In the months following Hamas’s terrorist attack on Israel and Israel’s military response in Gaza, American Jews and Muslims have endured a rise in hatred. In the two months after October 7, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported a 337 percent increase in antisemitic incidents and the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) recorded 178 percent more complaints than the previous year.

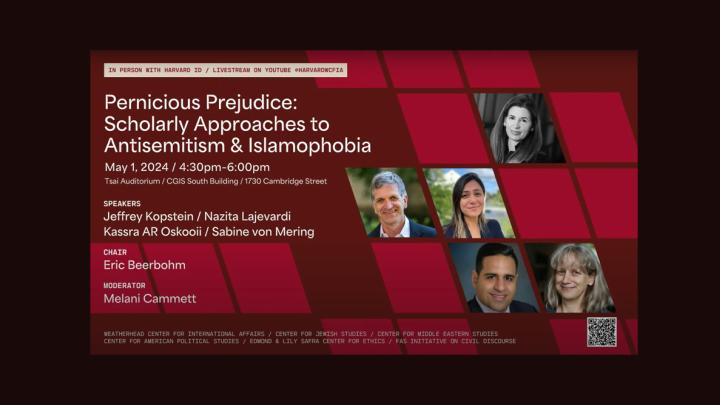

But antisemitism and Islamophobia are not new phenomena. On May 1, Harvard convened four scholars of antisemitism and Islamophobia whose research began long before October 7, and whose work can help unpack the recent rise in hatred. The panel, “Pernicious Prejudice: Scholarly Approaches to Antisemitism and Islamophobia,” was part of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ Civil Discourse Initiative, announced in December in response to Harvard’s tumultuous fall semester.

Testing Campus Sentiments

Unstable campuses were of great interest to University of California Irvine political scientist Jeffrey Kopstein. He wondered how many students harbor antisemitic and anti-Israel sentiments. Are those feelings changing throughout the course of college? He surveyed slightly more than 2,000 students from four University of California locations, asking whether students agreed or disagreed with six statements to gauge antisemitic opinions and six for anti-Israel opinions.

He found that there were indeed antisemitic sentiments on campus, but that their prevalence among students was about in line with the rest of society. Those hateful thoughts were spread evenly among freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors—their frequency did not increase or diminish. (Anti-Israel sentiments, on the other hand, do increase as students age.) “I think the implications of the findings,” Kopstein said, are that “the United States does not have a campus problem: it has an antisemitism problem.”

His team was about halfway through collecting data on October 7, leading to a natural secondary experiment. How did campus feelings toward Jews and Israel change after Hamas’s attack and Israel’s military campaign in Gaza? The survey results demonstrated an increase in antisemitism after October 7, though Kopstein said he is not sure whether people were more willing to vocalize existing prejudices or if they became “more convinced that Jews are doing bad things.” There was also a jump in negative feelings towards Israel, which Kopstein attributes to the country’s military response to the Hamas attack.

Reflecting on his data, Kopstein wants to pursue two follow-up studies. First, what would be revealed if he asked the same 12 statements on different campuses? The four UC schools he sampled all lean left politically and have more minority students than white students. He said he’d like to poll a campus that’s more conservative and more white to see if he gets a different result. Second, he wants to follow up on one of his polled statements concerning the antisemitic myth that Jews use Christian blood for ritual purposes. Though only 5.8 percent of students agreed that they do, he wants to study the surprisingly large percentage who marked “slightly disagree” rather than “strongly disagree.” Arguably, he said, “slightly disagree” is an antisemitic response, and that could be where more antisemitic sentiments “are hiding.”

Replaceable Hatred

Another panelist, Michigan State University political scientist Nazita Lajevardi, wants to figure out who is hating Muslims and Jews. Lajevardi has observed a rise in hatred against both groups in the last seven years, pointing to the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, as the moment where hateful far-right rhetoric resurfaced. She wondered whether there is a group of people who hate both Muslims and Jews—and are those types of hatred linked?

