Harvard has recorded its sixth consecutive budget surplus, some $298 million, up from a $196-million surplus in the prior year, according to the University’s financial report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2019, published today. From fiscal 2014 through the most recent year, the surpluses—accumulated at the end of the $9.62-billion Harvard Campaign, and during a period of continued U.S. economic growth and internal spending restraint—now total $769 million: an outsized tally that will make the University the envy of higher education. In the accompanying annual message from Harvard Management Company (HMC), chief executive N.P. Narvekar pulls back the curtain on the enormous changes that have been effected in the endowment’s investments since he arrived in December 2016, at what is effectively the midpoint of his envisioned five-year revamping of HMC’s organization and operations, culture, and, clearly, assets (see the section on the endowment below).

Highlights of the University’s fiscal year:

- Revenue increased nearly $300 million to about $5.5 billion (growth of 5.7 percent, compared to 4.3 percent in fiscal 2018 and 4.6 percent growth in fiscal 2017), in part reflecting slightly less stern restraints on distributions from the endowment—the University’s largest source of revenue (see discussion below).

- Expenses rose, too, by almost $200 million to $5.2 billion (3.9 percent, compared to 2.7 percent in fiscal 2018 and 3.9 percent in fiscal 2017, and a more robust 5.3 percent in the prior year).

- The result was an operating surplus of $298 million. Whether this reflects luck; or an abundance of caution about the economy, the outlook for endowment investment returns, or future federal support for research; or continued wariness after the Harvard’s severe financial crises of a decade ago—the institution is establishing a reputation for fiscal prowess.

President Lawrence S. Bacow’s introductory letter acknowledged the evident strength, but cautioned that “we, along with all of our colleagues in higher education, must be conscious of the challenges of our current climate.” He amplified:

The prospect of a long-running period of economic expansion coming to an end is very real. Uncertainty in federal research funding and the damaging tax on college and university endowments in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act [of 2017] also have the potential to hinder Harvard’s ability to grow investments in financial aid, teaching, and research across campus. Our challenge is to acknowledge these realities, advocate for policies and laws that will support our mission and continue to manage our finances prudently and thoughtfully so that we can make the investments in students, faculty, teaching and research that make a positive and lasting impact in the world.

