Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

|

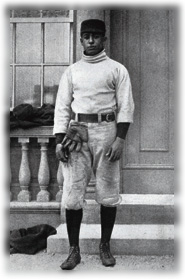

Last year Americans celebrated Jackie Robinson on the fiftieth anniversary of his breakthrough in major-league baseball. Robinson himself always honored those black ballplayers who faced the bitter constraints of segregation before him. One of them was William Clarence Matthews '05, who challenged the color line more than 40 years before Robinson.

Born in Selma, Alabama, and trained at Tuskegee Institute from 1893 to 1897, Matthews was a promising student and outstanding athlete who was sent north for further education, first to Phillips Andover and then to Harvard. From 1901 to 1905, he played shortstop on perhaps the best college team in the country (75 wins, 18 losses in his four years) at a time when baseball enjoyed singular appeal in the United States. It was not uncommon for players to walk off a college campus onto a major-league diamond: Christy Matthewson left Bucknell for John McGraw's Giants, and two of Matthews's teammates, Walter Clarkson and "Harvard Eddie" Grant, went on to play in the big leagues.

Matthews was a remarkable player--and his baseball career at Harvard was extraordinary. Compact and lithe at 5 feet, 8 inches, he could hit for both average and power, and was a dervish on defense and on the basepaths. In his first year, he was one of 140 candidates for the 12 spots on the team; the Crimson reported, "Harvard has quite a find in Matthews....He weighs only 144 pounds, but he more than makes up for that by his wonderful quickness, pertinacity, and sand." He scored the winning run in the Yale game that year before 9,000 fans, and for the next three years was Harvard's leading player. His senior-year performance included a .400 batting average and 22 stolen bases in 25 games.

During all four years, the Harvard team faced boycotts and tension on and off the field. In his first season, Matthews was held out of games against Navy and Virginia; in his second year, the team called off its annual southern trip altogether. His own behavior remained impeccable. McClure's Magazine held him up nationally as "the best there is in a college athlete"--who "to maintain his amateur standing has repeatedly refused offers of $40 a week and board to play semi-pro baseball in the summer." (All the while, he had been earning his way at Harvard, taking jobs during the school year, working summers in Pullman cars and hotels, and teaching in a Cambridge night school.)

Matthews played his only season of professional baseball in the summer of 1905, in Vermont's "outlaw" Northern League. Again he encountered players' boycotts and verbal and physical abuse. On July 15, while he was playing for Burlington, the Boston Traveler speculated that he would cross the "line" and play for a major-league nine. Fred Tenney, player-manager of Boston's National League team, only a half-game from last place, was keen to add Matthews to his roster. The story attracted national attention. The Traveler also printed Matthews's statement on the matter.

I think it is an outrage that colored men are discriminated against in the big leagues. What a shame it is that black men are barred forever from participating in the national game. I should think that Americans should rise up in revolt against such a condition.

As a Harvard man, I shall devote my life to bettering the condition of the black man, and especially to secure his admittance into organized baseball.

If the magnates forget their prejudices and let me into the big leagues, I will show them that a colored boy can play better than lots of white men and he will be orderly on the field.

But the "magnates" would not allow it. And at the end of the summer, Matthews returned to Boston and got on with his life.

Unlike many other black players, he had options off the diamond. He had taken courses at Harvard Law School as a senior; now he earned an LL.B. at Boston University while working as an athletic instructor at Boston high schools. He passed the bar in 1908 and embarked on a legal and political career; in 1913, with the help of Booker T. Washington, he was appointed special assistant to the U.S. district attorney in Boston. From 1920 to 1923, he served as legal counsel to the black separatist Marcus Garvey.

Even while working with Garvey, he remained involved in Republican politics, and he played a major role in the 1924 presidential campaign. When Calvin Coolidge was elected with the help of a million black votes, Matthews was rewarded with a post in the Justice Department--but a list of "demands" for the "recognition of colored Republicans" that he presented to party leaders was ignored. Whatever else he might have accomplished was thwarted when he died of a perforated ulcer at 51. His death was reported in all the major East Coast newspapers: the Boston Globe called him "one of the most prominent Negro members of the bar in America." The black press ran front-page headlines.

Matthews said in 1905, "A Negro is just as good as a white man and has just as much right to play ball." On the diamond, at Harvard and elsewhere, baseball offered him a glimpse, however fleeting, of the ideal of equality. In his baseball career, and after, Matthews asserted his right to "play ball" in America.