The Vietnam War era at Harvard is largely remembered as a time of resistance. In the late 1960s, students burned draft cards, occupied University Hall, and helped drive ROTC off campus. But before the anti-war movement became daily news in The Harvard Crimson, one undergraduate—Carl Thorne-Thomsen ’68—engaged in a personal and uncommon act of protest.

Those who knew him describe someone smart and athletic, enthusiastic and genuine, funny and at ease with himself and others. Though his humor often masked it, he also had a thoughtful side, writing in a high-school friend’s yearbook, “Perhaps I do not seem serious…but nonetheless I am.” Above all, Thorne-Thomsen possessed a sense of justice that led him to fight in a war he did not believe in.

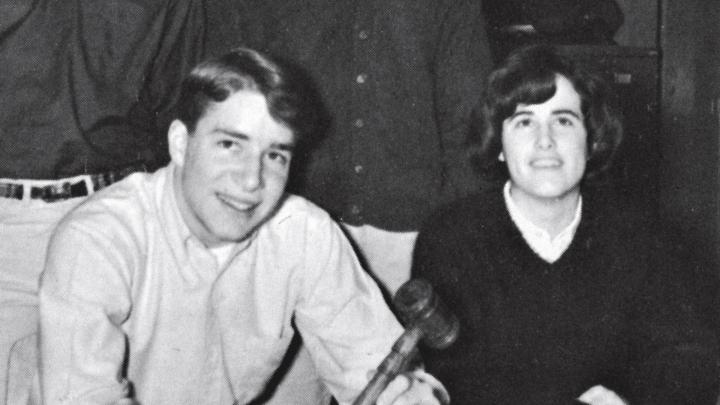

The fourth of five children in a politically conscious family, he grew up north of Chicago. At Lake Forest High School, he earned academic honors, played the cello, and was a standout athlete. His best friend, Jim Kahle, recalls summers when “we would go sailing, swimming, and play wiffle ball during the day and at night engage in solving the world’s problems.” As student-council president, Thorne-Thomsen demonstrated his democratic values by working to eliminate a grade-point requirement for future officers.

At Harvard, the six-foot Midwesterner tried out for freshman crew and became one of two first-time oarsmen in the 1965 undefeated lightweight boat, rowing in the number-five seat. Teammate Chris Cutler remembers an exceptional athlete who “brought humor and joy to the boathouse.” Bill Braun adds, “Carl always wanted to do more than his fair share. You never had to look over your shoulder to see if he was pulling his oar.”

But the Dunster House resident had more on his mind than rowing. With the Vietnam War escalating, concern about the draft led students to forgo leaves of absence, join the Peace Corps, and apply to graduate school. According to the 1966 Harvard yearbook, many considered military service in the unpopular conflict to be a “waste of time” and “the work of a high-school dropout.”

Thorne-Thomsen saw it differently. He believed it was unjust for him to remain sheltered at Harvard while the government sent poorer, less well-educated young men to war. In late 1966, he told his friend Linda Jones (Docherty), who had served with him on student council, that he was thinking of leaving college; she recalls him saying, “Talk me out of it.” She couldn’t, nor could the few family members and friends in whom he confided. “He scorned that student deferment,” says his oldest brother, Leif. Thorne-Thomsen withdrew from Harvard in his junior spring and was drafted shortly thereafter. Rejecting the offer of a hiding place in Canada, and a safer post in the Pentagon, he told his father, “I have to do this.” His mother, who begged him not to go, wrote later that his decision exemplified “the qualities I loved most in him. He was perceptive, he hated unfairness, he was courageous, and he lived by his principles and acted on them despite personal consequences.”

Pfc. Thorne-Thomsen arrived in Vietnam on August 23, 1967, and quickly bonded with his unit—Alpha Company, Second Battalion, Twelfth Infantry. He wrote home that he was “glad to be in the infantry because of the lack of ‘pretension’ there.” Army buddies Charlie Page and John Stone knew him as friendly, quick-witted, articulate, and sensitive. Impressed by his abilities, Lt. Burnie Quick made him a radio operator, a vital but dangerous position.

Alpha Company operated out of Dau Tieng, between Saigon and the Cambodian border. A Vietcong supply route ran through the region, and the unit searched for and destroyed enemy bases, weapons, and food. On one mission, ordered to clear villages where the Vietcong had been hiding, it evacuated dozens of civilians, then burned down their homes. “It is justifiable in terms of winning the war,” Thorne-Thomsen wrote. “Now if we could only justify the war.”

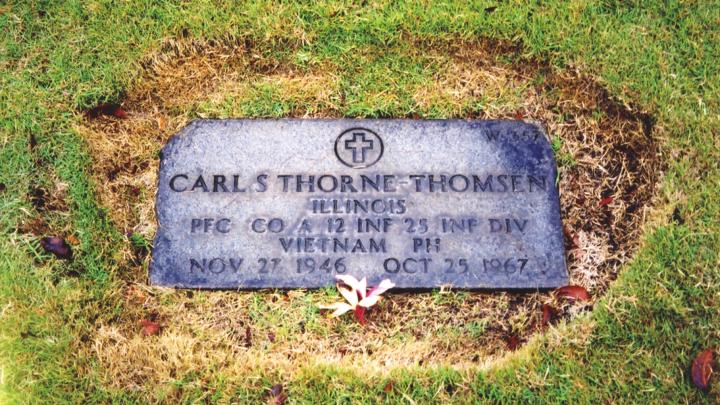

On October 25, as Harvard students protested campus recruiting by napalm manufacturer Dow Chemical, undermanned Alpha Company trudged through dense jungle. Entering a clearing of tall elephant grass, the soldiers received fire from all sides. Thorne-Thomsen repeatedly exposed himself to maintain radio contact and facilitate the unit’s maneuvers, until a grenade exploded above him, killing him instantly. When reinforcements arrived two and a half hours later, four more men were dead, and about 30 wounded.

The Crimson did not report it, but Harvard responded to Thorne-Thomsen’s death. According to an Al Gore biography, “the news swept through [Dunster dining] room like a shock wave.” The varsity lightweight crew named a new racing shell in his honor. A 1968 yearbook essay, “The War Comes to Harvard,” opened by noting that “a junior who had left Harvard last year had been awarded the Bronze Star…posthumously ‘for heroism.’ ” One of only 22 men on Memorial Church’s Vietnam honor roll, Thorne-Thomsen also received a Bronze Star “for outstanding meritorious service.”

Fifty years later, his personal act of protest elicits admiration. Leif Thorne-Thomsen, who initially viewed his brother’s reasoning as crazy, now sees his choice as that of a “remarkable man.” Crew teammate Monk Terry observes, “[It] shows a lot more strength of character than the rest of us had.” Bill Comeau, a draftee from a poor family and Thorne-Thomsen’s predecessor as radio operator, regards him as a hero for “tak[ing] the risks and mak[ing] the sacrifices to right what he considered an injustice perpetrated on the underprivileged class.” Made without fanfare, Thorne-Thomsen’s decision to forsake self-interest for principle retains the power to inspire.