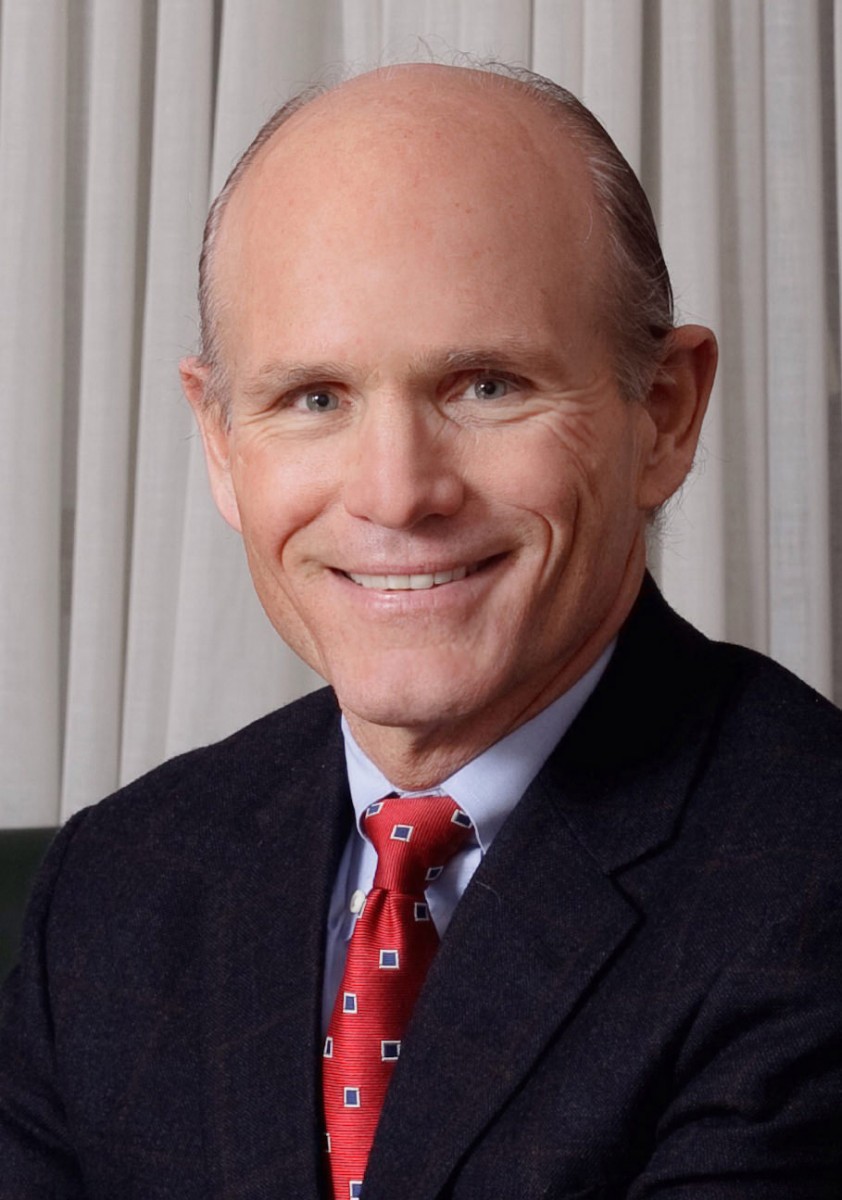

Thomas J. Hollister

Photograph by Paige Brown/Courtesy Tufts Medical Center

Similarly, in their overview, vice president for finance Thomas J. Hollister, Harvard’s chief financial officer, and treasurer Paul J. Finnegan (a member of the Corporation and chair of HMC’s board) gently pointed toward the pressures on higher-education revenues, the estimated $50-million provision for the new federal taxes during fiscal 2019, and the inevitable “end of the current economic expansion.” With a nod toward the latter, they pointed to the University’s continuing reduction of debt, increased cash holdings, and strengthened reserves (bolstered by those surpluses, of course). And although unspoken, they no doubt bear in mind that adjusted for inflation, the current endowment value ($40.9 billion) represents little, if any, progress from the value in 2008 ($36.9 billion), before the financial crisis—even as Harvard’s annual expenses have increased by about $1.5 billion during that period. For now, they can revel in the institution’s ability to increase spending on research, financial aid, teaching, and faculty—all while bolstering reserves.

The University’s sources of revenue remained substantially unchanged during the year:

- endowment distributions, 35 percent;

- net tuition and other sources of revenue from students, 22 percent (up one percentage point);

- sponsored-research support, 17 percent, and current-use gifts, 8 percent (each up in absolute dollar terms, but down a percentage point as a share of total income compared to fiscal 2018); and

- other income, 18 percent of revenues, up a point.

These and other points are made clearer in a report format that is somewhat jazzed up graphically compared to prior years—but with somewhat less detailed explanatory text.

The Financial Year That Was

Revenue. Operating revenue increased nearly $300 million, to about $5.5 billion. Principal areas of growth were:

- student income, up nearly $80 million (about 7 percent), to $1.2 billion. The report no longer provides separate figures for undergraduate, graduate and professional, and continuing and executive education revenues—but the text notes that the latter increased 12 percent, making this a half-billion-dollar business, a distinguishing feature of Harvard’s operations and finances. Those fees now essentially equal net revenue (after financial aid) from undergraduate and graduate degree programs; and

- the endowment distribution, up nearly $90 million (4.7 percent), to a bit more than $1.9 billion. In fiscal 2018, the Corporation held the distribution flat per unit of endowment owned by each school, and suggested that distributions could increase within a range of 2.5 percent to 4.5 percent annually for fiscal years 2019 through 2021—beginning with 2.5 percent in 2019. The budgeted modest growth in distributions reflects weak performance earlier in the decade (a -2.0 percent investment return in fiscal 2016) and, perhaps, internal recognition of the challenges involved in remaking HMC and redeploying its investment portfolio (see discussion below). This year’s larger distribution reflects incremental endowment earnings on and distributions from gifts: new endowment units as a result of largess from The Harvard Campaign and subsequent philanthropy. (The per-unit endowment distribution in the current fiscal year 2020 is again budgeted to increase 2.5 percent.)

