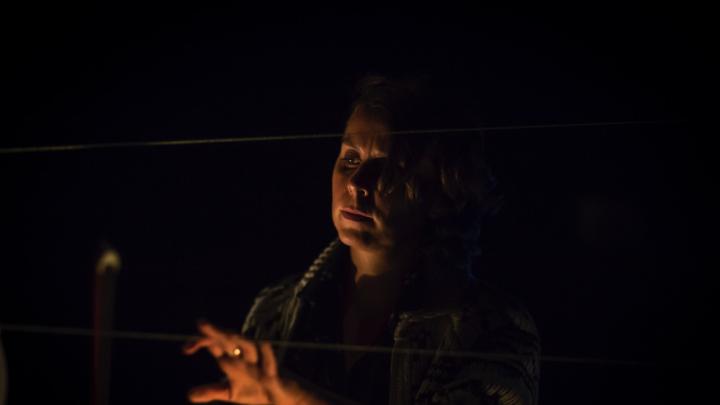

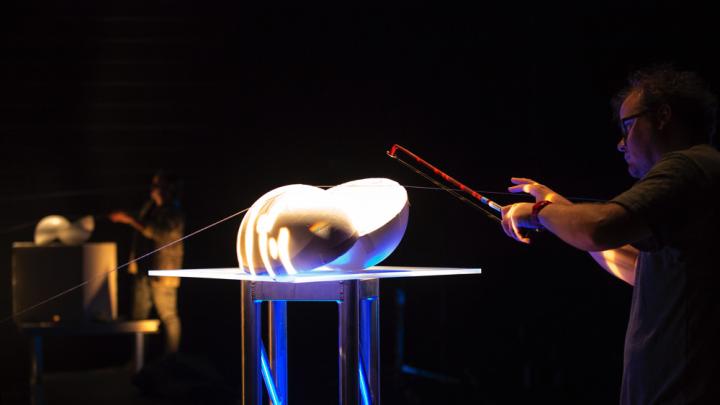

The music of composer Ashley Fure, Ph.D. ’13, asks listeners to come to terms with wanting to linger beside sounds from which they’d otherwise retreat. During an August rehearsal for her opera The Force of Things, the percussionist Ross Karre—a member of the International Contemporary Ensemble, which commissioned the work—stood behind an aircraft cable stretched across two hemispheres of styrofoam, wielding a double-bass bow. Hearing a cue through his headphones, he applied bow to cable. Metallic shrieks emanated, of the sort that kills plants and sends animals scurrying. Watching him was like watching a magician give up trade secrets, while remaining amazed: would Karre mind making that ghastly noise again?

For Fure, a professor at Dartmouth whose accomplishments last April alone—a Guggenheim, her Pulitzer finalist standing, and a Rome Prize—might suffice for a lifetime, this second complete staging of the opera since its first public performance in 2016 in Darmstadt, Germany, will be her most ambitious production yet. Previous performances were smaller-scale: at a theater in Ypsilanti, Michigan, the staging filled the space to the point of “just short of actually sawing through the walls,” Fure recalled. In the ample, readily configurable space of Montclair University’s Kasser Theater, the work—co-produced with Fure’s architect brother Adam—was “being unleashed,” she said. “Each time you revisit it, because it’s a wild, collaborative piece, it grows and sprouts new appendages.”

The Force of Things, meditating on humans’ relationship with the environment amid ecological crisis, is not an opera where singers sweat in period costume. There is no explicit plot or text. The singers make breathy, fragmented noises, as though all coherent language had rusted in their throats. From the objects and their players come groans, creaks, and screams. “I wanted to see if we could elicit pathos and emotional connection through nonhuman sources, where humans and materials are undergoing different types of evolution across the scope of the piece,” Fure explained. “What I’m trying to create is a place to sit and feel and grieve this very slow and very fast crisis that’s happening around us. And just uncomfortably, collectively—without words and messages and data and silence—just feel the volatility of it, the interconnectedness of it, and the danger of it.”

