Political and constitutional questions currently generating headlines in the national media—concerns about executive overreach, the balance of power between presidents and Congress, and access to reliable information both from and within the government—were equally troubling more than 40 years ago, when this magazine, then The Harvard Bulletin, covered a Commencement week University symposium on a fundamental issue of democracy.

~ The Editors

The Watergate case brings Americans forcibly back to a basic issue of constitutional democracy: the citizen’s right to know.

During Commencement week, four leading members of the communications industry discussed this issue in a University symposium, “its timeliness and importance transcends today’s headline,” said moderator Hartford Gunn ’48, president of Public Broadcasting Service, Washington. D.C. “Sooner or later, it was bound to come out because of the nature of our times. The greater complexity of modern life, the world-wide interdependence of all of the peoples of this planet, the growing power of governments, destructive weaponry, communications technology—these play upon the individual, his society, and his government in a way that the remarkable fathers of this country could not have foreseen.”

Besides Gunn, the members of the panel were:

John Jay lselin ’56, president of WNET-TV, New York educational television station.

J. Anthony Lewis ’48, columnist and reporter of the New York Times.

Clark R. Mollenhoff, chief of the Washington bureau of the Des Moines Register-Tribune, and former special counsel to President Nixon.

Gunn. We look today to our communications system to preserve and facilitate our need and our right to know. Yet we find that a wide range of questions and problems threatens to constrict our communication and distort the truths it must provide. For example, the proposed revision of the U. S. criminal code, making it a crime to offer or receive confidential government documents. The freedom-of-information law, and its possible abridgment by executive privilege. The use of subpoena power to command disclosure of confidential sources of information.

There are other factors, such as economic forces, that are not so visible. The increasing cost of communications, which leads to monopolies of the media, and reduction in time and space for news and public-affairs programming. Even the possible increase in postal rates may affect our access to essential information.

Finally, there’s the quality, enterprise, and courage of those who report for, edit, and control our mass media, which affects the flow of essential information.

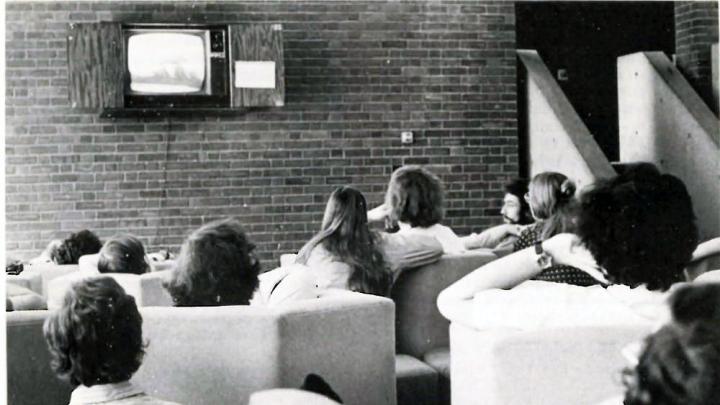

Watching the Ervin Committee hearings, it seems to me that the public’s knowledge has been advanced very significantly through access to these Senate hearings by television and radio. There are many similar opportunities with other hearings that are held in Washington. We could, and should, provide coverage of many of these other hearings, on a wide range of subjects.

But why stop with Congressional hearings? An important step in our right to know might be taken by Congress itself, if the floor debates of the House and Senate could be opened on a regular basis to television and radio. We face a serious problem—the continuing growth of the executive branch of the government, and the withering of the legislative branch. The effective use of the media by the President, and the lack of coverage of the legislative branch, could be a contributing factor to what may be a serious constitutional crisis before this or the next decade draws to a close.

If we were to make the public’s business in Congress more accessible, we might raise the level of debate among our Representatives, engage the public in such debate, and provide a small weight on the side or the legislative branch. That might be a worthwhile gift to the people of the United States on the occasion or its two hundredth birthday in 1976, more rewarding than the presently planned pageants, parades, and firecrackers.

Clark Mollenhoff, what do you see as the major issues in this question of the public’s right to know?

