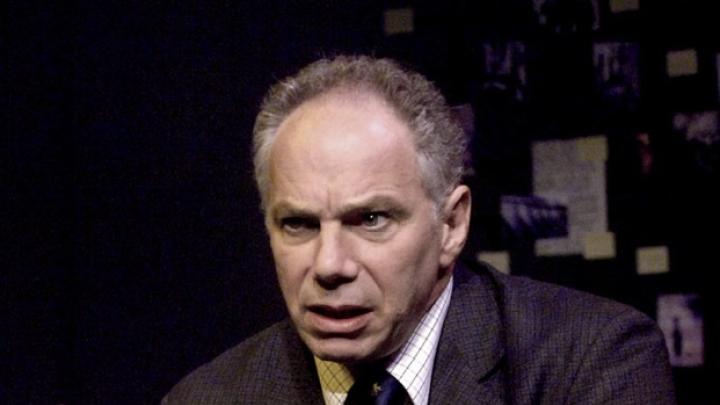

In 1990, Shakespeare & Company, the distinguished theatrical ensemble in Lenox, Massachusetts, had a problem: the departure of co-founder Kristin Linklater three months before the troupe’s winter acting workshop meant someone else would have to teach Shakespeare’s sonnets in her stead. Co-founder Tina Packer, RI ’95, asked actor Jonathan Epstein ’77 to step in. “At that point I probably knew about one and a half sonnets,” he recalls. “I tried to teach them the way Kristin had taught them to me. It was a total disaster. Since that was really unsuccessful, I got to thinking, over the next few years: what is important to me about the sonnets? By now, I’ve taught them to actors maybe as much as anybody—and so the act of teaching the sonnets is in itself a kind of artistic event.”

Indeed it is. Epstein (www.jonnyepstein.com) is a redoubtable Shakespearean actor whose voice infuses the poetry—today he knows about a third of the sonnets by heart—with clarity, thought, and feeling. “The sonnets are not intrinsically that funny, but they live on a kind of bed of wit,” he explains. “For an actor, they’re a training in nimbleness, [so you can be nimble,] even with a lot of depth—because in a sonnet you don’t get to stay in one condition for more than about a third of a line. They’re mercurial, with power behind them, because of the depth of the passion and the profound stakes: the risk is that one would not be loved.”

For years Epstein has brought his Shakespeare and sonnet workshops—which can last from half a day to a week—to theater companies, high schools, and colleges around the country. The participatory lecture-demonstrations combine a probqing investigation of the sonnets’ meanings with searching renditions by Epstein—and often by audience members as well. In the sonnets, he says, “there isn’t an attempt at obfuscation; I think Shakespeare’s doing his best to say how things are going for him. They’re authentic in a way that the plays aren’t; there’s no reason to suppose that Hamlet or Touchstone or Macbeth is speaking in his authentic voice. In the sonnets, that is his voice.”

Consequently, the sonnets are a way to “experience someone trying to speak as himself. Even if you’re the most articulate person who ever lived, you still fail oftener than you succeed.” He cites sonnets 109 through 112 as an example of how Shakespeare needed a sequence of poems to render the changing nuances of his feelings toward the “Fair Youth” who is the object of the first 126 sonnets. The poet used far different language for the mysterious, alluring Dark Lady of the remaining 28 sonnets.

“Shakespeare’s longing for the young man begins as an aesthetic appreciation, an admiration of youth, standing, power, being well connected—the things he himself didn’t have,” Epstein explains. “The sexual component is a third- or fourth-order item: see how cloaked the references are. With the woman, the sexual element is in the foreground from the start—it’s much more about coitus, possession, jealousy, and satisfaction.”

To explore the polarity between the sonnets’ Latinate words and those with Saxon roots, Epstein sometimes calls a student onstage to speak the contrasting lines antiphonally with him. “The Saxon is more rooted in the body,” he says, “the Romance words, in the lips and face and head.” Lines like “Or some fierce thing replete with too much rage/Whose strength’s abundance weakens his own heart” (sonnet 23) uses Latinate words (“replete,” “abundance”) for “plenty” and surrounds them with monosyllabic Saxon terms.

Regarding the young man, lines like sonnet 73’s “In me thou see’st the twilight of such day/As after sunset fadeth in the west,” Epstein explains, “have all these lovely sibilants—it’s fairly soft language. Then, when he’s talking about the woman (sonnet 129): ‘Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust,/Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight,/Past reason hunted, and no sooner had,/Past reason hated, as a swallow’d bait,/On purpose laid to make the taker mad….’ This uses the part of the body that’s lower; it uses the breath rather than the lips and the tongue. Hunted, had are more of a gasp from the lungs.”

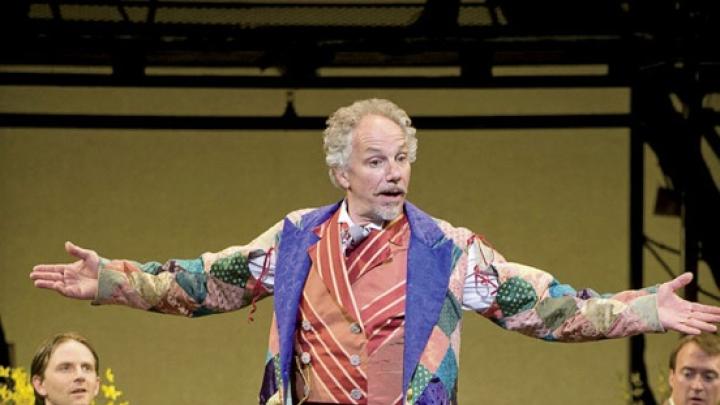

Such insights emerge from years of work as an actor, not from academic scholarship. Epstein first went on stage at eight; at Harvard he won the Boylston Prize for rhetoric and oratory and was advised by the late William Alfred, who had “an unbelievable capacity to admire. It was the kind of teaching you aspire to.” He began his long association with Shakespeare & Company in 1987, and to date has directed or appeared in more than 50 productions, including title roles in Macbeth, Richard III, and King Lear. (Shakespeare accounts for about half his stage work.) He’s also toured nationally in shows like Man of La Mancha and Dirty Dancing, and worked in regional theater, including many turns at Harvard’s American Repertory Theater. (Wryly, he notes that his 30-second role as Professor Zigman in last year’s Hollywood film Something Borrowed was seen by “more people than have ever seen me perform Shakespeare.”)

“For an actor, the sonnets are like a five-finger exercise for the soul, the way a pianist does scales,” he explains. “The body’s being exercised, but what is really being exercised is the mind’s connection with the body and the instrument and the material. For a pianist, the instrument is the fingers; for an actor, it’s the speaking and gesturing self. I’m creating a nimble, articulate channel for all those things to participate in the event together. The objective of the work on the sonnets is to create good Shakespeare players, so somebody can create depth and passion and wit when playing Portia, Orlando, or Dogberry.

“You don’t get to play Lear, or Shylock, or Rosalind unless you bring your whole self into the room,” he continues. “I used to think Shakespeare allowed us to be bigger than ourselves. Now I don’t. Shakespeare allows us to be life-sized, as big as we are. That’s enough. And anything less, isn’t.”