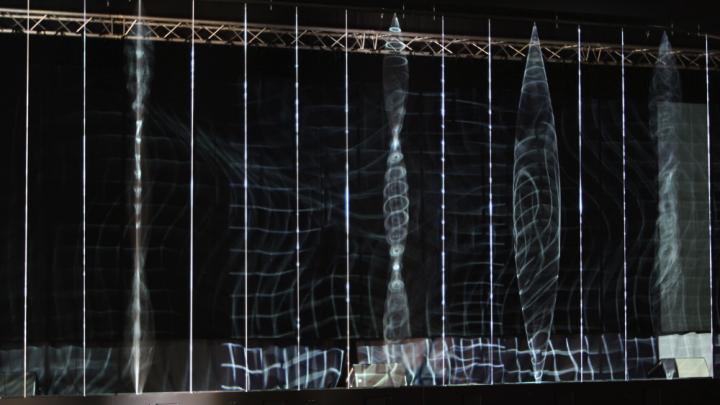

During the hour-long Kasser production (in performance from October 6 to 8), sound, light, and the performers’ physical movements guide attendees through a landscape of traditional musical instruments and inert objects, like that aircraft cable, exploited for their jarring sonic capabilities. The audience is free to move about and observe: much of the time, two singers, a bassoonist, and a saxophonist hover at the fringes, firing eldritch tones through the darkness. As in Fure’s other work, the opera drops unanticipated, often noise-laden sounds from unexpected sources into new harmonic contexts, allowing her audience to confront the possibility of expression from avenues that seem least suited for it.

With her jaunty haircut and dangly earrings, Fure is like the cool older sister, who, yes, left home to join a band, but returned with a Harvard degree to keep Mom and Dad quiet. She is at ease with what powers her art, though she cannot explain it: how her ear perks to sonic pariahs. “To me, they’re not esoteric,” she said. “I’m genuinely, viscerally turned on by them. For whatever reason, this is what I feel called to, and I’m trying to go there fearlessly.”

Fure (pronounced “fury”) grew up in Marquette, Michigan. She began composing and improvising at age four, when her parents, noting her interest in music, set her up with piano lessons. Music soon became her ticket to new experiences. Feeling held back at her high school, she won admission to the composition department at Interlochen Arts Academy, and then to Oberlin. But Fure assumed she would one day choose a field more explicitly entwined with political action—education, perhaps, or conflict resolution. Guilt about her work’s utility trailed her to Harvard, where she enrolled as a composition doctoral student directly after college. There, in a class on modernism, she discovered Virginia Woolf, whose writing eased Fure’s fraught relationship with her own work. “Woolf was the first person who taught me that you can go down to get out. She goes so deeply inside of her characters that she hits the universal through the extremely specific,” Fure said. “I have to believe that’s possible. I have to believe that the better I get at what I do—the more specific, and distilled, and exacting I can be—the greater chance there is my work might speak beyond the boundaries it’s born into.”

Concurrently, Fure began working with the microphones in the campus electronics studio. “This is what’s difficult about the concert hall for me: I want people to feel the sound right here,” she explained. “I want to whisper it into their ear. But instead I have to play it on a stage that’s 80 feet away, which always loses that crisp, intense, intimacy of proximate sound.” Being able to hold microphones right next to the sounds she was working with—like a glass tile that she placed, on a whim, inside a piano and then rotated, to earsplitting satisfaction—allowed her to create music exactly as she heard it.

The wish for closeness is present across Fure’s oeuvre: the desire to bring audiences close to netherworldly sounds they wouldn’t otherwise encounter, and to offer a catharsis born in noise. In two recent works—“Bound to the Bow,” her Pulitzer finalist composition for orchestra and electronics, and the septet “Something To Hunt”—listeners are asked to challenge hardwired listening habits. “I think,” Fure said, “I am looking for—and trying to offer—a type of empathetic engagement with material that most people in the audience, particularly those who think Stravinsky is challenging, don’t spend much time trying to engage with.”

With a few months to go before the opera’s opening, Fure was still trying to find out what sorts of new sounds the performance space allowed for, how close she could get to what she was hearing in her mind. Midway through one rehearsal, Karre, the percussionist, was testing the sound a rope made when placed inside a subwoofer (a loudspeaker that produces low bass frequencies). As he repeatedly lifted the speaker and set it down, the rope, which was suspended from the ceiling, began to twirl. It stuttered, then twirled again with renewed vigor, like a forgetful dancer.

“It’s life!” someone gasped, noting its resemblance to a double helix. “Look at the insane sound it’s making,” Fure murmured, gazing at the string with something like admiration. She seemed to have found what she was listening for: an agile whirring, slight yet tenacious, like a mind as it begins to spin.