Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

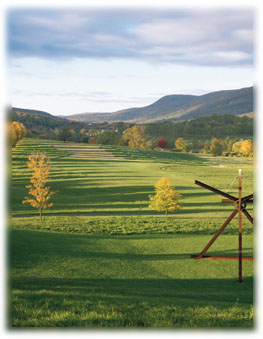

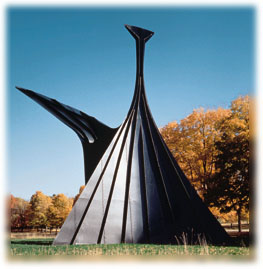

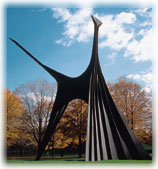

STORM KINGNature meets Technology. Peter Stern manages the introductions.by CHRISTOPHER REED    Mark di Suvero's Pyramidian, completed last September, is shown in its entirety at lower left. A suspended 60-foot horizontal I-beam moves almost imperceptibly in the wind. Lower right: Mother Peace, made by di Suvero in 1969-70. Mark di Suvero's Pyramidian, completed last September, is shown in its entirety at lower left. A suspended 60-foot horizontal I-beam moves almost imperceptibly in the wind. Lower right: Mother Peace, made by di Suvero in 1969-70. |

"Before I went off to Harvard," says H. Peter Stern '50, "my father asked me what I thought I might study and strongly suggested engineering as a preparation for business. Everybody in my family had been in business. As a snotty adolescent, I told him I wasn't sure what I wanted, but I knew I wouldn't go into business. I thought I might do something on the international scene, like at least become secretary of state."

Stern went into the hardware business. At 28 he had formed a close relationship with his then father-in-law, Ralph E. "Ted" Ogden, who ran the family-owned Star Expansion Company, which manufactured metal fasteners in rural Mountainville, New York, in the Hudson River valley. Ogden asked Stern to come into the business. He did, in 1956, became president two years later, and eventually bought Ogden out. "'I've made enough money,' Ted Ogden told me. 'Now I want to start spending it.'"

In 1958 Ogden, through a family foundation, bought a 180-acre estate in Mountainville on which his friend Vermont Hatch '13 had built a Normandy-style château on a plateau overlooking the valley between Schunnemunk and Storm King Mountains. The property became the core, later greatly augmented, of Storm King Art Center, founded by Ogden and Stern, with Stern as chairman and president. It opened in 1960.

The founders' vision at first was to exhibit work by painters of the Hudson River school. But Ogden began to acquire sculpture. Both he and Stern had deep love for the region's landscape. They decided to make the art center a sculpture garden, where they would explore the challenges of harmonizing the bucolic beauty of the landscape with the drama of the sculpture.

In 1967 Ogden went to Bolton Landing in upstate New York, the home of the sculptor David Smith, who had died two years before, and "without hesitation paid what seemed at that time a very large sum to acquire all at once 13 Smith sculptures for Storm King," says Stern. "He said he would make many mistakes in life buying sculpture, but would do at least one thing right." "Storm King has a very important collection of David Smith's work, and it is beautifully displayed," says Sarah Kianovsky, assistant curator of paintings and sculpture at the Harvard University Art Museums and an authority on the sculptor.

|

"It is an international collection with more than 100 artists represented," says Stern, "but it omits work by some excellent sculptors because their pieces would not fit into this landscape. A sculpture might demand too formal a setting, for instance. Acquisition decisions are made by a very good committee of the trustees, but I have a senior voice, and David Collens, the art center's longtime director, has got very good eyes."

Stern and Collens, often with the participation of the sculptors themselves, take the greatest care to site sculptures sensitively in relationship to the landscape. "Works of art should not be seen in isolation, they should be seen in a beautiful context," says Stern. "Every period of high civilization has shown great art in beautiful houses, beautiful gardens. That is why I have such a strong feeling about giving everything space, of putting sculptures in relationship to everything else. And of not overdoing things." Stern is on guard against overfilling the garden.

Mon Père, Mon Père, 1973-75, and down the greensward Pyramidian. A sculpture needs space, says the artist, "for the piece really to breathe, to reach its maximum transmission." Mon Père, Mon Père, 1973-75, and down the greensward Pyramidian. A sculpture needs space, says the artist, "for the piece really to breathe, to reach its maximum transmission." |

Visitors walking Storm King's rolling landscape may well imagine that the grounds are as the glaciers shaped them, but this is far from the case. When Ogden acquired the original property, the plateau on which the house sat dropped precipitously to the valley because an assault by bulldozers in the 1950s had taken two million cubic yards of gravel for the construction of a piece of the New York State Thruway. Landscape architect William Rutherford put equivalent yardage back and has since then made hills and valleys, planted shrubs and trees, carved vistas, and otherwise worked the land to make ideal settings for sculpture. He has created a naturalistic landscape garden that "Capability" Brown would have admired. Says Peter A. Bienstock '62, LL.B. '64, chairman of the art center's executive committee, "While Storm King contains great sculpture, perhaps the greatest sculpture of all is the brilliantly crafted landscape itself."