Other sources of increased revenue included sponsored research ($937 million, up from $914 million in fiscal 2018). Federal direct grants in fact decreased modestly, but increased “indirect” cost reimbursements (for recovery of overhead expenses) more than offset that decline. Non-federal sponsors (foundations, corporations, and individuals) boosted both direct grants and their funding of indirect costs. (Federal reimbursement rates for indirect costs far exceed those from non-federal research support, so the shift in the mix of funding is a slight negative for Harvard.)

Other revenue, a catch-all category, also chipped in significantly, increasing more than $80 million (13 percent), to $772 million, propelled by a $43-million bump in royalty payments for use of intellectual property.

In effect, essentially every category of unpredictable revenue—continuing and executive education, non-federal sponsored research, and current-use giving (see discussion of philanthropy below)—performed strongly, yielding a surprisingly large surplus, given spending growth that conformed to budgeted expectations.

Expenses. The University’s spending increased nearly $200 million, to $5.2 billion. Compensation—salaries, wages, and benefits—accounts for half of expenditures, and rose 4 percent: about twice as fast as in fiscal 2018. Salaries and wages increased 4.9 percent, also accelerating from the prior year, reflecting both pay increases and additional employees (many of them on term agreements related to research funding or in growth areas like continuing and executive education). Employee-benefit costs declined slightly. Costs for active employees have been contained by changes in health plans (increased deductibles and coinsurance), which may also induce spouses and partners to choose non-Harvard coverage where offered. Benefits for retirees have come in below budgeted expectations. Moreover, the benefits line item is subject to annual accounting adjustments reflecting changes in prevailing interest rates; this year, that reduced the reported expense.

Balance sheet and capital items. The largest capital-spending program in Harvard history rolled on apace, with $903 million invested in fiscal 2019, just marginally less than the record $908 million during fiscal 2018 and $906 million in the prior year. Construction in progress remains nearly $1.3 billion, down only slightly from fiscal 2018. As projects have been completed, new ones have begun.

The Lowell House renewal, one of the megaprojects, is now complete; it is featured on the cover of the report (shown above). The Allston science and engineering center opens in the fall of 2020. Its commissioning raises questions, thus far unresolved, about how the University and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), which is to occupy the center, will divvy up the substantial operating and depreciation costs associated with the facility—the dreary downside associated with any exciting new quarters. This SEAS statement on the issue gives a flavor of the back-and-forth:

When SEAS occupies the SEC (and a portion of the adjacent 114 Western Ave.) in Allston next year, we will assume significantly higher operating expenses associated with the use of these University-owned buildings. Obviously, this has been on our radar for several years and is reflected in our long-term financial modeling. SEAS leadership has been in conversation with the central administration at the highest levels to address this issue and we are encouraged that the University understands, and is prepared to work with us, to find a solution to the financial challenges of the new campus.

The University, in its role as prospective landlord, remains coy about its terms.

Adams House renewal is under way, another major undertaking, and the renovation of the Divinity School’s Andover Hall is proceeding as well. There is plenty of Harvard work for the building trades.

Looking ahead, with the completion of some of those major projects, fueled by the capital campaign, capital spending may begin to decline after this year. The budget surpluses, and depreciation (now nearly $400 million annually), provide a source of funding for construction. Their combined magnitude, and a less ambitious capital program, might enable the University to avoid additional borrowing—an eventuality for which it had previously been preparing. With debt outstanding continuing to decline (currently $5.2 billion, down from $5.3 billion in fiscal 2018), interest expense decreased modestly during the year, too, to $184 million. Chipping away at those totals, rather than seeing them increase, would no doubt make the CFO and treasurer happy.

Philanthropy. Even beyond the operating surpluses Harvard has reported, the strength of the philanthropic support it receives continues to astonish. At the conclusion of fund drives, like The Harvard Campaign (which ended on June 30, 2018), current-use giving typically tails off as donors catch their breath. And indeed, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences reported a 14 percent decline in these most flexible, useful funds.

But the University as a whole logged a modest increase in current-use gifts, to $472 million—a testament to deans’ fundraising appeal, the efficacy of their development teams, excitement about the new president, or whatever. The timing of one large payment on a current-use pledge, late in the financial year, apparently bolstered the total. But pledges for current-use gifts increased by nearly $200 million from the end of fiscal 2018—along with pledges for non-federal sponsored research (up about $100 million) and construction and other uses (up about $70 million). Perhaps this is an echo of the campaign, but it is impressive. Fundraisers worldwide will want to know Harvard’s secret.

