Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

|

|

I came to Harvard College with a clear sense of who I was and a core-of-my-exis-tence determination no one should ever find out. For four years, not a soul did. But as I recently told 600 ninth- through twelfth-graders when I was in-vited to my high school's second (no less) annual gay and lesbian awareness assem-bly: When I was sitting where they were sitting, there wasn't an hour that went by--not in six years at Horace Mann or the four that followed at Harvard--that I did not think of my one central

mission: namely, never to have anyone find out the horrific truth.

And there I was telling virtually the entire school.

...and as a Harvard senior. ...and as a Harvard senior. |

A couple of months later, they made me a trustee. Has this world ever changed.

One way of looking at all this is...uncomfortably. After all, most of us grew up knowing homosexuality was simply too shameful to discuss. Murder and mayhem can be regularly televised, but two men or women holding hands? Decency has its limits.

The better way of looking at it may just be to laugh at God's little joke--wiring 5 or 10 percent of his children differently from the rest. My own feeling, not being religious, is simply to concede what our born-again friends argue: that intimate relations between two people of the same sex are unnatural and perhaps even an abomination before God--if they're straight. If they're gay, it's the most natural thing in the world.

It took me the better part of 30 years to come to this easy, relaxed view. It has taken Harvard--and surely not all her children yet agree--far longer.

Condemnation of homosexuality goes back as far at Harvard as anywhere else in this country. The Reverend Michael Wigglesworth, A.B. 1651, author of the Puritan bestseller Day of Doom, certainly condemned it. He attended Harvard in its earliest years and was once even in the running for her presidency. Yet he lusted after his students. "Lord I am vile," he confided to his diary (portions of it written in code) in 1653.

There was little discussion of any of this back then, let alone debate over the existence of a gay gene. It was, rather, as Wigglesworth records his doctor's explanation, a condition caused by "a little acrimony" gathering in the mouth, which caused "humours to flow." Marriage, he was advised, "would take away the cause of that distemper." And so Wigglesworth married his cousin Mary "and consummated it...by the will of God May 18, 1655." But the news was not good. The very next day he felt "stirrings, and strongly, of my former distemper even after the use of marriage." And this made him "exceeding afraid."

From the age of 10, I was more than a little afraid myself. Through some tragic error--that seemed to have happened only to me--I was defective. I certainly wasn't a homo. I just felt a tremendous attraction to boys my own age and none at all--I mean none--to girls of any age.

I wasn't stupid, so I never told anyone about this. But it was the very essence of who I was. There wasn't a moment I wasn't consciously compensating for it. It was very much (I imagine) as if I had been a secret agent in a foreign country. Everything I said, every glance (I never looked longingly at what I longed for)...it all had to pass through the censor.

As junior year in high school rolled around, I began thinking about college. Not because I had any real notion of what that meant, besides finally having to go out into the real world (sort of). For this, I was utterly unprepared. For one thing, I couldn't do the twist. Dancing with girls was something that made me so nervous and self-conscious, I lost what little sense of rhythm and agility I otherwise possessed--which made me all the more nervous that it would be obvious something was wrong with me, which made me all the more inept. When it came to guy talk and nudging my buddies to check out the hot stuff coming up the street, I lived in constant terror. I didn't know which the hot stuff was. At any moment I was in danger of saying something so unbelievably inappropriate as to blow my cover.

I had no idea what I would do with my life--or how I could even have a life. Everyone normal dated and fell in love and got married and had kids, and that was what I would have to do--but it was, I knew, completely impossible. My sex drive, as I came to think of it, had been multiplied by minus one--the equation was the same, but all the signs had been reversed. And, as best I could tell, I was the only one. Again, I was not stupid (well, not completely stupid). I knew what a homosexual was: I had seen pictures--the pale, skinny person with long blond hair lying on the beach furtively, behind a boulder, beside the dark, bronzed, body builder. But this was not me.

I took periodic melodramatic walks, talking with myself about suicide, though never, I think, really seriously considering it. There was no need for that yet--any given day I could negotiate quite well. Horace Mann was then still an all-boys day school, and on weekends our family went up to a fairly remote country place where, for all my friends knew or cared, I was dating nonstop. My parents could see I didn't want to talk about my social life, and also that I had a date every now and then--a necessary torture. They must have just figured I was a late bloomer and, like a lot of teenagers, jealous of my privacy. Who had time for girls, anyway? I was competing to get into college.