Mollenhoff. I think the core issue is executive privilege. This isn’t something that Nixon invented. It was invented by President Eisenhower, although he claimed there were precedents going back to George Washington. Nixon simply solidified the idea, and misused and abused it in the ultimate way. It emerged, with the full danger that is apparent in the Watergate investigations, only in recent months. The American people have available now the full glory of what a dictatorship could be. We came very close to it with the landslide election, the “four more years,” and the moves that Mr. Ehrlichman and Mr. Haldeman were engaged in last December, January, February, and in nominating Pat Gray as permanent director of the FBI. Had they succeeded in that, they would have locked in—as long as Nixon was in power—control over the FBI files, and much of the evidence that is flowing out today through the Ervin hearings.

One thing that has struck me over the years is the lack of press attention to much of the information that is available, that has been available, on all of the matters that are now coming before us dramatically in the Watergate. Obstruction of justice has taken place in essentially all of our agencies. The destruction of records, the condoning of perjury if it helps the ingroup—this has taken place in Democratic and Republican administrations over the years. It’s just worse today. Mr. Nixon, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman brought to perfection these insidious evils. That’s really all that’s happened, and it’s come to the White House, where it shocks us.

I’ve been aware of this for years, and have even been praying for a Watergate, because it would dramatize to the American people the insidious doctrine of arbitrary secrecy bound up in executive privilege.

It doesn’t make any difference what kind of freedom-of-information law you have on the books. If the executive reserves to himself the right to arbitrarily say that things will not be made public, witnesses will not be produced—then the maladministration of the freedom-of-information law is outside your purview.

You will always have misadministration of laws. What you have to have is the ability of Congress to move in and focus on these problems. This is why I feel the whole problem of government information is bound up with executive privilege.

I think the press has been soft on Richard Nixon. Soft because it opposed him ideologically, but did not oppose him on provable grounds of mismanagement and lack of due process in government—on misuse of executive privilege.

Lewis. I think the press, on the whole, has performed extremely badly over the last year. There’s much too comfortable a relationship in Washington between the press and the government, at least at the top level. It makes it hard to say to those people that they are liars, that they are violating the law every day—which in fact they do, and have done.

I also think the public is much too accepting of secrecy, and of the notion that the President of the United States knows best. That is a wrong altitude to have toward any President...and a particularly wrong attitude to have toward this President.

There is a lack of understanding on the public’s part of what is involved in freedom of the press. That it’s risky, that it’s uncomfortable, that it’s often a nuisance, that mistakes are made; but that it’s safer—as Jefferson said, if you had to choose between the government and the press, you’d rather have the press.

lselin. There has been a very public conspiracy, by all the governments in Washington during the Cold War, to defraud, deceive, and manipulate the American public. Under the guise of emergency powers, and the implied threat of marauding Communist powers from Asia to Eastern Europe, our governments have worked very hard at manipulating information.

This conspiracy has been elaborately participated in by the American press. Business is done in Washington through background briefings, unidentified sources. We have all been gulled into believing we knew a lot more than we actually did.

Until now, however, White House staff aides have tended to understand the outer limits of discretionary power. What we have seen lately is the lack of a sixth sense about discretionary power within the White House. In broadcasting, we have discovered a total lack of awareness that there should not be a concerted effort to specifically manipulate what is put out over a particular broadcasting system. We’ve also seen an effort to use FCC regulations to get commercial broadcasters to lay off doing virtually anything that would represent a critical view of people in the White House. This kind of attempt to manipulate and control information is really what has brought these guys down.

Mollenhoff. I accepted an appointment as special counsel under President Nixon, thinking of it as a chance to do something constructive. I did not realize that Haldeman and Ehrlichman had a control in the White House that was above and beyond anything that had taken place before. This was not observable from the outside. Had I written columns immediately after I returned to the outside, columns stating what the situation was relative to control over information that went to the President, control over what he read, who he saw—I would not have been believed. Only the Watergate has made that believable.

Iselin. I think there’s an important case to be made for the President’s right to know. It will be interesting, one of these days, to see the way the daily log was prepared for the President. That log, of course, is all that the President claims to read. He doesn’t have time for the newspapers and broadcasts that we see and hear. That log forms the definition of the universe that the President is thinking about.

Lewis. If you have a President who is willing to have his reading selected for him, I don’t think there’s any law you can pass that will make him read something else. One cannot imagine John F. Kennedy reading only what Mr. Haldeman and Mr. Ehrlichman decided he should read.