Even more impressive, huge gifts have continued to pour in (four nine-figure gifts reported in fiscal 2019 are listed here)—and the data in the back of the annual financial report suggest that that is only the tip of the iceberg. In the years following a capital campaign, pledges are typically fulfilled over time. From the end of fiscal 2017 to the end of fiscal 2018, pledges for endowment gifts decreased by about $140 million, to $935 million. Assuming that further payments were made during fiscal 2019, the increase in this balance to $1.5 billion as of this past June 30 suggests some stupendous gifts yet to be unveiled—or at very least, a lot of significant ones in the pipeline. (Only one of the four gifts listed above is for endowment.)

An accounting change also bolstered reported pledges, by perhaps $100 million; but the larger story remains the $900-million-plus increase in pledges receivable.

In prospect. Whatever political problems Harvard’s strong financial position may elicit, it is a good problem to have in an uncertain, volatile world. Costs are guaranteed to rise as expensive new facilities open, financial aid increases, and research in nearly every discipline requires more equipment, computation, and technical support. The Graduate Student Union negotiations may well result in higher costs for that large cohort of workers. The new Massachusetts family-leave benefit will increase benefit costs, even if the University secures an exemption by making comparable provisions for employees within its programs.

And looming over the University is the continuing transformation of the endowment, the performance of which is the foundation of Harvard’s financial model.

The Endowment: Anchors (Partly) Aweigh

Narvekar’s letter on HMC—amplifying the late-September announcement that it earned 6.5 percent on investments during fiscal 2019—is a revealing peek into:

- HMC’s substantially redeployed portfolio;

- the steps taken to effect the most significant changes in the investments; and

- the longer-term opportunities and challenges, both in the next couple of years and as the new HMC organization fully effects its investing strategy over the next five to seven years.