My folks made it simple for me. They said I would go to Harvard. And Harvard, bless its heart, said OK.

To say that I am grateful and proud to be part of the Harvard family would be the grossest understatement. But while I was there, though I loved almost every minute of it, I was consumed with my ultimately unsolvable problem. Whether it was running Harvard Student Agencies or sitting in a Slavic literature class, my secret was as uppermost in my mind as sex is in any young man's mind. Perhaps you saw Europa Europa. It is based on the true story of a young Jewish boy who was sent from home to escape the Nazis but wound up at a school for promising Hitler Youth, his very survival dependent on never letting anyone know his true identity. Imagine how terrified he must have been even of taking a shower. Everything he heard and said had to pass in and out of his brain through a filter, multiplied by minus one.

Nat Butler, at home in Boston. Photograph by Marnie Crawford Samuelson Nat Butler, at home in Boston. Photograph by Marnie Crawford Samuelson |

I didn't know any gay men at Harvard--or didn't think I did. I later learned that my Winthrop House classmate Nat Butler '68, M.B.A. '75--whose heart was beating no more than 30 feet from mine for three years--was going through much the same thing I was, thinking he was the only one in the world (and surely the only one on the second floor of E-entry) who had this terrible secret. And I learned that two of Winthrop's best-liked tutors, Barney Frank '61, J.D. '77, and John Newmeyer, Ph.D. '70, were gay. And that my freshman proctor had been gay--indeed, that there had been gay parties going on in the basement of Pennypacker even as I was agonizing two floors up.

To all this, I was clueless.

More than that, I was a severe homophobe. The one housemate I did wonder about I treated with contempt, as almost any red-blooded American boy did back then--and there was nothing I wanted more than to be a red-blooded American boy.

Yet how could I square that with the fact that secretly I was completely in love with two of my roommates? (One went on to be mayor of Cincinnati, the other dean of students at a large university. We remain warm friends, my eventual revelation notwithstanding.)

On one level, I knew there probably were other people like me--regular guys who liked guys--much as we know, mathematically, there is probably other intelligent life in the universe. But how do you make contact? They would be hiding as determinedly as I was. Guess wrong, and you're finished. (It was actually Nat Butler's roommate I suspected--incorrectly.) I spent hours thinking of ridiculous schemes--anonymous random Soc Rel surveys I would send out, with replies to a P.O. box. Except that my survey wouldn't be sent out randomly at all, but to a select few. And it wouldn't be anonymous, either. The reply envelopes would be coded with imperceptible markings. And if one of them...if only...if...

Only once did I think of actually talking to anyone for advice. I was still a freshman, and I went to the office of Rustam Z. Kothavala, Ph.D. '64, the highly popular instructor of Nat Sci 10--"Rocks for Jocks"--and the freshman proctor who lived in the basement of Pennypacker with his wife and baby daughter. There was something simpatico about him I felt I could trust, and I was so depressed, so lonely and despairing, I went to his office, sat down, and began to talk. I was 17, he was 30.

I can't remember what I talked about, except that it was probably not geology, and it was definitely not "my secret." I came that close, but had trained myself too well. This was one secret agent they'd never catch.

"Oh, I remember it well," Rusty told me when I called 30 years later. We hadn't spoken in decades, though by now I knew he, too, was gay. "You hemmed and hawed for about half an hour--it dawned on me that maybe this was what was bugging you, but I felt it would be wrong to pry unless you brought it up first."

"But--but--," I sputtered, with questions about his wife and, well, everything else.

"The sixties were terrific fun," Rusty explained, cheerily. "I was at Harvard getting my Ph.D. and I remember I found a place in Boston opposite the bus station, a gay bar called the Punch Bowl, a big place with flashing lights. I was sort of wide-eyed and hesitant, and when I got to the door, the bouncer looked at me and said, 'Yeah, this is the place.'"

He had discovered the Punch Bowl through good old-fashioned legwork: "I spent a week going to downtown bars every evening until I found a gay one." Once there, he ran into "all sorts of undergraduates, grad students, proctors, faculty--it was a widespread network. Scores and scores of people." How big were the parties at Pennypacker? "Maybe 30 people, something like that."

And upstairs I slept.

Rusty had married in 1963, the year before I arrived at Pennypacker. In fact it was his wife-to-be who helped him come to terms with himself. He had been contorted and conflicted and finally told her. "Good lord," he recalls her asking, "is that all? Here I thought you were one of these international criminals or something."