|

In 1985 Stern's company gave the art center the proximate side of Schunnemunk Mountain--2,100 acres of unspoiled woodland. Almost all other land visible from the place is protected, and the art center is working to achieve totality. Today, a visitor to Storm King may turn in any direction and see the sculpture garden against rolling hills that show no sign of the human hand. The landscape for sculpture now stretches for 500 acres. With its mown meadows, allées, pond, well-tended woods, and its great, specimen sculptures--embodiments of technology--it looks like the king's parkland in a fantastic realm.

"Business was never my primary interest," says Stern. Although he has yet to be Madeleine Albright, his life has been eventful. He was born in Hamburg, where his grandfather had started the largest oil company in Germany. Stern's father had followed into that business when Shell Oil bought the company and in 1928 sent him to Romania to manage Shell there. "In 1938, when the situation in Europe worsened," says Peter Stern, "I was sent away to St. Bedes' School in Sussex, England, and then to the École Internationale in Geneva, and then in 1940 we left Romania, a traumatic experience, and came to this country, to Scarsdale, New York."

Alexander Calder's sculptures with moving parts were christened "mobiles" by Marcel Duchamp. Jean Arp called the others "stabiles." Here are three views of The Arch, 1975, a stabile. Alexander Calder's sculptures with moving parts were christened "mobiles" by Marcel Duchamp. Jean Arp called the others "stabiles." Here are three views of The Arch, 1975, a stabile. |

Stern went to Yale Law School but, undecided, interrupted his studies to get a master's degree from Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs. His thesis was published as The Struggle for Poland. Then he went back to Yale to finish with the law.

He practiced law in Washington, D.C., married, and went to Mountainville to embrace metal fasteners. In deference to his youthful ambitions, he has long been a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Interests more useful cardiovascularly have included dressage riding, skiing, and tennis.

His first marriage ended after 20 years. A bachelor again, he took cooking lessons in New York City--Indian and Western. "I gave parties, but I quit because I learned what housewives are up against," says Stern. "The success of a party is good conversation, but every time I ran into the kitchen, I got left out of the conversation. I sat down at the table again, and my dinner partner to the left was looking this way, and the other one was looking that way, and I couldn't get back in."

Stern went to mime school in Manhattan for three years and did so well that he was invited to go on the road with a theater troupe. He would have had to abandon his business and the art center, and so declined the offer. When he later married the research biologist Margaret Johns, who was very busy establishing the relationship between mammalian physiology and the vomeronasal organ, but who nevertheless wanted to know what went on in his life, she would come back from her lab at night and get into bed (a remarkable, Indian, canopy affair, with the mattress platform suspended from the canopy by ornate brass chains), and he would act out for her whole board meetings.

She played the piano and encouraged Stern to revisit the violin, which he had tried as a boy, so that they could play together. "My teacher said, 'Sir, at your age (I was 52), you should take many lessons from me and you should not practice, you'll only get bad habits.' So I've taken a lot of lessons, and now I play chamber music." Of his quartet, he says, "I wouldn't advise anybody to make a long-distance trip to hear us, but it's fun.

| FOR THE VISITOR The Storm King Art Center is in Mountainville, New York, close by the Hudson River, 55 miles north of Manhattan and 7 miles south of Newburgh. Telephone (914) 534-3115 for directions. The art center is open daily from 11 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. from April 1 through November 15. Admission is $7, $5 for senior citizens, $3 for students, and is free for children under five. The main building offers galleries and a museum shop. June through August the grounds are also open on Saturdays, and Sundays of holiday weekends, until 8 p.m., with admission free after 5. One may picnic, but not cook, in designated areas. For groups of 10 or more, free docent-guided tours are available; reservations are required. |

"I had a seventieth-birthday party recently and my son, knowing the answer, asked me to name the most important things in my life. I said, 'Wine comes first, then you children and my wife come next. [Stern was once a member of the Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin, a merry band.] Music is my deepest interest and love in life, classical music first, but Indian music as well. Music is tied with wine.'" Stern also collects Persian miniature paintings and Asian textiles, which cover the walls of his home in Mountainville, and he is a member of the Hajji Baba Club, a merry band of rug fanciers.

More earnestly, Stern has since 1972 been vice chairman of the International Fund for Monuments. The Italian government awarded him the Order of Merit for personally making possible the restoration of the organ and other parts of the Church of Santa Maria del Giglio in Venice. He has campaigned for the conservation of Angkor in Cambodia, recruited his friend Thor Heyerdahl for help on Easter Island, and was the first contributor to the effort to restore Constantin Brancusi's Endless Column in Targu-Jiu, Romania. All this has required much travel to distant places, which has accorded well with Stern's resolve, after reading Arnold Toynbee's autobiography, to follow the historian's lead and see all the great historical and architectural sites of the world. This, Stern believes, he has mostly accomplished.

