People socialize online more than ever: posting photos on Instagram, job-hunting on LinkedIn, joking about politics on Twitter, and sharing reviews of everything from hotels to running shoes. Judith Donath, a fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, argues against using real names for most of these Internet interactions and relying instead on pseudonyms.

A made-up handle is essential to maintain privacy and manage one’s online identity, she says. Her new book, The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online (MIT Press, 2014), also contends that well-managed pseudonyms can strengthen online communities, an idea that contradicts the conventional wisdom that fake names bring out the worst in people, allowing “trolls” to bully others or post hateful, destructive comments without consequences. Real names, such thinking goes, keep online conversations civil.

But Donath often uses a pseudonym online, not because she wants to “anonymously harass people or post incendiary comments unscathed,” as she explained in a commentary published on Wired.com this spring, but because she prefers to separate certain aspects of her life. In the age of Google, a quick search of a person’s name gathers everything he or she has posted under that name, from résumés to college party photos. As a public figure who studies how people communicate online, Donath’s academic writing can be found online under her real name. But when she writes product reviews on shopping sites such as Drugstore.com, or restaurant reviews on Yelp, she might use a pseudonym. “I would like to be known online for what I write,” she says. “I don’t necessarily feel like I need to be known for what I’ve been eating.”

Donath stresses that using a pseudonym is very different from posting anonymously. “The difference between being pseudonymous and being anonymous is history,” she says. “For something to truly be a pseudonym, it has to have some kind of history within a particular context,” such as how many times the person has posted on a site, the topics he or she comments on, and what he or she has said. (Such details might expose malicious users or instances of “astro-turfing”—the practice of hiring writers to seed the Web with comments supporting a specific view on controversial topics. Posts from commentators whose contributions are limited to a single topic, such as gun rights, might be read with particular skepticism.)

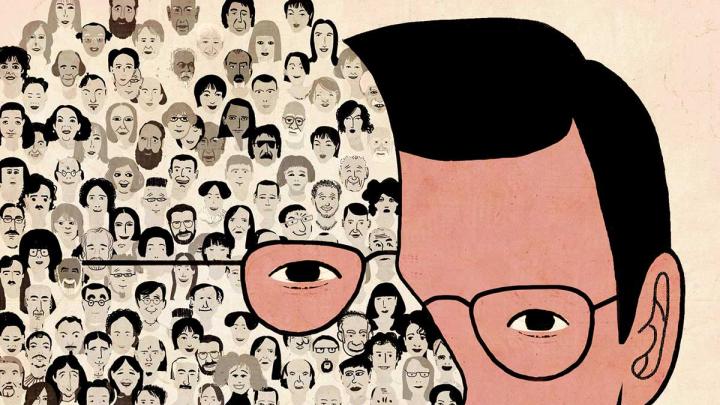

Few sites currently share that kind of history. Donath has been exploring ways to allow websites to represent users with “data portraits” that make it “possible to see years of activity in a single glance.” In The Social Machine, she writes, “Data portraits…can help members of a community keep track of who the other participants are, showing the roles they play and creating a concise representation of the things they have said and done.” She continues, “Communities flourish when their members have stable identities,” and the protection of a pseudonym may free users to debate controversial topics more fully.

In the early days of online communities in the 1980s and ’90s, idealistic writers praised these forums for untethering users from their physical bodies. They envisioned spaces where people could know each other not by their gender, age, or ethnicity, but by the words they wrote and the ideas they shared. “If you had a history of saying very smart, intelligent things, people would give a lot of credence to what you said,” Donath says. “If you had a history of being annoying, they would start to ignore you.” In the end, the reality was more complex: users became frustrated when people misrepresented themselves, and disposable e-mail accounts allowed people to generate spam or hate speech. In reaction, sites such as Facebook emerged to link Internet activity with a person’s real-world life and name. Advertisers welcomed this effort to consolidate all of a person’s information for marketing purposes.

Donath is hopeful that establishing conventions such as the use of pseudonyms will provide “this amazing opportunity to develop online spaces that are truly different from what we can make happen face-to-face.” (The Internet, she says, could provide new options for difficult negotiations, for example.) One of her goals is to help readers recognize possibilities between real names and online anonymity. She believes pseudonyms could provide more information, not less. “We can simultaneously have a rich impression of others and privacy,” Donath says. “They’re not [mutually] exclusive.