And gay parties in the Pennypacker basement? Later, as senior tutor in Lowell House? Wasn't he afraid of being caught? "I believed it was perfectly all right to be gay. And I figured if people weren't tuned in, they wouldn't see it, so there was nothing to be concerned about. But I was also clear that I was not going to become sexually involved with any of the students, so that was easy. Following those simple rules, it was really all quite a breeze."

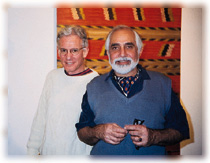

Toby Marotta (left) and Rusty Kothavala, at home in Tucson. Photograph by Simon Donovan Toby Marotta (left) and Rusty Kothavala, at home in Tucson. Photograph by Simon Donovan |

Rusty, now 64, is the patriarch of a growing clan of younger relatives in India, where he resides for several months each year. "I'm 'Granpa' and very openly gay, at that, to a flock of school-age Indian youngsters," he says. In the United States, he manages assets in Arizona and Hawaii amassed at least in part from his days as a dealer in museum-quality mineral specimens. He lives in Tucson with his life-mate, Toby Marotta '67, with whom he became acquainted 32 years ago in Lowell House. Marotta is the author of the 1982 book Sons of Harvard: Gay Men from the Class of 1967 (all but one of whom insisted on anonymity). "The first person to open my eyes in a way that made me more accepting of my homosexuality was Rusty," Toby explains in that book. "He was so at ease with his homosexuality and so judicious in the ways he expressed it that I didn't even know what his sexual preferences were until after we had become fast friends. Rusty was the first person to show me that someone could be gay and yet also professionally successful, popular, idealistic, shrewd, and adventurous."

"You'll be speaking with Toby?" Rusty asked when I reached him in Bangalore. "Please tell him I'll be getting back Tuesday."

It was all so natural and easy. But this was now. Thirty years earlier such ease--at least for me--was unthinkable. For me, each football game, each mixer, was a time of enormous self-conscious anxiety. Many other gay Harvard undergraduates were at least vaguely interested in girls and able to put up a front without too much angst. And some were not quite so naive as I was, or quite so intent on being the red-blooded American boy. Most of those guys were in Adams House. (Or so at least I have later come to surmise.) And most of them had probably read Oscar Wilde and had had experiences with an older boy down the block--whatever.

But not me. And, I expect, not my friend Bill. Harvard men like Bill and me were not casual about our sexual orientation--or confused. We knew what we were; we knew it was completely unacceptable; and we knew there was no way out.

Or so I suspect about Bill, anyway. I never talked with him about any of this. No one did. But a few years later, after he had finished Harvard College and Harvard Medical School, in the top ranks of his class, and was beginning his residency, he put a shotgun in his mouth and blew his brains out. I was completely at a loss. How could anyone have done that, let alone someone so extraordinarily successful, handsome, and popular? My straight friends--his roommates, who knew him better than I had--came to the conclusion he did it because he was gay and couldn't deal with it. It wasn't that he seemed gay. He ran track, and was a strong, manly guy, albeit shy with women and something of a loner. And not from Greenwich Village or someplace similar, either--but from a small town in Pennsylvania. But this is what his roommates, who knew him best, decided must have been the case. Over the years, I've come to the conclusion they were probably right.

Even today, about a third of teenage suicides are thought to be gay kids unable to live in a world they feel despises them.

For some it was easier. At least a little. John Newmeyer was a tutor in his mid twenties at the time (with long hair and a famous, sexy, movie-star sister, Julie Newmar, all of which made me nervous). Today he is a vintner in Northern California with two young children whom he has fathered, and is raising, with their lesbian mother.

"I lived in Winthrop House from 1966 to 1969," he recalls. "In those days only Tom Hopkins '69"--the guy I was homophobic toward--"was flamboyantly 'out.' He was a magnet for a dozen embryonic gay Winthrop men. Our homoerotic world was very like the Oxford of Brideshead Revisited, with Tom as Anthony Blanche constantly egging us on. I was a cautious Charles Ryder; my Sebastian Flyte was Nick Gagarin '70--beautiful, aristocratic, charming, and responsive. It was a time of intense romantic friendships, resonant with youthful laughter and daring and rebellion. These friendships reached sexual consummation only rarely and hesitantly--for me, just four or five times. Late-night knocks on my door, awkward passionate embraces, long intense confessions..."

