Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

For more alumni web resources, check out Harvard Gateways, the Harvard Alumni Association's website

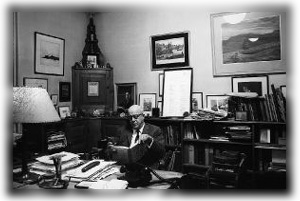

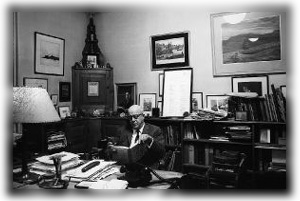

As executive director of the Harvard College Fund, in his office at #4 Wadsworth House, in 1963.Harvard News Office As executive director of the Harvard College Fund, in his office at #4 Wadsworth House, in 1963.Harvard News Office |

|

alumni.mccord "Few men have ever made and held so many friends for this University," David McCord once wrote of a departed colleague. No one can have brought about more such friendships than McCord himself. In his several capacities as fundraiser, editor, historian, and bard, he carried on a lively, literate, and long-running dialogue with thousands of his fellow alumni. Inevitably, irresistably, his Harvard--the Fair Harvard he had known and loved since his freshman days in 1917--became their Harvard.

McCord was in his hundredth year when he died on April 13. Much of his long life was devoted to Harvard affairs. For almost four decades, as the Harvard College Fund's executive director, he set new standards for American college and university fundraisers; for six and a half years he also edited the Harvard Alumni Bulletin. At the same time he produced a steady flow of poems and essays, mostly written in the hours after midnight, and was a skilled watercolorist who had 10 one-man shows from the early 1940s through the mid 1960s.

Retiring in 1963, McCord remained a prodigy of creative energy. Over the next 15 years he wrote or edited 23 books of poetry, essays, and reportage, and logged thousands of miles giving poetry readings for elementary-school children. All told, the sum of his literary output includes almost 50 books; his work is reprinted in more than 300 anthologies.

David Thompson Watson McCord was born in New York City in 1897. McKinley was president, Sousa had just composed "The Stars and Stripes Forever," and streetcars were still horse-drawn. "I first came to Harvard," McCord wrote 60 years later, "by way of progression through New York, New Jersey, Oregon, Iowa, and Pennsylvania: one long lariat loop that finally caught the now-vanished tower of Memorial Hall. I ask myself tonight: what was it brought me here, and why have I never gone away? ...It was luck and pioneering in reverse. The Oregon Trail begins in Boston, you remember."

Between the ages of 12 and 15 McCord lived on an uncle's ranch on the edge of an Oregon wilderness. "I did not go to school, because there was no school," he recalled; instead, "I panned gold for pocket money." He also read. Emerson, Twain and Dickens, Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear were favorite authors, but "the real, the living poetry" in his life was the Bible, read aloud by his grandmother.

A 1943 watercolor by McCord entitled Equinox, Vermont, which he exhibited at the Century Association, New York City. A 1943 watercolor by McCord entitled Equinox, Vermont, which he exhibited at the Century Association, New York City. |

As a Harvard undergraduate, McCord "struggled to become a physicist," finally settling on literature as his field. He took leave to serve as an artillery officer in the final months of World War I, received his A.B. in 1921, and an A.M. in 1922. After three years as associate editor of the Alumni Bulletin, he was hired away by Joseph R. Hamlen '04, chairman of the newly formed Harvard Fund, later the Harvard College Fund. The new arrangement doubled McCord's $30-a-week salary, and, "best of all," left him "free to write books on my own, no questions asked." Oddly Enough, his first book, came out in 1926. "Some said it was good and some bad," he wrote in his fifth-reunion report; "I dare say it was."

In its first year the Harvard Fund brought in $123,544 for the College. McCord became executive secretary in 1927. Under his leadership, the fund raised a grand total of $15 million. Despite the national economic blight that began in 1929, the fund unfailingly registered annual participation increases during its first two decades. It was also the first alumni fund to reach 10,000 givers in a single year.