What has he accomplished on the ground in Mountainville?

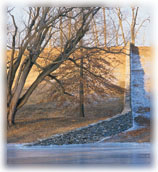

Andy Goldsworthy's six-foot-high Wall That Went for a Walk meanders for 2,278 feet, embraces trees, descends a hill, plunges into a pond, climbs out on the other side, and runs to the New York State Thruway. It was made by Scottish wall-builders in the cool seasons of 1997 and 1998. Andy Goldsworthy's six-foot-high Wall That Went for a Walk meanders for 2,278 feet, embraces trees, descends a hill, plunges into a pond, climbs out on the other side, and runs to the New York State Thruway. It was made by Scottish wall-builders in the cool seasons of 1997 and 1998. |

J. Carter Brown '56, M.B.A. '58, director emeritus of the National Gallery of Art and a trustee of the art center, answers the question thus: "There is no question that among sculpture parks of the world, Storm King is king."

"People ask how Ted Ogden and I came up with the vision for the art center. But it wasn't a matter only of vision, it was also about opportunity," says Stern. "The land was cheap. Big sculptures were just beginning to be built, and they were affordable. Engineers were available in my company to help with installation and conservation. If I'd indulged some of my other interests--seventeenth-century Dutch painting or French eighteenth-century furniture--I could have acquired one object. But Storm King was something that could be done. I was here at the right time."

"Storm King is very well regarded both in terms of the quality of the sculpture and its siting," says Linda Norden, Lee associate curator of contemporary art at the University Art Museums. "Its pastoral landscape is gorgeous and is ideal for a certain type of work, for David Smith's, for example, and other modernist sculpture. Mark di Suvero's several pieces at Storm King look wonderful there, but they lose some of their grit. Sculpture made out of the city's detritus is best seen in the city. The pastoral setting is less suited for much of today's work, which aims at a cultural critique. In the art world, Storm King is seen as uplifting, gorgeous, but dated."

Di Suvero, on the other hand, exults about this venue for his work in Sculptors at Storm King: Seven Modern Masters Reveal Their Creative Adventures, a video made by the center. "The idea of taking what human beings do and putting it in nature--we are part of nature--is a brilliant idea," he says, pointing out that a sculpture needs space "for the piece really to breathe, to reach its maximum transmission."

"Cohabiting at Storm King are two of the most potent myths of the American imagination: the machine and the natural paradise," writes critic John Beardsley '74, a senior lecturer in landscape architecture at Harvard's Graduate School of Design, in A Landscape for Modern Sculpture: Storm King Art Center (Abbeville Press, second edition, 1996). "No sculpture in the Storm King collection resembles a machine; indeed, many have a lyrical, anecdotal, or even erotic significance, not to mention a formal character, that runs counter to any kind of machine--or space-age look. But many ...are composed of the products of the factory and assembled by the most sophisticated techniques....Just as their forms can be seen to echo the natural surroundings, so do they aspire to evoke the same kind of exalted emotion we associate with the majestic setting. They do this through their scale, to be sure, but also through their reference to a myth of technology every bit as powerful and pervasive as that of the landscape. These myths are not synonymous; they do not converge: they are compatible instead in their magnitude and their hold on our imaginations. Storm King commits them to a respectful truce."

Sculptor Isamu Noguchi might agree that some of Storm King's inhabitants jar the eye. "I'm afraid that a lot of sculptures will be considered like a kind of pollution, like tin cans are, because they really don't belong, whereas rocks belong," he says in the video he shares with di Suvero. He wishes to work in a way that is "compatible with the landscape." Indisputably, surely, one piece of Storm King sculpture is well married to its surroundings. It is a 40-ton grouping of stones called Momo Taro, quarried, split, shaped, and polished in Japan by Noguchi specifically to sit on one of Stern's hills, reshaped to the artist's specifications. This is, says Stern, perhaps his favorite piece of sculpture at Storm King and Noguchi the living sculptor he most admires.

Left: Visitors to the art center confront Louise Nevelson's City on the High Mountain, 1983, as they leave the main building, which houses nine galleries. Right: Free Ride Home, by Kenneth Snelson, 1974. Left: Visitors to the art center confront Louise Nevelson's City on the High Mountain, 1983, as they leave the main building, which houses nine galleries. Right: Free Ride Home, by Kenneth Snelson, 1974. |

"Noguchi says that there are two ways of proceeding as a sculptor," says Stern. "One is to plan what you're going to do and then do it. The other is to create, and then see what you have done. Noguchi puts himself in the second category as an artist, and I'd say that's the way we have created the art center and I have lived my life."