The transition from 1966 (when Newmeyer got to Winthrop House and the Ivy League was still pretty much a tweedy, traditional place) to 1969 (the year of the Strike, when he left) was extraordinary. Vietnam was the catalyst, but everything changed.

"The year 1969 marked the end of an era in sexual politics at Harvard," says Newmeyer. "Dress codes, parietal rules, same-sex Houses were on the way out. The civil-rights movement, the antiwar movement, the exploration of marijuana, the Strike--for us wannabe gays it all culminated in Stonewall. That was all we needed: we leapt out of the closet, became gay activists, and hesitated no longer about our sexuality. Actually, we pretty much concluded that it was a damn lucky thing to be gay in that blissful dawn."

Not for me. Not quite yet. And not for Nick Gagarin, ever. He committed suicide in 1971.

A year and some after graduating, I did manage to come out to one of my closest straight friends, and then to another and another and another. I still had not had sex with anyone, man or woman, as I went around, aged 22, spilling the beans.

If you think I bring shame on the Harvard name for having been so incredibly retarded, well, I tend to agree. The details became a book 25 years ago, under a pen name but still in print [The Best Little Boy in the World, by John Reid]. Suffice it to say that today I am happy and productive. My partner, designer Charles Nolan, and I have been to the White House a few times and when they ask how we'd like to be introduced, we are at ease asking them to have the Marine announce us as a couple, just like the others.

But any such thing was inconceivable to me while at Harvard--and to a lot of others as well.

"I thought it was pretty awful being gay at Harvard," says a classmate I'll call Bob. "After a suicide attempt sophomore year, I was assigned a nationally known Harvard guy as my personal psychiatrist. He wasn't comfortable with the topic or issue or subject or me, so he kind of said, 'So why don't you try this?' and sent me up to group therapy with the Biebers clinic at the Mass. Mental Health Institute. Aversive shock therapy. They showed us sexy slides. Slides of men gave you a shock, slides of women didn't. Comic in retrospect, but pretty awful at the time."

Only one person Bob knows of ever came out of this therapy straight (or at least determined to be straight). Ironically, others who'd never had any gay experiences--only feelings--met people and "learned the ropes" by being there. So the clinic may actually have helped some people in a completely unintended way.

Bob didn't need to learn the ropes, he needed to know it was all right to be who he was. "I had been quite active in high school, and I knew older people. Back when the vice squad would bust the bars. At Harvard I didn't have much contact except briefly with a professor who was quite well known. Every once in a while I'd go into town to Sporters"--the youthful, preppy gay bar for all of Boston and Cambridge for many years--"but I had this feeling there were almost no gay undergraduates. I went to a couple of parties, but nothing clicked. I took an overdose the day after one of those parties--maybe the usual sophomore slump--and then junior year I went out on that bridge that Quentin Compson in The Sound and the Fury jumped off, but I never jumped. I only remember heading for the bridge with pills in me, a romantic lit major. Next I knew, I woke up at Peter Bent Brigham with a catheter."

Bob's tutor was gay, and the one after that, but he talked with them about it only after Harvard. "It was all so secretive--such a taboo--truly the love that dare not speak its name."

And the proctors. Rusty was not alone. "Oh, the proctors!" Bob laughs. "So many proctors were gay, and many people 'knew' it, but it was unspoken. You wished you could talk to them, but you couldn't. As long as it wasn't spoken, it was fine--these guys were very popular. They loved their boys. Never touched them. Kind of like priests. Don't ask, don't tell."

Bob's cover, for a while anyway, was "dating a woman from Sarah Lawrence," he says. He had known her from high school. "She was after me! But she wound up being gay, too," he says. "I remember going down to New York, Thanksgiving weekend freshman year, and we were making out at the St. Regis--she had all her clothes off and I still had my tie on and said, 'Time to leave.' She got married to a Harvard man and divorced him and then became a well-known divorce lawyer and then started living with [a famous woman]."

Suicide attempts notwithstanding, Bob graduated magna and Phi Beta Kappa, then worked his way through graduate school writing "spanking pamphlets"--pornography--and avoided the draft for being gay and underweight. Today he's neither the happiest guy in the world nor the unhappiest, has produced his fair share of nonpornographic intellectual property, paid his fair share of taxes, and retains many of his straight Harvard friends. "My Harvard years were the worst period of my life being gay, but it's not like I hated Harvard," he says. "I didn't. I made great friends there."