Lajevardi analyzed offline hate using information from the ADL, CAIR, and FBI, and online hate using databases of social media posts on Reddit, 4chan, and Gab (she described the last two as “fringe alt-right social networking sites”). Analyzing data from 2016 to 2019, she said she found that there is a group of people who say that both Muslims and Jews “contribute to all problems in American society.” These “extremists high in religious ethnocentrism” treat antisemitism and Islamophobia as “replaceable hatred,” she said, swapping one target for another. In the month prior to the Unite the Right Rally, Lajevardi said, online slurs against Muslims and Arabs began to drop, and immediately after the rally, slurs against Jews increased.

The idea that antisemitism and Islamophobia might be driven by the same group of people changes the conventional understanding of these forms of hatred. “Contemporary discourse…pits American Jews and Muslims at odds,” she said. But her research demonstrates that “a large amount of seemingly disconnected hateful rhetoric about these groups…was being advanced by the same far-right extremist communities.” She hopes that researchers and politicians will further investigate the source of these combined bigotries and analyze the impact of far-right communities.

Engaging with Hatred on Social Media

The ways that hatred spreads online fascinate Sabine von Mering, professor of German and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at Brandeis University. In 2022, she co-edited Antisemitism on Social Media, a book that she hopes will help scholars analyze antisemitism from a modern, computer science perspective, not just as historians. Too often, she said, people refer to “online” as a monolith. “Antisemitism and Islamophobia aren’t surging on websites,” she said. They are “spreading through algorithm-driven user-generated content, and it is highly profitable.”

She offered one concrete piece of advice to the audience: do not engage with hateful social media posts. “When you directly engage with online hate,” von Mering said, “you’re actually becoming part of the problem because the algorithm doesn’t care whether you engage with a post because you liked it...The engagement is what counts: it’s what advertisers pay for.” Instead, she recommended reporting the hate and screenshotting it.

But the reporting mechanisms on social media platforms are woefully inadequate, von Mering continued. She argued that there are not enough content moderators for moderation to be effective and that moderators focus too much on the United States, ignoring other parts of the world. “Spending millions on content moderation is a joke when you have billions of users,” she said.

The Distinct Case of Islamophobia

After much talk about hatred, University of Delaware political scientist Kassra AR Oskooi argued that scholars must not lose sight of the distinct aspects of Islamophobia. Saying that anti-Muslim sentiments are just part of a general ethnocentric hatred, he said, obscures “the distinct profiles of threat that are associated with different populations.”

Among those who express Islamophobic sentiments, Oskooi described two types of perceived threat—symbolic and safety. Symbolically, despite a general disposition toward religious tolerance, “There exists a prevailing perception among Americans that Muslims hold values that are particularly incompatible with their own.” To track symbolic threat levels, he measured support for cultural restrictions, like limiting the number of mosques Muslims could build in the United States.

In terms of safety, Oskooi said, Muslims are often associated with tropes of terrorism and violence. To measure this safety threat perception, he tracks support for policies that would scrutinize Muslim-American security, like banning Muslims from buying guns or requiring Muslims to undergo annual security checks. These specific prejudices towards Muslims, he argued, create "conditions under which it becomes easier to justify the indiscriminate surveillance of Muslims” and limit “their religious freedom and expression, which would otherwise be considered un-American.”

A Scholarly Perspective

To open the panel, Dillon professor of international affairs Melani Cammett said that the event was not “aimed at focusing on the conflict” or “how it is reverberating on campuses,” but instead would highlight “scholarly approaches to the core issues.” In a week where campuses continue to grow divided, disrupted both by protests and police responses to protests, the panel helped display how universities can weigh in on timely issues by sharing existing scholarship. To these professors, antisemitism and Islamophobia are more connected than they appear. Each has its unique aspects, but the similarities in who spreads hatred and how it is disseminated demand further investigation.

View the conversation below: