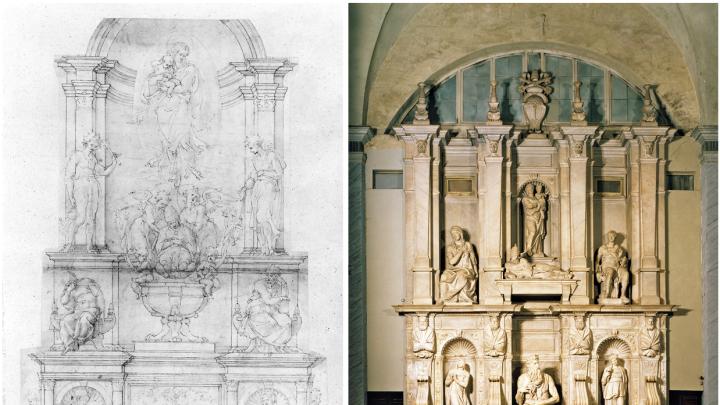

“The sketch on a cocktail napkin has become a modern-day shorthand for architectural epiphany,” writes Cammy Brothers ’91, Ph.D. ’99, an associate professor of architecture at the University of Virginia. The architect who interests her is best known as a painter and sculptor. In Michelangelo, Drawing, and the Invention of Architecture (Yale, $65), rather than examining his drawings for insight into his buildings, Brothers interprets his buildings (the Medici Chapel and Laurentian Library) as the product of his imagination worked out on paper. She dedicates the book to Howard Burns, an expert on Palladio who taught at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and to the late Adams University Professor John Shearman, a leading Michelangelo scholar. Brothers also benefited from time spent at the Villa I Tatti and Dumbarton Oaks.

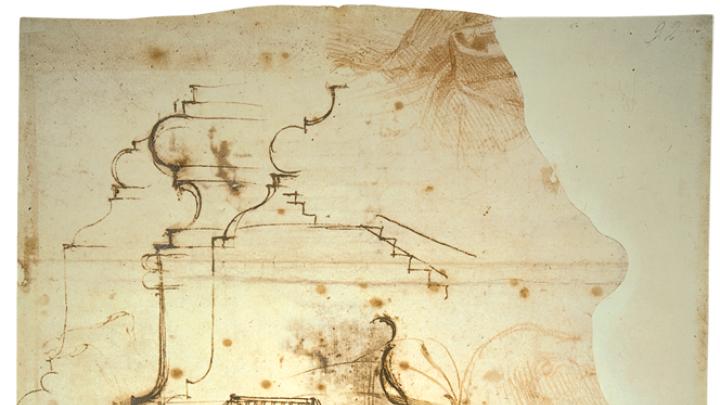

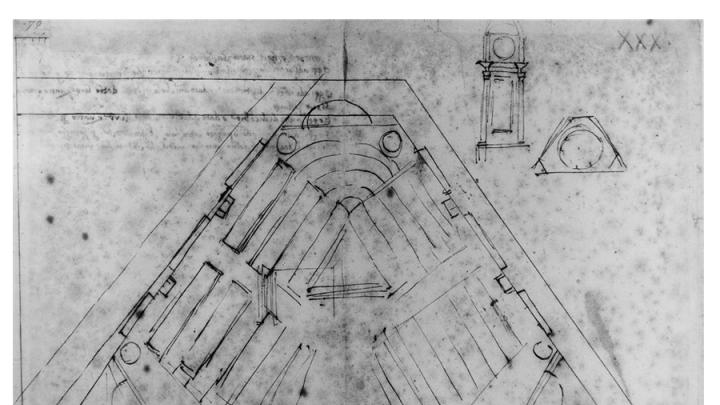

Michelangelo transformed the purpose and appearance of architectural drawings, and in so doing changed architecture itself. He demonstrated the possibility for architecture to be a vehicle for the imagination equal to painting or sculpture. The distinct character of his drawings… show[s] the way in which he would start with a remembered form, and how, in drawing and redrawing it, it would take on an entirely different aspect.…Michelangelo’s unusual approach to architectural drawing emerged from his figurative drawing practice.

The irony of Michelangelo’s architectural legacy, however, is that his fame eclipsed his influence. In other words, while he acquired renown for “breaking the bonds and chains” of architecture (in the words of Vasari), few were willing or able to follow his lead. The asymmetry between Michelangelo’s experimental and exploratory approach to architecture and drawing and its tepid legacy may in part be explained by the advent of architectural education.…As the [sixteenth] century progressed, so did an increasingly rigid set of expectations about what an architect should know—principally, a canonical set of Roman monuments and the details of the classical orders. Key to the formation of these standards was the use and diffusion of drawings and printed images of Roman monuments, which came to constitute textbooks of ancient architecture. The sheer repetition of a limited set of images narrowed the palette of representational choices and led to greater conformity.…

In general, surprisingly little attention has been paid by scholars to the connections between Michelangelo’s activities as a painter, sculptor, architect, and poet. These links would have been much more intuitively obvious in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries than they are today. In 1568, for example, Benvenuto Cellini stated that Michelangelo “was the greatest architect who ever was, only because he was the greatest sculptor and the greatest painter.” Yet much of the literature on Michelangelo has fallen prey to a sort of academic compartmentalization antithetical to the nature of his artistic production.