Gunn. No one has mentioned, as an important issue, the use of subpoena power to get at reporters’ notes and sources of information.

Lewis. Clark Mollenhoff and I may be on the minority side in this one, but I know we are both opposed to proposals for statutory protection for journalists against subpoenas. We think those are things that have to be fought out by the individual journalist and by the discipline of the newspaper or broadcasting station. Any attempt to glorify the press with some privilege that other people don’t have would be self-defeating.

Mollenhoff. This would amount to an executive privilege for the newspaper profession. I do not feel that the newspaper profession is a better place than the White House to repose that kind of executive privilege—a right not to testify.

Question from the Audience. Was special prosecutor Archibald Cox justified in asking that the Ervin Committee hearings be suspended?

Lewis. The risks involved in public examination of witnesses are very serious—not only in terms of poisoning the atmosphere of a criminal trial beforehand, but because laying out all the testimony of potential prosecution witnesses makes it so much easier for the potential defendants to arrange their lies and excuses.

On the other hand, I very strongly disagree with the notion of The Times of London, and Vice President Agnew, that the hearings should be stopped because they are injuring the constitutional rights of the people concerned. If in fact the hearings should prejudice their rights to an impartial jury, then they won’t be able to be tried. What we’re dealing with, however, is not only crime. There was here a political conspiracy—an attempt at a coup, to change the form of government in the United States in secret. To change it by installing their own man in the FBI, sabotaging the opposition in the election, setting up a secret security plan that would entitle the President to have his own unknown apparatus to spy on every citizen.

If such a thing happened in Britain, and became known, it would be debated in the House of Commons at once; it would be much nastier and noisier than anything that’s happened in this country so far, and the Prime Minister would long since have been out of office.

Mollenhoff. l have faith in Archie Cox. That doesn’t mean that I think Archie Cox, as an appointee of the executive branch of the government, should be able to shut off Congressional hearings, or shut off the press. Had the executive branch had the right to shut off the press, or the courts, we wouldn't have the revelations we’re having today on the Watergate.

Question from the Audience. Why can’t the legislative branch assert itself, and force the executive branch to follow Congress?

Mollenhoff. I have always felt that Congress is the first branch of government, and must be supported in the exercise of its proper role in oversight over the executive branch.

Lewis. Many of us, at other times, were too taken with the Presidency. We’re coming around to see the dangers of that. I think the infatuation of universities and professors with the Presidency has been entirely excessive, and very bad.

Question from the Audience. How can credibility be restored both to the Presidency and the press?

Iselin. For all our inadequacies, there’s an extraordinary strength in this society that has not been fully tapped or challenged. We have to do our damnedest to share important matters as fully and openly as we can with the public at large, and see what will come out of that.

Mollenhoff. I think the solution is an ombudsman, set up on a statutory basis so that he has absolute authority to anything and everything in the executive branch of the government. The job would have tenure, so that it would go beyond any administration or two administrations. It would have accountability. Its force would simply be in the reports that it writes, the facts that it brings to bear, the conclusions it draws, and the reasonableness of those conclusions. Had there been such a body, independent of the White House and accountable to Congress, it would have taken care of many of our problems.

Lewis. The press is perhaps now in the process of re-establishing its own standing. If it does serious work, and stops playing patsy to the executive branch, it will have done a great deal to establish its credibility. The only way the Congress can do so is not to fall over for every claim by the executive branch that unless the Congress follows what the President says, the country’s safety will be jeopardized. I can’t think of a better way for Congress to re-establish its credibility than to stop the bombing of Cambodia, something that is utterly unauthorized by law.

Lastly, I have to say something rather tough. We don’t yet know anywhere near all the facts about Watergate. But from what we do know—undisputed, confirmed by the White House itself—the President of the United States was engaged in the year 1970 in instituting a secret plan for internal security in this country, financed and carried on outside the law. In my view, our belief in the Presidency—our notion of what the Presidency ought to be—cannot be restored unless there is a different President in office.

Gunn. To sum up, then, there are probably no easy laws that can be passed to protect our right to know. Education, our institutions, the checks and balances of our government, the improvement of the press itself, are all involved.

We must all make our right to know an issue of our own personal concern. We can’t leave it to the press, the government, or the courts. It is ultimately our problem, and we’re going to have to press the issue home, every single time, or face the consequences.