Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

http:www.peabody.harvard.edu

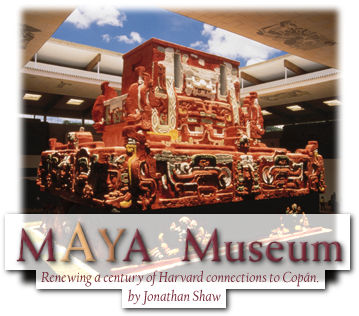

Giza has its sphinx. The Louvre has its entrance pyramid. Now the inscrutable, darkened maw of the Maya earth monster greets visitors to a new, world-class museum in Copán, Honduras. Beyond the entrance mouth, a dimly lit subterranean passageway betrays nothing of what lies ahead. Just as your eyes adjust to the darkness, the tunnel takes a turn to the left, and suddenly before you, dazzling and

The museum as seen from the air, half-buried in the earth. At ground level, trees will eventually conceal the structure. |

If the dramatic entrance to Copán's new sculpture museum reveals anything it is this: the museum is the creation of archaeologists, eager to share the mystery and excitement they experienced when the monuments housed here were first excavated. The real Rosalila, discovered in 1989 by Honduran archaeologist and Dumbarton Oaks Senior Fellow Ricardo Agurcia, is buried in a pyramid at the end of a series of narrow tunnels, whence relocation would be impossible. "The ancient Maya generally ripped out old buildings, used the rubble as fill, and built new buildings on the same site," says Harvard's William Fash, Bowditch professor of Central American and Mexican archaeology and ethnology. Rosalila was an exception. Packed with clay, then covered with rubble fill right up to the roof, the building was entombed beneath a new temple in an attempt to preserve it forever.

Preservation is a primary concern for the Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History (IHAH) and,

A sudden, fierce storm terrified workers reassembling this carved panel of the Central Mexican storm god, from above the hieroglyphic stairway. |

That's because archaeologists at Copán have for years struggled with a terrible dilemma, as Fash, who is director of the Copán Acropolis Archaeological Project (CAAP, see "Harvard Portrait," November-December 1995, page 73), explains: "Once they remove the dirt, deterioration sets in and they are racing against time." Some archaeologists, seeing no way to preserve all the sculptural fragments that had been unearthed, proposed reburial to protect them from further damage.