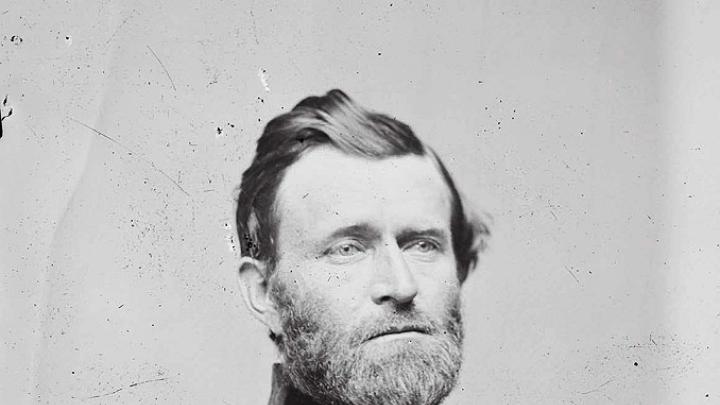

By late 1863, most of the major Civil War battles in the West—Shiloh, Stones River, Port Hudson, Vicksburg, Chickamauga, Chattanooga—had been fought. Union forces had the upper hand. Much of the credit for the success went to Major General Ulysses S. Grant, whose aggressiveness especially appealed to President Lincoln, long frustrated by the cavalcade of hesitant, high-maintenance generals who had commanded the Army of the Potomac in the East since 1861. In March 1864, the rank of lieutenant general (last held by George Washington) having been revived for the purpose, a newly promoted Grant assumed command of all Union armies.

War-time sketch credited to German immigrant and Union Army captain Adolph G. Metzner

Sketch by Adolph G. Metzner/Library of Congress

In December, Grant had summoned senior officers to Nashville to discuss the winter campaign. One night, at the suggestion of William T. Sherman, they went to see Hamlet. The mood was raucous from the start, the audience full of soldiers on their way to or from leave. The officers were sitting incognito in the balcony when, according to one, Sherman started complaining loudly that the actors were butchering the play. When Hamlet picked up Yorick’s skull, a soldier at the back bellowed, “Say pard, what is it, Yank or Reb?” The audience erupted, and Grant said, “We had better get out of here.”

The anecdote nicely illustrates the difference between the excitable, voluble Sherman and the calm, unobtrusive Grant. It is also deeply suggestive. Contemplating human remains was nothing alien to that audience. The skull prompts Hamlet’s unflinching meditation on the fate of even the greatest heroes: Alexander’s dust might seal a beer barrel, while Caesar’s clay “Might stop a hole to keep the wind away.” In the Norwegian Fortinbras, willing to bury 20,000 soldiers to secure a worthless piece of land, Hamlet sees a puffed-up prince hungry for martial honor. Causes, for Hamlet, are never ancillary: with his dying breaths he commands Horatio, “report me and my cause aright.”

Grant’s Tomb, New York City

Photograph by Cal Vornberger/Alamy Stock Photo

Grant, like Hamlet a careful parser of causes, readily distinguishes in his Personal Memoirs, finished days before his death from cancer, between the cynical political motives that sparked the Mexican War and the just principles that animated defense of the Union. He states unequivocally in his conclusion: “The cause of the great War of the Rebellion against the United States will have to be attributed to slavery.” Its perpetuation was “one of the worst [causes] for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

Terse, cool, free of melodrama, Grant’s book is an anomaly among the era’s many Civil War memoirs. To a perhaps surprising degree, Grant shared Hamlet’s mistrust of a particular kind of martial honor. Although he possessed physical courage and recognized it in others, he prized “moral courage” above all. He was suspicious of braggarts, “men who were always aching for a fight when there was no enemy near,” and self-deprecating. Yet even as he finished his memoir, its story was being eclipsed, just as Hamlet’s doubts are drowned out by Fortinbras, who arrives to take over Denmark and bury its prince with a wildly inappropriate soldier’s funeral. The revisionist Civil War narrative—glorifying the Lost Cause through song and story, textbooks and statuary; cloaking with chivalric ritual and romance the doctrine of white supremacy; abstracting the battle from the cause; sacrificing African-American rights to what Frederick Douglass called “peace among the whites”—created a hero who still infatuates the American mind: the knight-errant, Robert E. Lee.

An 1888 collectible from the "Great Generals" series

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Public Domain

Grant became a casualty of this new narrative. At his death he was arguably the most famous man in America and the most recognizable American in the world. In 1900 President Theodore Roosevelt, A.B. 1880, LL.D. 1902, launched his predecessor into the heroic firmament: “mightiest among the mighty dead loom the three great figures of Washington, Lincoln, and Grant.” And there he stayed, briefly, until revisionism did its work, and Grant, LL.D. 1872, became a butcher, a drunk, a serial failure, a dupe of the Gilded Age’s greediest men.

The season of Ulysses S. Grant is now upon us. Biographies by Ron Chernow and others have appeared, as have new editions of Personal Memoirs. This spring, a statue of Grant will be unveiled at his alma mater, West Point. How, amid such welcome attention, can we celebrate Grant without turning him into the kind of hero he mistrusted? Articulating the particular challenge of Grant’s heroism in 1886, Matthew Arnold described him as “free from show, parade, and pomposity; sensible and sagacious; scanning closely the situation, seeing things as they actually were…never flurried, never vacillating, but also not stubborn, able to reconsider and change his plans.” Even so, he insisted, Grant “is not to the English imagination the hero of the American Civil War; the hero is Lee.”

What Arnold said of the English imagination, W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95, discerned in the American. To find “greatness and genius” in Lee’s demeanor, lineage, and generalship ignores the “terrible fact” that he fought to preserve slavery. It was the South’s trial, Du Bois wrote in 1928, that the courage of its heroes would always “be physical…not moral…their leadership…weak compliance with public opinion,” not “costly and unswerving revolt for justice and right.” There could be no exoneration for Lee, “the most formidable agency” the country produced for preserving “4 million human beings” as “goods.” It is the trial not just of the South but of the United States writ large that it chose to fall in love with Lee and a Lost Cause as opposed to the necessary work of Grant’s cause: recognizing four million “goods” as human beings.