McCord took charge of the Alumni Bulletin when veteran editor John D. Merrill, class of 1889, died in 1940. While continuing to conduct the business of the College Fund, he revamped the magazine--enlarging its format, reducing its frequency from weekly to biweekly, expanding its coverage of Harvard books and authors, and introducing a regular editorial page and the "College Pump" column (see page 80). He stepped down as editor in 1946, but served on the Bulletin's editorial committee until 1966.

McCord saw the Bulletin through World War II. Despite the exigencies of wartime, the magazine's reports on the militarized University and the doings of alumni and students in service were detailed and comprehensive. The quality of the writing in those issues was a marvel. Especially notable were McCord's reportage on Winston Churchill's 1943 visit to Harvard, and a 1945 issue in memory of Franklin D. Roosevelt '04, LL.D. '29. The part-time editor also wrote strong editorials opposing prewar isolationism and reflecting on the postwar role of science and technology.

A staunch advocate of the "soft sell" in alumni relations, McCord wrote that "the language of request should always reflect the spiritual and intellectual quality of the institution it represents." Thus his stated belief in "using civilized language for a civil purpose," and his insistence on tasteful and painstaking typography and printing. To Brooks Atkinson '17, for many years the New York Times theater critic, McCord's fundraising letters and brochures were "little gems of humor, literature, and guile." McCord, an ardent angler, likened his low-key approach to "fishing with a barbless hook."

In recognition of his work in educational fundraising as well as in arts and letters, more than two dozen institutions gave him honorary degrees. In 1956 he was awarded Harvard's first doctorate in humane letters. The citation read, "Artist and poet, who personifies in his friendly stewardship Harvard's deep concern for people."

McCord later implied that if he had written the citation, "poet" would have come before "artist." "Poetry has really been my life," he told a Harvard Magazine interviewer in 1978. A master of many verse forms, McCord knew the power of short words and epigrammatic phrasing. One of his most quoted poems is also one of his briefest--"Epitaph for a Waiter," published by the New Yorker in 1933:

By and by

God caught his eye.

A close second, at least in Harvard circles, is "Man from Emmanuel," which first ran in the Harvard Lampoon at the time of the College's Tercentenary in 1936:

"Is that you, John Harvard?"

I said to his statue.

"Aye, that's me," said John,

"And after you're gone."

Not all of McCord's verse was brief--or light. "A Bucket of Bees," the longest poem ever published by the Yale Review, went on for eight pages. So did "The Dawn Stone," the 1938 Harvard Phi Beta Kappa poem.

By McCord's own reckoning, four-fifths of his 550 published poems were written for children. But as the late Howard Nemerov '41 observed, McCord was a "rare and wonderful poet who can delight equally...the listening children and the reading parent." To Clifton Fadiman, he was "both an acrobat of language and an authentic explorer of the child's inner world."

In the 1980s McCord lived at the Harvard Club of Boston with much of his 6,000-book library. He could often be found in the southwest corner of the lobby (which became known as McCord's Location), cigar in hand, regaling admirers with poems and anecdotes. Troubled by physical ailments in his mid nineties, he moved to Goddard House, a nursing home in Jamaica Plain. His books now take up two rooms at the Boston Public Library.

About Boston, a book of essays first published in 1948, was an expression of McCord's affection for the city. In 1973 the city reciprocated by honoring him as one of seven "Grand Bostonians." But stronger ties bound McCord to Harvard. "The Harvard ethos as a concentrate is powerful stuff," he wrote in College in a Yard, an anthology published in 1957. His Notes on the Harvard Tercentenary (1936) recounted an epic Harvard event in quintessential Harvardian prose. In later years, when McCord spoke of Harvard, he was fond of citing a favorite quotation from Willa Cather's My Antonia: "That is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great."

~John T. Bethell

Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

As executive director of the Harvard College Fund, in his office at #4 Wadsworth House, in 1963.Harvard News Office

As executive director of the Harvard College Fund, in his office at #4 Wadsworth House, in 1963.Harvard News Office A 1943 watercolor by McCord entitled Equinox, Vermont, which he exhibited at the Century Association, New York City.

A 1943 watercolor by McCord entitled Equinox, Vermont, which he exhibited at the Century Association, New York City.