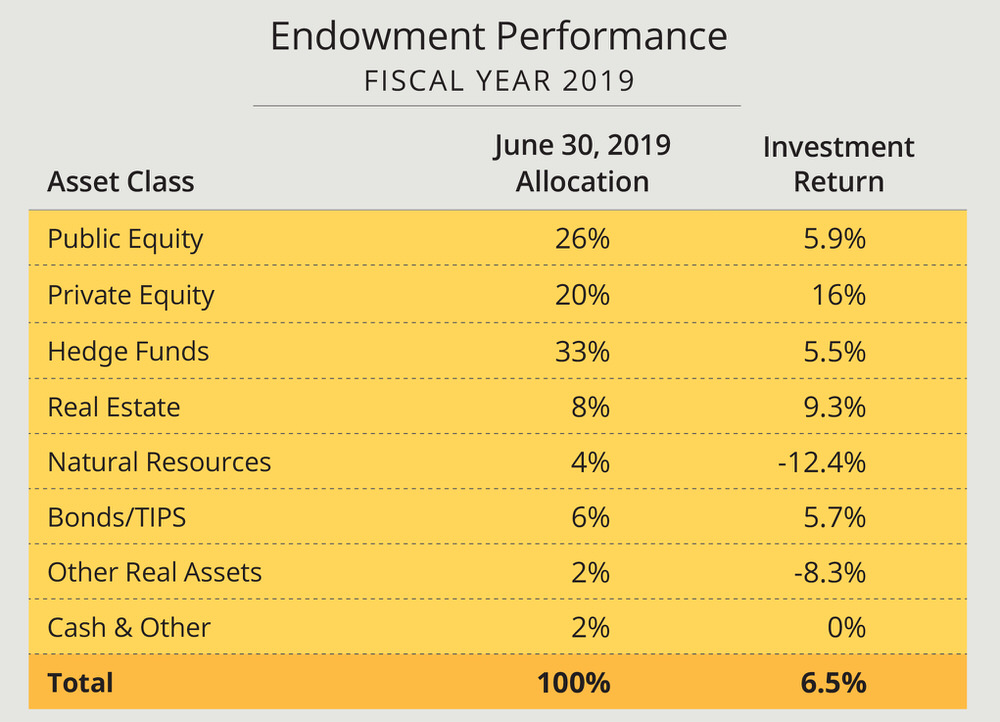

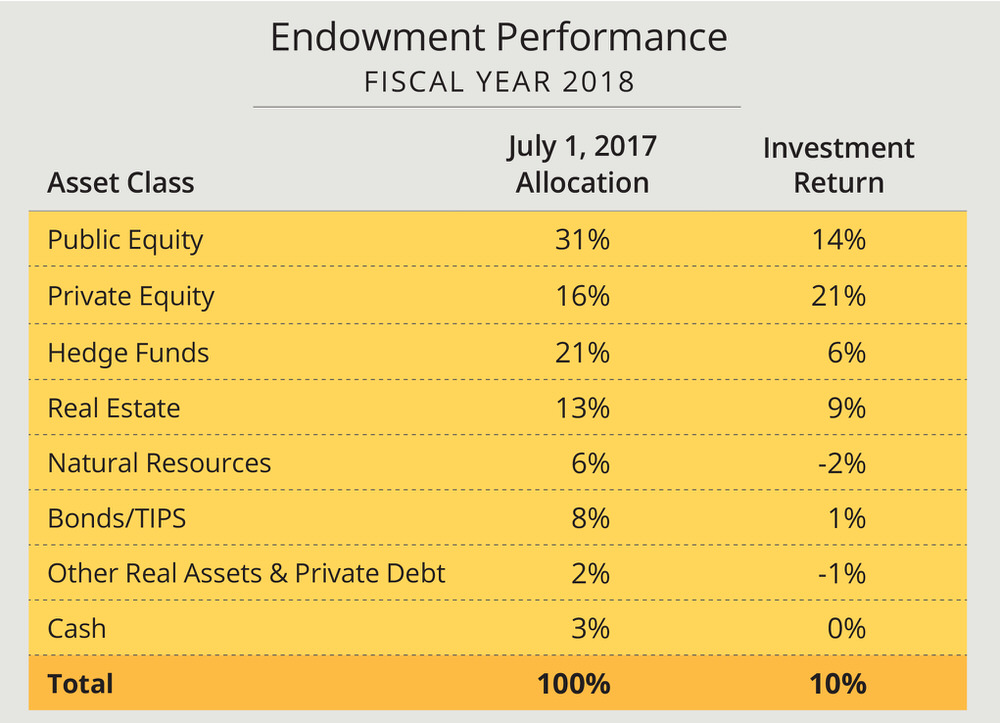

The assets, redeployed. The letter includes an exhibit displaying HMC’s asset allocation as of the end of fiscal 2019, and performance by class during the year. The data, shown here, reveal that private-equity holdings again produced the standout return: 16 percent in fiscal 2019, vs. 21 percent the prior year. Narvekar is rigorous about emphasizing long-term returns (typically, a decade, to capture a full economic and investment cycle) and the endowment’s performance as a whole. He nonetheless observed that on a combined basis, HMC’s most liquid assets—public equities and a majority of the hedge-fund holdings, nearly 60 percent of the total portfolio—outperformed their blended benchmark by an annualized 2.25 percentage points during the past two years, a result he characterized as “very good, albeit not excellent.”

These details point to a larger shift in tone. His prior annual messages explained HMC’s wholesale, internal reconstruction. This year, in effect, he has pivoted to assessing what has been wrought.

The outstanding takeaway is the almost-breathtaking redeployment of endowment assets. Comparing the June 30, 2019, distribution with the July 1, 2017, exhibit published last year (see below):

- natural-resources have been slashed to 4 percent of holdings, down from 6 percent in the prior distribution (and 10 percent in fiscal 2016);

- real estate now comprises 8 percent of investments, down from 13 percent in the prior report (and 14.5 percent in fiscal 2016); and

- hedge funds (mostly liquid) have risen to one-third of total assets, up 12 percentage points from the previously reported 21 percent (and 14 percent in the fiscal 2016 allocation): a swift, massive change in an overall investment pool (including the $40.9-billion endowment) now totaling $46 billion.

Public equities, also highly liquid, have come to comprise 26 percent of the current allocation—down from 31 percent reported as of July 1, 2017, and 29 percent in fiscal 2016.

And private-equity holdings—down to 16 percent in last year’s report—have now increased to 20 percent of assets: in line with the fiscal 2016 allocation, but indicative both of a restructuring of the holdings Narvekar and his team inherited, and of the time it takes to reinvest well in this key, but illiquid, asset class (see discussion below).

