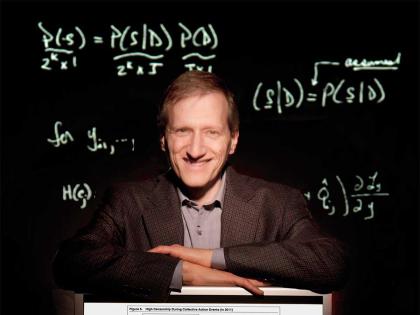

The only props in The Lion, the critically acclaimed musical by Benjamin Scheuer ’04, are the chair he sits on and six gorgeous guitars. Among them, there’s a gentle 1929 Martin, an electric Gibson that growls, and a stylin’ Froggy Bottom H-12, which Scheuer got as a thirtieth birthday present.

But the two most important instruments Scheuer has ever played are not on stage with him. The first is a toy banjo that his lawyer father made for him out of the lid of a cookie tin, some rubber bands, and an old necktie for the strap. Scheuer played it alongside his father on the front porch, mimicking his finger strokes. The second instrument is the guitar his father played, which the teenage Scheuer inherited after a sudden brain aneurysm killed his father and sent his world into chaos.

Told mostly through whimsical and poignant songs, The Lion traces Scheuer’s quest to understand the parts of his father that he never could as a boy: the manic rages, the disappointment in his son, and the discouragement regarding music as a career. It’s also the story of the son’s attempts, across nearly 20 years, to reconnect with the father he loved, the man who taught him the joy of music. “I don’t know that I wrote this show in order to come to grips with my father’s death,” he says. “I think I needed to understand my father’s death in order to write the show.”

On stage, Scheuer sports a wide boyish grin, a well-tailored suit, and floppy hair. He both charms and disarms the audience with his intensely personal story (told while transitioning among the six guitars). Born as a few songs the New York singer-songwriter had strung together while playing Greenwich Village coffeehouses and bars, The Lion, now a 70-minute solo show, has been praised by The New York Times and the Huffington Post, and has won London’s Offie Award for Best New Musical. Scheuer, The Boston Globe wrote, “...can pluck the audience’s heartstrings as skillfully as he does his guitar.” The show, which had earlier runs off-Broadway and at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, began a one-year, five-city tour in August at the Merrimack Repertory Theatre in Lowell, Massachusetts, before traveling to Milwaukee, Rochester, Washington D.C., and Pittsburgh. The animated music videos for two of its songs have won prizes at the Annecy Film Festival, The Crystal Palace Festival, and the British Animation Awards.

Scheuer began delving into his father’s death about three years ago, when he released an album, The Bridge, recorded with his band, The Escapist Papers. Nervous about performing the songs live, he decided to write down a script that would explain the genesis of his lyrics to the audience. “I was trying to make the banter as good as the songs,” he says. “Then I realized that the stories that I’d started to tell between songs demanded better or different songs, so I kept writing new ones and more new ones. And the songs that were on The Bridge sort of fell away, and I began writing The Lion.”

Soon after, in 2013, Scheuer met Sean Daniels, who is now the Merrimack theater’s artistic director. They formed a fast friendship and began shaping The Lion into a full musical, developing an outline for the show based on mythologist Joseph Campbell’s theory of the “Hero’s Journey.” By the end of the week, the two had written the beginnings of many of its songs, including “Cookie Tin Banjo,” “When We Get Big,” “White Underwear,” and the deeply emotional “Dear Dad.”

“Sean said to me, ‘Hey, you like to write postcards. Have you ever written a postcard to your late father?’” Scheuer recalls. “Then I started crying, and Sean got really concerned, and went out and bought the most expensive bacon he could find and cooked it for me.” Inspired by Daniels’s prompt, Scheuer wrote “A Surprising Phone-call” as an imagined conversation between his mother, Sylvia, and his late father. “Will you wish a very happy birthday to the boys? / They must be big at 26 and 28,” Scheuer sings. “Now I hear that each of them is playing in a band. / I guess the drum-kit and piano and guitars were really tempting fate. / Sylvia, you helped them grow. / Please forgive me, love. I never meant to go.”

Playing himself at age 14 in another scene, Scheuer expresses his anger at not being allowed to attend a much-anticipated band trip to Washington, D.C., because of a poor grade in math. In response, the teen pins a note to his father’s door, calling him “the kind of man that I don’t want to play music with, the kind of man that I don’t want to be.” Scheuer and his father didn’t speak for more than a week—and before they could reconcile, his father died.

The show also chronicles other major life events, like the first time Scheuer fell in love, and his diagnosis of stage IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2011. In song, he narrates the process of enduring chemotherapy treatments, and the subsequent weight gain, hair loss, depression—and ultimately, a new outlook on life.

“My oncologist told me that as I got better on the inside, I was going to look worse on the outside,” he says. “I was horrified and fascinated by this dichotomy, and I thought how interesting it would be to make a visual piece of art out of this.” And so, once a week during his illness, photographer and friend Riya Lerner photographed Scheuer with a medium-format Rolleiflex from the 1970s, resulting in Between Two Spaces, a book of 27 black-and-white photographs accompanied by text from his journal. In the book, Scheuer writes:“You can take something, whether it’s an illness, or emotional hardship, or a breakup, and create something out of that: it doesn’t have to be this isolated event that happens to you, but becomes a way for you to gain control of it, and make it into something new.”

Daniels—who had lost his own father a year before meeting and collaborating with Scheuer—says that working with someone unafraid to examine loss was both terrifying and exciting. “What I always like to say is that Benjamin is dangerously honest. It’s so comforting when somebody just goes ahead and tells the truth.”

In The Lion, some of that truth is truly heartwarming—“My father has an old guitar and he plays me folk songs,” Scheuer sings in the show’s opener. “There is nothing I want more than to play like him”—and some is not, as when Scheuer recounts those fits of rage: “I ask my friend, ‘What do you do when your dad breaks your toys?’ ” Scheuer recalls in one scene. “And he looks at me like I’m insane.”

Ultimately, for Scheuer, “Songwriting is a way for me to understand what’s going on in my own mind and to be able to share those things with other people. To be able to take the worst things in my life—the things that I feel make me feel disconnected—and use them as connection is just amazing alchemy.”