I’m running an experiment on the first floor of Lamont Library. With my right forefinger I de-shelve C.S. Lewis’s slender book of criticism on John Milton and flip to its first page to check a quote. Milton “is writing epic poetry, which is a species of narrative poetry, and neither the species nor the genus is very well understood at present.”

The symptoms that led Lewis to this diagnosis of higher illiteracy are abundant, he assures me; they speckle the page like a rash and afflict, most prevalently, secondhand books: “In them you find often enough a number of not very remarkable lines underscored with pencil in the first two pages, and all the rest of the book virgin.”

Continuing the experiment, I move one shelf over and grab the frowziest-looking copy of Paradise Lost in sight (for my purposes, down-at-heel means ideal). But in flipping through its pages, it seems the tome I’ve chosen is healthy: there’s not a single annotation in sight.

As the critic sees it, books, and the sentences that comprise them, function musically. The words and passages support one another. They should be allowed to resonate freely. Effects are slowly developed over long passages; a pedantic view—exemplified by the isolation of single lines or words—curtails these effects, and dampens the book as a whole.

This is no incisive or newfangled conception of reading—in fact, it’s really as basic as such conceptions get, more like natural, instinctual knowledge—but I feel it’s often ignored or forgotten today, perhaps precisely because it is so obvious.

A few feet away from me, at desks, in wingback chairs, are students who are reading, apparently with varying levels of success. Some of their faces are squinched in attempted concentration, while others are blank, as if they’ve given up.

I look down at the pristine copy of Paradise Lost in my hand and realize that its purity doesn’t necessarily signal a win for our critic.

Blank pages may mean ignorance, or frustration, as well as immersion.

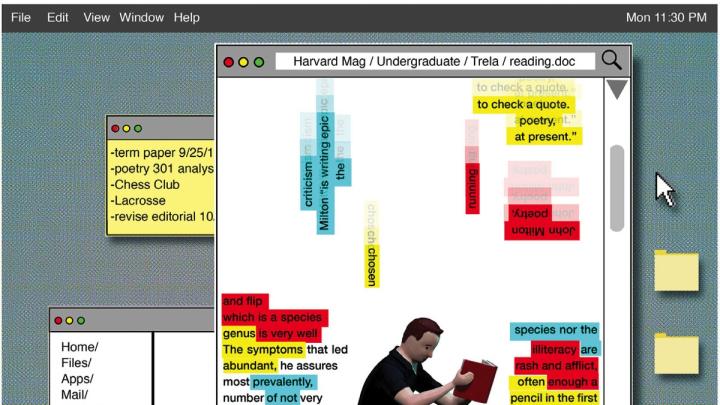

This is routine: I open a Google doc and see the draft of an article bruised black, blue, and red by annotations. To the right, a mesh of comments, emendations, and tracked changes cascades down the screen, while up above a multicolored set of blinkers tells me who else is currently viewing the document.

I find it’s hard not to sigh or groan or chew nervously at my lower lip when confronted by this welter of collaboration. The cursors move discursively, frantic as flies: words are excised and commas injected, proper nouns capitalized promptly. Before I’ve had time to orient myself, to take stock of the text’s essence, the document has dissolved into a protean shimmer of minute changes, reconstituted in a thousand small ways.

For basically anyone unsworn to Luddism, the insinuation of digital collaboration into modern college life is a fait accompli. Generally with faculty blessing, we students have begun to share everything—essays, study guides, and drafts of creative writing—crowdsourcing the production of prose. We fill margins with half-jokes and our particular grammatical prejudices, contributing, in bits and prods, to a communal text. And all of this we do eagerly, hungrily, as if we’ve stumbled upon an unimpeachable boon.

And yet, for me, this phenomenon has always remained linked to a vague anxiety; though I can’t put my finger on the thing precisely, something about digital collaboration has always struck me, instinctually, as inimical to the way we ought to read and interact with texts.

The longer I’ve been at Harvard, the harder I’ve found it to engage in the calm, deliberate, sustained reading—unbroken, even, by the act of annotation—that Lewis championed. If I’m trying to read soon after interacting with a Google doc, the task becomes even harder; my eyes and mind, adjusted to a more frenetic pace, to a type of reading that is in a very real sense a brand of multitasking, flitter about nervously, struggling to light on individual words, incapable of easing into a measured rhythm.

