit often, seeking books they can’t find at home, says Olha Aleksic, Jacyk bibliographer of the collection.

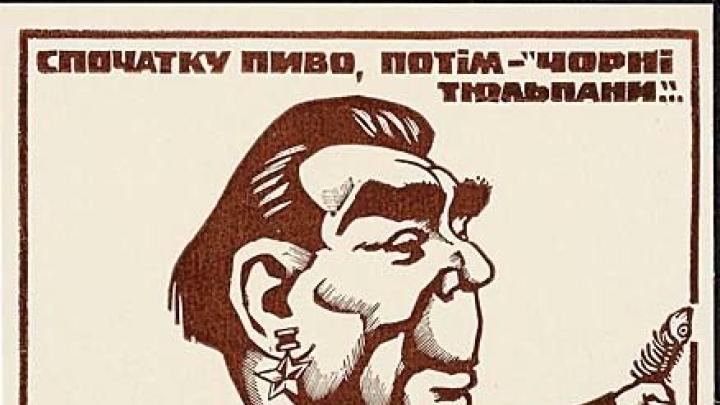

A political cartoon from the collection’s contemporary holdings, housed at Widener, displays a pompous-looking Leonid Brezhnev, with a mug brimful of beer in one hand and a stockfish in the other. The caption warns: “First beer, then black tulips.” Signposts on either side of him point to Prague and Kabul, alluding to the Soviet invasions of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Afghanistan in 1979. When the cartoon was printed, right before the Soviet Union’s collapse, Ukrainians would have recognized the “black tulips” as the planes that carried the dead bodies of Soviet soldiers back from Afghanistan. In the cartoonist’s rendering, tying Ukraine’s fate to the Russians would bring endless war for an unknown cause. Brezhnev is driven by drunkenness and ego, not by human rights, justice, or even communism.

A hard hat worn by demonstrators during the Euromaidan protests displays chestnut blossoms symbolizing Kiev.

Image courtesy of the Ukrainian Research Institute Reference Library

To westward-looking Ukrainians, Russia’s yoke still looms. On a visit to Harvard, activist Yulia Marushevska, whose video I Am a Ukrainian went viral during the 2013-2014 Euromaidan protests, donated a hard hat from the demonstrations to the Ukrainian collection. Covered in bright chestnut blossoms, a symbol of Kiev, the hat and others like it were worn by demonstrators after the Ukrainian parliament banned their use at protests. Says Aleksic, “Thousands of people showed up in the streets wearing hard hats, helmets, colanders on their heads in defiance of the law.”