Addition by subtraction. Narvekar documented the costs of effecting the transition in the portfolio to date. Legacy natural-resources investments (at this point, principally timber and agricultural land) have produced “persistent negative returns.” In fiscal 2017, during the first six months of his tenure, “we were forced to write-down or write-off approximately $1 billion of these investments”—reducing the values of some assets and taking total losses on others. An additional $100 million of assets were written down in fiscal 2019. Beyond those losses (which would have been incorporated especially in HMC’s investment return of 8.1 percent reported for fiscal 2017), HMC sold another $1.1 billion of natural-resources holdings, and anticipates selling a further $200 million in the current fiscal year.

Despite these sweeping actions, Narvekar noted that remaining natural-resources assets would have yielded a return of -7 percent even without that fiscal 2019 write-down. And of these and some other assets, he warned that even after the write-down and further sales, “[T]here are still many illiquid anchors weighing down the portfolio and our performance. Put another way, parts of the legacy portfolio do not have a prospect of generating a return commensurate with the risk and the illiquidity entailed, and may not provide a return at all.” Although the problem has clearly lessened, it “remains a significant challenge and a major priority” for an extended period.

He did not detail other sales, but HMC is also understood to have disposed of a significant volume of private-equity, real-estate, and other assets since Narvekar became CEO—probably more than $1 billion; and to have written down (or written off) a lesser total of other miscellaneous holdings (again reducing investment returns). During fiscal 2018, a robust year for many endowments, HMC reported an investment return of 10.0 percent: still behind many peers’ results, but better than in 2017, perhaps in part reflecting the effects of those large reductions in the value of underperforming assets.

Updated October 25, 2019, 11:25 a.m.: In a statement made available after publication of the annual financial report and this article, HMC board chair Paul Finnegan said, “The HMC board and I are keenly aware that Narv and his colleagues inherited a very difficult situation, even more so than is generally recognized. We are extremely pleased with the progress made, particularly in such a short period of time.”

Although Narvekar focuses on HMC’s performance, not that of peers, and the fiscal 2019 return of 6.5 percent trailed the prior year, he no doubt takes at least some satisfaction from edging such traditionally outstanding performers as Princeton and Yale, whose 2019 returns decreased sharply (to 6.2 percent from 14.2 percent in fiscal 2018 percent for the Tigers, and to 5.7 percent from 12.3 percent for the Eli team).

N.P. Narvekar

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University

The road ahead. For now, funds made available from asset sales and new cash have clearly been directed to hedge funds, where they can be put to work swiftly. But that is not Narvekar’s ultimate aim for HMC’s asset allocation. His principal concern, consistently expressed since his arrival, is that Harvard is under-invested in private equity: “HMC’s allocation to buyouts, growth, and venture capital continues to be low relative to what likely makes sense for Harvard.” That case rests not on the recent high returns (indeed, “recent performance, and specifically the valuation environment, serve as a restraint”). Rather, private-equity assets are a likely source of greater-than-market returns over time (in part in compensation for their illiquidity), and provide a useful way to deploy leverage (borrowing by companies within a private-equity fund manager’s portfolio) without recourse to the endowment itself.

In fact, a good part of HMC’s long-term underperformance during the past decade might reflect relative under-investment in private equity. To some degree, that may have resulted from the management company’s prior division into internal asset-management teams, each engaged with its own class of assets, and each making a claim on investible endowment funds—thus underemphasizing an optimal allocation for the portfolio as a whole. And the fallout from the financial crisis of 2008-2009, when major losses within the endowment and elsewhere in the University forced Harvard to be more cautious financially, kept HMC from making many illiquid investments for several years. Those assets have produced outsized results for other endowments during this decade. Per Narvekar, “some of the big IPOs [initial public offerings] of this past spring were backed by venture funds with vintage years from 2008-2013. Harvard did not participate in those funds in that era and therefore did not benefit significantly from those rewards in fiscal year 2019. Indeed, this is a long-term game.”

Just how long term? “Early in my time, we modeled it to take 7-9 years to attain a meaningfully higher allocation to private equity in a prudent manner”: selecting the right managers, diversifying the investments over time to ladder their maturities, and being patient during an “aggressive valuation environment.” That suggests another five to six years to achieve a targeted level of private-equity investment, and a subsequent multiyear period to harvest the results. So that pool of liquid equity equivalents—public stocks, and hedge funds—may be outsized for some time.

