“Lucifer’s car was towed,” someone announced to the room—they’d have to start without him. The three Fates reviewed some new choreography; by the piano, Persephone, a tall soprano, nervously rolled a pencil between her fingers as she approached a tricky high note. “My blood rubies, centuries old,” she sang, her eyes darting to the composer for his reaction. He gave a thumbs-up. When the devil finally arrived with breathless apology, the workshop cast of Rev. 23—all graduate students in the New England Conservatory’s opera program—prepared to take act one from the top. The curtain rises: the apocalypse is over. Heaven reigns on Earth. “Don’t get bogged down by plot issues,” the director reassured them. Gesturing toward the colleagues seated behind him, he added, “That’s their problem.”

Cerise Lim Jacobs

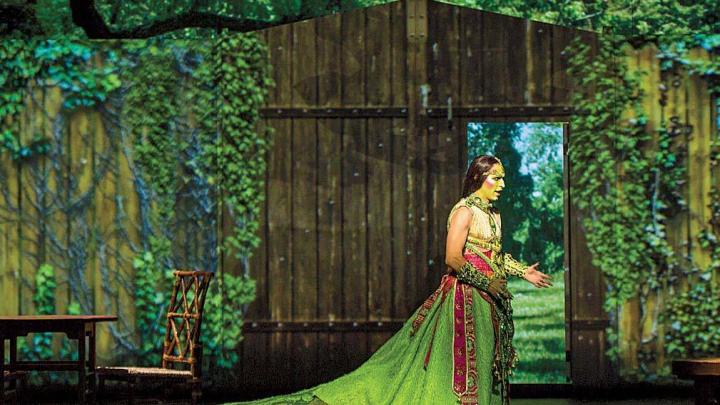

Photograph by James Daniel/Courtesy of Beth Morrison Project

Mainly, plot fell under the jurisdiction of librettist Cerise Lim Jacobs, J.D. ’81. Rev. 23, an imagined sequel to the Book of Revelation,begins when Lucifer conspires with Hades to destroy the power plants that enforce endless, paradisiacal summer. Later, they enlist Persephone and Sun Tzu in their rebellion; sometime in act two, Adam and Eve show up, as does the archangel Michael. Jacobs, along with composer Julian Wachner and dramaturg Cori Ellison, watched as the singers waded through this madcap, overstuffed plot. In workshop, “We find out whether something sounds stupid when it’s sung,” says Jacobs, “or if something stinks. Everything looks good on paper, sounds good on paper—but there’s nothing like putting it on its feet.”

A freewheeling approach to different cultures is typical of Jacobs’s work, which is fantastical and afterlife-obsessed. Her libretti star characters from Chinese legend, with dream sequences set in Sumerian myths and lines borrowed from King Lear and The Song of Songs. This hodgepodge reflects her upbringing in Singapore, with its stew of faiths and languages. Jacobs’s Cantonese-speaking parents initially sent her to a Chinese school, where she learned Mandarin; then they had second thoughts (“They were afraid I would be converted to this horrid little Communist in their midst”), and switched her to a Methodist missionary school, where she learned hymn singing and Bible study. The family regularly celebrated Hindu festivals and the end of Ramadan with their Tamil and Malay friends, Jacobs recalls. And: “We watched Chinese opera religiously, every Sunday, at my grandmother’s house.” The genre differs from Western opera not just in musical scale but in overall duration, she points out: a single work can go on for days, with attendees eating throughout. Jacobs attempted to recreate a version of that experience with her Ouroboros Trilogy, which audiences could watch in all-day musical marathons at Boston’s Cutler Majestic Theater this past September. “They do not allow you to bring in food,” she laments. “Munching on French fries as you’re watching—it wasn’t possible. But if it were, I would want that!”

Ouroboros follows a snake demon and her besotted companion as they’re reincarnated at three different points in time. In each of the operas—Madame White Snake, Naga, and Gilgamesh—a dogmatic man of religion becomes their adversary, and other humans get tragically caught up in the conflict. Spanning fictional eons, the complete cycle runs a little over five hours, and began as a lark. Having practiced law for more than two decades, Jacobs was three years into retirement when, in 2005, she began to write a song cycle as a birthday present for her music-loving husband. Pushed by his questions about the characters and plot, she expanded it into a full-length work. Potential composers balked at the prospect of writing something that would be performed only in the family’s Brookline living room, so Jacobs cold-called Opera Boston. Madame White Snake premiered there in 2010, directed by Robert Woodruff (former artistic director of the American Repertory Theater); its score, by Zhou Long, won the Pulitzer Prize for music in 2011.

Now, Jacobs is intent on building an oeuvre for herself. “I have this master plan to commission and produce one new work a year for the next five years,” she says, matter-of-factly. Ouroboros is her grand epic; Rev. 23, premiering in September 2017, will be her comic opera, with a cast small enough to travel. (She has also finished drafting the next work, Permadeath, which will involve an augmented reality, videogame component.) Jacobs, who often accessorizes with a purple, gargoyle-shaped backpack, has an elfin appearance and whimsical imagination. But her undeniable, entrepreneurial energy brought composers like Long, Paola Prestini, and Scott Wheeler aboard her flights of fancy: her can-do spirit is matched by will-do drive.

Collaboration does require compromise. Days in, the NEC rehearsals for Rev. 23 foundered amid the cast’s confusion about character motivations and narrative twists. The production team had an all-day meeting to brainstorm. “I needed a breakthrough,” says Jacobs. They lost a subplot involving angelic wings, but kept another about the Book of Life; they added more comedy. “As a lawyer, you’re used to being edited, people arguing against you,” she says, with a sigh. “Trying to make you better, you know.” Occasionally, she adds, “I have to step back and say, I’m at the end. I’m at the final phase of my life. I need to remember why I’m doing this. I’m doing it for the love of it. For the fun of it.”