One day about four years ago, John Marshall’s youngest son came home from a class on climate change at Harvard Extension School and told his father, “Dad, you have to do something about this.” The 17-year-old (now a junior at Harvard) had been learning about rising seas—and countless other ecosystem impacts that will be locked in for thousands of years—from Hooper professor of geology Daniel Schrag. The prospect had shocked him. And the magnitude of the societal change required to deal with the problem was even harder to accept. It’s a disaster, he told his father, “and no one knows.”

John Marshall is not a scientist, a politician, or an engineer. He is an expert in the art and science of moving people. The former marketing executive, now a consultant, says his son locked him in the house for two days, and asked him to make some phone calls. “So I called a lot of my fellow ad execs and CEOs and said, ‘If I put an effort together on climate communications, would you dedicate resources on a pro bono basis?’”—the same way law firms donate a percentage of their legal services. “And I got a lot of yeses. And then I called Dan.”

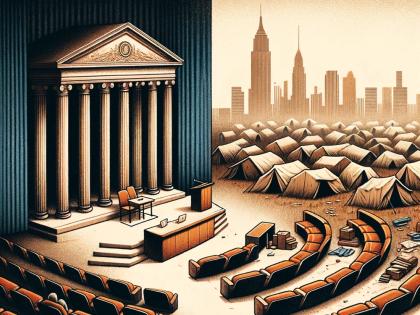

That conversation led Schrag and Marshall to launch the Potential Energy Coalition, a nonprofit dedicated to raising public awareness of climate issues in the United States. Surveys indicate that only between a quarter and a third of Americans care about climate change, says Marshall, lagging Europeans by about 20 to 25 percentage points. The goal of their nonpartisan organization is to change U.S. popular opinion by partnering with and providing marketing expertise to advocacy organizations aligned with their message.

The challenge is that climate change has become politicized: it is regarded as a progressive issue in the United States. “If I even say ‘climate change’ to conservatives,” Marshall explains, “visions of Al Gore [’69, LL.D. ’94] might start dancing in their heads and then I might not be able to make progress.” Popular opinion on the subject is like a barbell, he says. “For every message I issue that feels like it is part of a liberal agenda, I’m going to manufacture an opponent on the other side: all I’m doing is increasing the weight at the two ends of the bar, and I’m not changing the politics.”

On this issue, his research has shown, “People first pick their political identity, and then they choose whether or not they care about climate change.” Potential Energy aims to get the people in the middle to see it as an important, apolitical issue for humanity.

That job falls to a team of 25 people at Potential Energy, based in New York City, where all the modern tools of marketing have been custom-built to focus on climate change. Because it is hard to measure precisely how a person thinks, Marshall says, marketing involves a mosaic of techniques. The team exposes research panels and control groups to different messaging and logs their responses; it also runs digital tests on platforms such as Facebook and YouTube and watches who responds to particular stimuli. They track the effectiveness of campaigns they’ve launched by using polls to measure how people’s thinking about the issue is changing, he continues, seeking the “pockets of elasticity where you can actually move people” in a particular segment of the population. Every day, they solicit the thinking of a 100-person digital panel, sounding out their attitudes, needs, and fears. And then they test hundreds of variants of messages before millions of consumers via their digital lab. That’s how the team learned that using the phrase “climate crisis” is 26 percent less effective than using the less charged “climate change” for moderate Americans. They’ve received pushback from some of their more progressive funders for this sort of nuance, but Marshall is adamant that they follow the data: “My values aren’t important,” he says. “My data is important. I’m in the persuasion business; I’m not in the values business.”

The Potential Energy Coalition’s partners include some of the nation’s most effective marketing agencies.

Courtesy of John Marshall

The Potential Energy team also has access to all Marshall’s partners in the 200-agency network he has built, firms like Nielsen Media Research that perform dynamic polling, media companies such as Facebook and Univision, and advertising agencies like Weiden+Kennedy, famous for its work with Nike. “We’re using their tools, but specifically for climate change, and building databases of results,” he adds. “So, we’re a climate-change marketing engine” designed to make people aware of the issues, and the need to act on their convictions.