Assessing risk tolerance. The changes in organization, culture, and incentives that Narvekar earlier outlined as essential for long-term performance have been made and, he wrote, “we have made good success” in implementation. The organization now consists of a small, highly professional investment team, which oversees the assets as a whole—rather than aggregation of separately managed silos divided by asset class. The focus is on performance over an economic and market cycle. And HMC staff members’ compensation incentives are tied to the endowment’s consolidated results.

Still nascent, however, is a discussion between HMC and its client, the University, about Harvard’s tolerance for investment risk. An HMC board subcommittee, chaired by Safra professor of economics Jeremy C. Stein, on which Thomas Hollister (an HMC board member) also serves, has begun a deep dive into the subject. As Narvekar frames the issue:

We are focused upon and aware that HMC generally takes lower risk and, therefore, will likely generate lower returns than many peers over a market cycle. During these discussions we will determine if this approach is appropriate or not. The tradeoff is of course higher returns versus a less volatile revenue stream. Perhaps stating the obvious, higher returns lead to a larger endowment in the long run, while lower volatility can be helpful in budgeting for an institution with significant fixed costs.

These are hard issues. Princeton and Yale (excluding revenues from its academic medical center) are much more reliant on endowment income to pay for operations than Harvard is—and, perhaps counterintuitively, have traditionally operated higher-risk investment portfolios than HMC’s. And within Harvard, the endowment is run as a single portfolio with a single risk profile—but the academic units receive as much as 87 percent of operating revenue from endowment distributions (Radcliffe Institute) to as little as 18 percent (the Business School and the School of Public Health). Is this wise—or might the different units’ investments be buffered with a cash reserve accumulated in advance, or boosted by leverage to suit their distinct needs? How might the effects of a downturn be parceled out to operating budgets in subsequent years? (Harvard, Yale, and other schools follow different formulas to apportion the pain.) These questions, and more, need to be sorted out for the University’s long-term financial wellbeing.

Narvekar forecasts a two-year process of probing these matters before HMC and Harvard arrive at some policy, and then a period of adjustment to effect it. In the meantime, the protracted work of investing funds in private equity can proceed in a measured way. In a sense, the decision to reduce real-estate assets, and to downsize the natural-resources portfolio, has created some breathing room during these deliberations: both asset classes are characterized by illiquidity and significant risks, and so the endowment has become relatively more liquid and less risky as a result of these reallocations.

A good thing, too, because in a prolonged period of low interest rates worldwide, and high valuations for many kinds of investments, the challenge of earning returns commensurate with the University’s financial expectations and academic aspirations is significant. “Our team is well aware that meeting those needs requires continuous improvement and overcoming the challenges” previously outlined, Narvekar concludes. “I remain highly confident in our ability to do both.”

A final note on endowment dynamics. The annual financial report provides information on the endowment’s underlying growth, resulting in the fiscal 2019 total value of $40.9 billion. It is now possible to update the estimates made when the fiscal 2019 investment return was unveiled. That report suggested that:

- Investment returns were about $2.6 billion; the actual figure was $2.3 billion.

- Operating distributions were $1.9 billion—a fit with the $1.9 billion actually disbursed.

- Gifts for endowment rose to $1 billion: the actual figure decreased to $613 million (from $646 million in fiscal 2018).

No estimate was made for other one-time “decapitalization” distributions; the total reported was $32 million, down modestly from $46 million in fiscal 2018.

The major variance from the estimate published earlier was the extraordinary growth in pledged gifts for endowment (see discussion above), which rose to $1.5 billion from $935 million. Pledge balances are included in the University’s reported endowment total.

••••

In their preface to the annual report, Thomas Hollister and Paul Finnegan observe, “The wisest thing Harvard can do with its financial resources is to allocate them to maximize excellence in its teaching, research, and scholarship.” Doing so necessarily involves balancing and trading off current spending versus saving for future. Much the same sort of balancing arises as HMC and the University consider the institution’s tolerance for risk and the sort of investment portfolio it ought to have.

Whether one chooses to view Harvard’s recent surpluses as large in absolute terms, or small relative to an institution with a $5-billion-plus budget, it is surely fortunate relative to much of the rest of higher American education—but not without other kinds of challenges at the present moment.

Read the full text of Harvard’s annual financial report here. Read a Harvard Gazette story about the fiscal 2019 results—a Q&A with executive vice president Katie Lapp and CFO Thomas Hollister—here.