Student revolutionary, political refugee, gymnastics instructor, radical abolitionist clergyman: German-born Karl Follen was an unusual Harvard professor. He grew up during Napoleon's occupation of the German states; that conflict fired his generation's ideal of a united fatherland liberated from foreign domination and domestic fragmentation. At the University of Giessen, where he studied law, he became a leader of a radical fraternity for which he wrote political essays and poems. Their regimen of self-discipline included gymnastics and patriotic songsan agenda considered seditious by the authorities.

Follen's radicalism culminated in his support of fellow student Carl Ludwig Sand, who in 1819 murdered the Russophile diplomat and dramatist August von Kotzebue, who had publicly ridiculed the students' ideas. Follen destroyed letters that linked him to Sand, but his notorious commitment to violence in the name of freedom caused the historian Heinrich von Treitschke to label him "the German Robespierre." He escaped to Switzerland, but, fearing extradition, fled to New York in 1824. The Marquis de Lafayette aided him with introductions to prominent Americans.

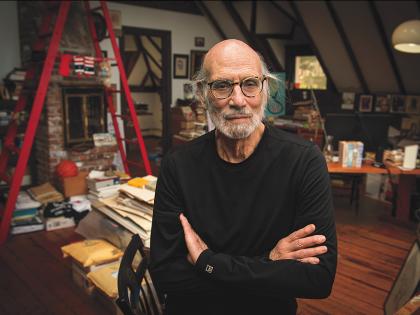

|

| The 1841 portrait engraving of Follen appeared as the frontispiece of Eliza Follen's edition of her husband's works. |

| Photomontage by Bartek Malysa. Portrait courtesy of the Harvard University Archives. Book from the collection of historical textbooks in the Special Collections, Monroe C. Gutman Library, Harvard Graduate School of Education. Gymnastics engravings from Turnbuch für die Söhne des Vaterlandes (1817), by J.C.F. Gutsmuth, courtesy of the Harvard College Library. |

The 28-year-old refugee anglicized his name to Charles and began a new career at the Round Hill School in Northampton, Massachusetts, brainchild of Göttingen-trained Harvard classmates George Bancroft and Joseph Cogswell. The curriculum, modeled on the classical German Gymnasium, included German and gymnastics. Meanwhile, works by Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Madame de Staël had sparked American curiosity about Goethe and German philosophy and theology. Soon Follen was offered a job by Harvard's young professor of modern languages, George Ticknor. German lessons had been available privately to Harvard students, but Follen's course was genuine pioneer work.

Andrew Peabody, A.B. 1826, described that first class: "There were no German books in the bookstore....The German Reader for Beginners, compiled by our teacher, was furnished to the class in single sheets as it was needed, and was printed in Roman type, there being no German type in easy reach. There could not have been a happier introduction to German literature...." The Reader and Follen's 1828 German Grammar launched the systematic teaching of German in the United States. Their enthusiastic and engaging author was also charged with setting up the first gymnastics program at the College; elaborate apparatus was constructed on the Delta, the triangular plot where Memorial Hall now stands.

For Boston's Germanophile Transcendentalists, Follen became a mediator of the exciting new world of German thought, someone who could discuss with Bronson Alcott, for example, the educational theories of Johann Pestalozzi. His systematic approach offered (to use Theodore Parker's words) a foil of "precise thinking" to the Transcendentalists' own "freethinking." Follen's social place was assured by his marriage to Eliza Lee Cabot. In 1830, her family funded his professorship, and the Follens built a house on the corner of the Cambridge street that now bears their name. The family's Christmas tree, charmingly described by the visiting English writer Harriet Martineau, gained Follen credit for introducing this German custom to the United States.

The mid 1830s were a tense period at Harvard. Because Follen opposed the strict disciplinary measures that President Josiah Quincy imposed on undergraduates, he and his wife were suspected of fomenting student unrest. Although Follen claimed he was dismissed in 1835 for his growing abolitionist views, Quincy's antipathy was probably an equal factor. (German continued to be taught at Harvard, but not until 1872 did the University create another professorship in the field.)

The Unitarian church gave direction to Follen's life after Harvard. The secular Lutheran was drawn to Boston's liberal Unitarian circles through his friendship with the movement's controversial local leader, another Harvardian, William Ellery Channing. Follen was ordained at Channing's urging, and took a pulpit in New York City in 1838, only to be dropped within the year after alienating the congregation with his extreme abolitionism.

Dejected by this loss, Follen thought of returning to Germany. In 1839, however, he was hired by a Lexington, Massachusetts, congregation. That winter he broke off a lecture tour in New York to return for the dedication of his new parish church. His steamboat sank in a storm, and Channing could not find one Boston church willing to hold a memorial service for a man who was marginalized socially and financially for his fierce abolitionist rhetoric.

In 1837 Follen remarked to his wife, "Had I been willing to lower my standard of right, the world would have been with me, and I might have obtained its favor." Instead he lived by the lines he sent to Harriet Martineau: "Those principles in which we live and move and have our being, though as old as the creation of man, are still a new doctrine, the elements of a new covenant, even in civilized, republican, Christian America. They are as the bread and wine of the altar, to which all are invited, but which few partake, because they dread to sign in their own hearts the pledge of truth which may have to be redeemed by martyrdom."

Thomas S. Hansen, Ph.D. '77, is professor of German at Wellesley College.