Schrag got involved in this project, which is unconnected to his duties at Harvard (where he directs the University’s Center for the Environment), because previous efforts to solve the climate problem have failed politically. The “dominant narrative” about addressing the climate problem “has been one of personal sacrifice,” that “it’s worth the cost to save the world,” he explains. “That’s a fairly liberal, collectivist argument” that he compares to the ineffectiveness of recycling. “You can’t actually behave your way out of the problem” individually, he adds. Complementary action at the government level is necessary. To prove his point, he invokes the pandemic shutdown: “COVID changed behavior more than anything you could ever hope to accomplish in the name of climate change.” Airplanes were grounded and cars parked as people stayed home. “And emissions went down just 8 percent, transiently. And they will come right back” post-pandemic.

“That tells you this isn’t a behavioral problem,” Schrag continues. “This is fundamentally a technological transformation problem. It’s not just about driving less or taking fewer airplanes. It’s about changing what airplanes are. It’s about changing what cars are. It’s about changing what power plants are. A lot of environmental groups are still pushing the fallacy that individual action is important, because it’s a way of getting people involved. But the most important individual action is to put pressure at the voting booth, and change policy quickly. That’s really what we need for a collective-action problem like this.”

Daniel Schrag

Courtesy of Daniel Schrag

Schrag joined forces with Marshall to precipitate such action at the polls. But Marshall says climate change is “one of the only markets I’ve seen where an individualized message—tailored for farmers, for moms, for Latinas, and for young people—outperforms a generalized message.” The reason? Climate change per se isn’t actually important to most voters, he explains. What matters to them “is the value of their homes, or the products of their farm, or their kids’ opportunities. And so you end up with a series of messages” targeting groups of five million to 15 million people, rather than a single crisis call to action.

That highly targeted messaging is driven by analytics. Plumbing the data, Potential Energy discovered that women are more persuadable than men, that Hispanics seem more movable than non-Hispanics, and that people in flood zones don’t appear any more movable than people on high ground. “You look at a population across a series of dimensions, and you try to find identifiable segments where you can get an outcome,” says Marshall.

What they don’t do is start with a message. That, he points out, is what the traditional “greens” do, organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund and the Sierra Club, whose supporters already understand the importance of climate change, and which certainly benefit from the work of Potential Energy at the broader policy level. “Our approach is to start with the people we want to move, and then figure out what message, and what messengers, will move them,” Marshall says. For example, when research showed that Latina mothers as a group, many of them independents or Republicans, are more likely to care about climate change, Potential Energy’s 501(c)4 sister organization teamed up with the Latino Victory Project (run by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s father) to launch their first major outreach last September. Called “Vote Like a Madre,” the campaign starred Jennifer Lopez, who urged mothers to make a pinky promise with their children that they would vote to support climate causes at the ballot box.

Market research shows that Latinos have a closer connection to nature, culturally, than other groups, Marshall explains. “They also talk to people outside the country a lot more, because many of them are recent immigrants. So, you call your cousin in Colombia, and they ask you about climate change, because they care more about it in Colombia than they do in the U.S. And finally, there is a family cultural aspect of caring about generations. All those things indicated to us that Latinos”—there are approximately 19 million Latino voters in Texas, Arizona, and Colorado—“were a really good audience.”

“But it’s not just Latina mothers” who care, says Schrag. “It’s all mothers.” He and Marshall helped launch the $10-million “Science Moms” national television, newspaper, and online video campaign, in which women scientists speak about their concerns in personal terms, worried about the future their children will inherit. “We provided all the support and the design and the creation of that video,” he says. Adds Marshall, “We’re spending our donors’ money”—supporters include the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, and the Quadrivium Foundation—“to run large-scale climate change campaigns, in partnership with other organizations that will benefit from it, and that are a fit with us.”

That means speaking not only to political centrists, but also the movable right. The team’s work with the American Conservation Coalition, a group of young conservatives who feel that they are on the wrong side of a generational divide over climate change, is an example. “We came up with a concept” and agreed to run a campaign with them, says Marshall. The group is happy because they have professional marketing expertise to help them work on their brand. “And we’re excited because they are good messengers.”

“My dream outcome,” says Schrag, “would be that 10 years from now, or even five years from now, Republicans and Democrats are furiously arguing about strategies for decarbonization. That would be transformative.”

The transformation begins with the people who work at Potential Energy, says Marshall. “Once they learn from Dan what is actually happening, they can’t sell credit cards anymore.” He adds that it is actually easy to engage partners in their efforts once they learn the truth. “We’ve had thousands of people working on this pro bono. Because once you know, you can’t go back. And with a little bit of effort, we could create a flywheel that will eventually engage all humanity. Because the advantage we have, over the billions of disinformation capitalists, is that we’ve got the truth on our side.”