Like many writers, Shane McCrae, J.D. ’07, remembers clearly when he first took an interest in words, when the urge—and then the need—to write first grabbed him. It happened all at once, on October 25, 1990. He was 15 years old, living in Aloha, Oregon, and that afternoon his high school screened an after-school special, about a young man who committed suicide. One warning sign, the film explained, was that he’d been reading poetry. “A lot of Sylvia Plath,” McCrae recalls. In a funeral scene, one character quoted from Plath’s “Lady Lazarus”: “Dying / Is an art, like everything else. / I do it exceptionally well.” Those lines went through McCrae like an electric current. He wrote eight poems that day. By the next year, he’d decided to become a poet.

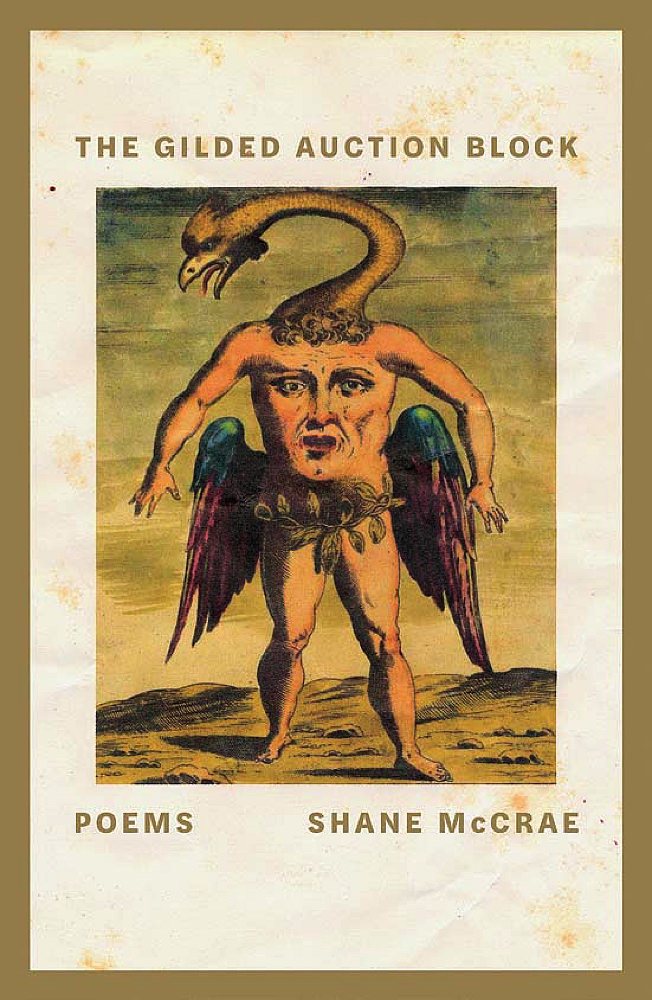

He’s now an “alarmingly prolific” one, as a reviewer put it. In the past seven years, McCrae, a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop who teaches creative writing at Columbia, has produced six books and three chapbooks; 2017’s In the Language of My Captor, was a National Book Award finalist. His newest collection, The Gilded Auction Block, will be released in February 2019 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “Every time I’ve published a book, I’ve thought I should slow down, but I honestly don’t know how,” he says. “It doesn’t really feel so fast to me. My experience is, lots of silence punctuated by occasional stretches of happiness during which I’m writing.”

The velocity of his output is matched by a propulsive intensity. His poems hurtle down the page, in fragments and echoes and dislocations, communicating amazement or horror or hunger or vulnerability with brutal precision. His syntax doubles back on itself; words are fractured, lines interrupted; sometimes the whole enterprise races to a halt. His poem “Claiming Language” ends this way:

I want a different language / Lord not

a claiming language / I want a languagelike the language Lord

our bodies use to free each other

“McCrae writes as though he’s trying to stitch the world back together,” critic Jonathan Farmer suggested in a 2015 Slate review.

Perhaps he is. McCrae’s poems often revisit his childhood. When he was three years old, his white grandparents kidnapped him from his black father—whom he would not see again until he was 16—and raised him to believe that his father had abandoned him. They denied that he was black, even as they punished him for his blackness (“I always knew,” McCrae says now. “There’s a kind of dual consciousness….I knew it, but also didn’t know.”). His grandfather was a violent and physically abusive white supremacist; McCrae’s poetry recounts sexual abuse by other boys.

By the time he and his classmates watched that after-school special on suicide, McCrae was five years into a “serious existential commitment” to give up on life. He had failed every grade from the sixth grade on. Hearing Plath, though, a world opened. He became a regular at the school library, poring over books about poets’ lives, reading Ann Sexton, Linda Pastan, and, of course, Plath. “I became really profoundly obsessed,” he says. “I had this idea that poetry was either going to be the key to the rest of my life, or there just wasn’t going to be a key.”

He didn’t finish high school. At 18, McCrae became a father and earned his GED. At 19 he and his first wife married. (He now lives with his current wife, Melissa, and their 8-year-old daughter, and is close to his two children from previous marriages.) At 21 he started community college and afterward transferred briefly to the University of Oregon, where he solidified a budding interest in the early canon. “It turns out that my favorite poetry is Elizabethan and Renaissance English poetry,” he says. “Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene has been necessary to me, to my conception of myself, of the world, of art.” For all its radical syntax and raw emotion, McCrae’s poetry adheres to metrical strictures that date back 500 years: “I had this rule that I would not do anything metrically that Sir Philip Sidney”—who wrote The Defence of Poesy in 1579—“would not have recognized as valid.”

McCrae finished his undergraduate degree at Linfield College, a small liberal-arts school with a creative-writing major, and from there went to Iowa’s M.F.A. program and on to Harvard Law School (“I was good at logic-ing,” he says, “and I thought I might become a lawyer”). While in Cambridge he took Boylston professor Jorie Graham’s poetry workshop, which transformed his writing from free verse “that read like everybody else’s,” to a style that felt truer; its strangeness cracked open something deep and abundant. “That’s when I started to write much more quickly.”

Historical consciousness weighs on all McCrae’s poetry, worlds burdened by the presence of an immutable past, and questions about how to live with that. His 2013 book, Blood, is a collection of slave narratives, searingly rendered in the first-person. “Who do I got to kill / to get all the way free,” asks the book’s final poem, “After the Uprising.” The Gilded Auction Block, the newest volume, considers life in the age of Donald Trump (“Sonnet for Desiree Fairooz Prosecuted for Laughing at Jeff Sessions’ Confirmation Hearing,” is the title of one poem), but also the long history that made the age of Trump possible (“Remembering My White Grandmother Who Loved Me and Hated Everybody Like Me,” is another). Several poems address an “America” that seems at times imaginary: the American dream, the American idea, “the America that America sees when it looks in the mirror,” he says. The 40-page “Hell Poem” considers “our capacity for accepting and normalizing the terrible.” The book ends with a poem called “After the Skinny Repeal is Voted Down”—a reference to last year’s Senate attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act—in which the speaker overhears four strangers at a Wendy’s talking about their grandchildren’s lives: “I breathe the words they say to each other / We live and die apart together.”

McCrae sees a new golden age of political poetry dawning now, intertwined with confessional poetry. “It has to do with identity,” he explains; poets from marginalized backgrounds “are asserting the right to confess identity-based harm they have suffered, or celebratory joy. They are asserting the value of their stories.” And like McCrae, they are finding that their words have power.