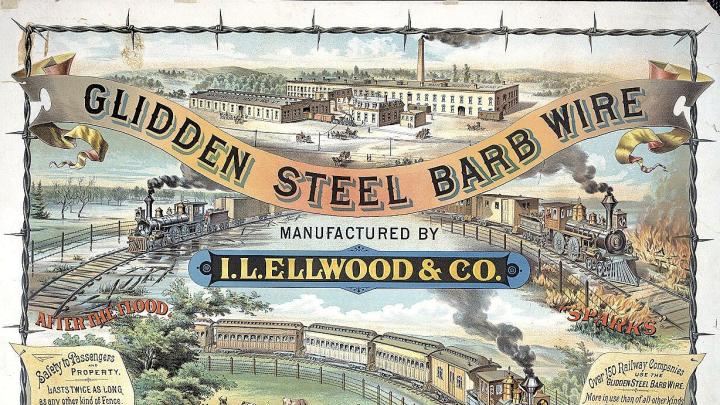

Has barbed wire ever been portrayed more glamorously than in the prettily framed advertising poster above for the I.L. Ellwood Company? A fence of the material, built to protect one’s livestock from oncoming trains, had clear advantages over a wooden fence. It would last twice as long. Sparks would not set it on fire. Floods would not sweep it away.

Railroads: The Transformation of Capitalism, an online exhibition created by the historical collections department of Harvard Business School’s Baker Library (see www.library.hbs.edu/hc/railroads/index.html), notes that the railroad industry required standardized, mass-produced parts for its daily operations, especially as the lines grew and merged with one another. By the late 1800s, the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia was producing nearly a thousand locomotives annually. Other companies manufactured thousands of specialized standard parts necessary for railroad operations, such as water injectors, signal oils, hydraulic pumps, ticket punches, and, indeed, barbed wire.

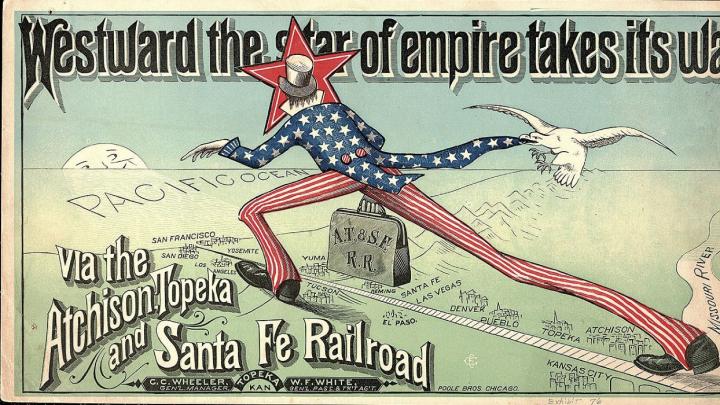

“Through the wide distribution of agricultural products, raw manufacturing materials, and finished consumer goods from other industries, the railroads fostered mass production and opened new national markets,” the editors of the exhibition text point out. “A company could create a mass-produced product—whether sewing machines or plows—in one region of the country and transport it via rail for sale in another region. The speed, efficiency, and scale with which items were produced and shipped resulted in lower costs.” The railroads set in motion the combined forces of mass production, distribution, and communication.

Productivity rose almost sixfold in the United States during the era of railroad expansion, as westward the star of empire took its way. The late Thomas K. McCraw, Straus professor of business history, wrote that during this period “the growth of big business was the central trend of the American economy.” The formation of what would become Fortune 500 companies spiked. By World War I, America’s journey from an agrarian society to a leading industrial power was complete. The editors of the exhibition sum up: “The rise of modern American capitalism, enabled by the expansion of the railroad, was one of the transformative developments of the nineteenth century—and one that historians refer to as the second industrial revolution.”