The problem isn’t simply that I can’t focus. It’s that, in a way, I don’t want to focus. When compared to the high-paced, noisy causerie of digital collaboration, the solitary act of reading a book can begin to seem—and this is a painful word to write—boring.

Even worse, when compared to the ebullient camaraderie of digital collaboration, the ordinarily pleasant and reassuring solitude of a tête-à-tête with a physical book can begin to feel a little like loneliness.

When I come back to printed books after swimming in the phosphorescent shallows of a screen, I have to assure myself that this is in fact a way of reading. I have to convince myself again of the value of the old routine: clock faces occluded so I don’t worry about the time; my feet up, my back curved, my chin downturned; a fan running, or the light just right on the page. I have to mollify my overexcited nerves and set about consciously remembering how to act as the sole reader of a text. The rituals help, of course; they remind me that I’ve read like this before. That I’ll probably do so again.

And I always do remember, in the end. But it’s still a shame I have to.

If you’ve got the time, you can register for an account and submit a request and end up on a Friday morning in Houghton Library’s reading room with a two-volume facsimile of a fifteenth-century Flemish illuminated manuscript (though given this description, general interest might be a limiting factor as well).

On the facsimile’s first page—a glossy blankness—the book’s previous owner has scribbled the following: “property of V. Nabokov,” and beneath that, “butterflies identified by him.”

The manuscript, as I discovered on just such a Friday morning, is primarily interested in hagiographic imagery: Saint Veronica displays a cloth on which the shadow of Christ’s face is imprinted; Saint Anthony Abbot walks in the wilderness in the company of wild beasts.

But Nabokov, the inveterate literary trickster, has eyes only for the butterflies.

His indelicate scrawl, pressed into the page by what, it seems, had been the fine nib of a mechanical pencil, provides their scientific names: Issoria lathmia, Vanessa atalanta, Abraxas grossulariata. Occasionally a question mark appears next to a specimen, perhaps because the writer has been stumped, or perhaps (and this is more likely, as the marks are quick and cruel, almost sardonic) because the manuscript’s illuminator has whimsically and irresponsibly confected from stray colors and patterns a chimerical species.

On this Friday morning, I’m absorbed in my inspection of the manuscript. The reading room is comfortable and quiet, the air the perfect temperature and the light the perfect lambency to facilitate immersive reading.

On the few occasions that I do glance up, I can’t help but notice that there are no other undergraduates in the reading room. The desks are peopled by old men with frosty beards and willowy women in muted dresses; they inspect piles of letters and yellowed tomes with crazed leather bindings. The room is peaceful. The sibilance of turned pages rises occasionally out of the silence.

The thought occurs to me that I’m quietly reading the products of a quiet reading, emulating the very way Nabokov must have sat, the way he must have focused, his brow curled and eyes poised.

This, too, is a form of collaboration, albeit silent, protracted, and completely voluntary. I can consider the previous reader’s presence if I want to—it is not forced upon me. Likewise I can ignore his annotations, the sediment of his prior perusals.

I feel strange pondering what must have been Nabokov’s own thought process while inspecting this manuscript. He was, after all, a master of literary mystification, and so it’s odd to find him impugning the playful creation of new breeds of butterflies that exist only in, and as, art.

He must, I assume, have fallen so fully into his reading that the whole vast mechanism of his strong literary opinions and wonted modes of analysis fell away. In their absence, a very small and ardent aspect of his mind assumed complete authority. He must have read selfishly, passionately, and without a thought for anyone else.

After a while my phone buzzes (an alarm; an appointment) and I stand up to leave and realize, to my pleasure, that I’ve been doing just the same.

A little bit later, I return to my room. There are many things I need to read: novels, tracts, monographs. They’re stacked on my desk, passive as bricks.

Sometimes I feel a breed of dread when I think of the reading I’ve got to do. I worry if I’ll be able to focus; I’m afraid that the pages and the words they bear will swirl into nonsense like the symbols and signs of an abstruse theorem.

Trained by the screen to consider the gazes of others, to react quickly and decisively to their smallest suggestions, I worry that they’ll follow me into the book, that I’ll hear their mutterings while I pick my way through befuddling syntax.

And of course, this feeling’s worse today. I’m certain I’ll have the shade of Nabokov staring over my shoulder.

But then I remember that he read alone, and right now my room is quiet and the fan is slued in my direction, and the light’s coming nicely through the window.

I feel very alone.

He probably wouldn’t have cared.