David Fahrenthold’s reporting notes, digitized for online viewers, have become a symbol of resistance against the dishonesty and empty promises that defined the 2016 election cycle. In his sixteenth year as a reporter at The Washington Post, the recipient of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in national reporting took on the herculean task of tracking down then-candidate Donald Trump’s philanthropic promises and business activities. “I wanted to show people something about Trump’s character by looking through charity, which was the most obvious barometer for someone’s philanthropic impulses, what internal obligations they feel towards their fellow man,” Fahrenthold says.

Politics has not always been Fahrenthold’s beat at the Post, and he credits the wide range of topics he covered earlier in his career with helping develop his skills as a reporter. In the class of 2000’s fifth anniversary report, he wrote, “I’ve got good stories about transvestite gangs, drive-by blowgun shootings, Bigfoot researchers, and people who study bear poop.” His favorite article of all time is a 2008 story about a beauty pageant in the Chesapeake Bay area that featured a 17-year-old contestant who skinned a muskrat on stage as part the talent portion of the competition. In those first few years after graduating from Harvard, he covered both day and night police activity, as well as car crashes and shootings; later, he covered the environment. “You can define the environment beat however you want,” he says. “I decided it would mean anything that happened outdoors involving plants, or animals…or not.” When asked if he might consider a return to environmental reporting—his colleagues Juliet Eilperin and Chris Mooney spoke at the Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center in February about how to cover that subject in the era of Trump—he described covering the president’s conflicts of interests and business dealings as, unsurprisingly, a full-time job.

That job was born from Fahrenthold’s tenacity in holding the president (at the time, still a candidate) to his word whenever he boasted about his charitable giving and business operations, which, as it turned out, happened often. The Trump campaign’s lack of transparency in these areas drove Fahrenthold to keep digging, frantically, hoping to unearth the charities that had been quietly benefitting from Trump’s generosity. “He kept everything so close to the vest, his company was private, his accounts were private, his taxes weren’t released. He made it so if you wanted to write about him, in terms of accountability, you had to come to him for that information,” Fahrenthold says, regarding the challenges of digging into Trump’s famous promise to donate $1 million of his own money, along with $6 million his campaign had raised, for veterans’ organizations. Upon reaching out to Trump’s then-campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, he was informed that the recipient or date of that $1 million payment that would come from Trump’s personal accounts would remain secret.

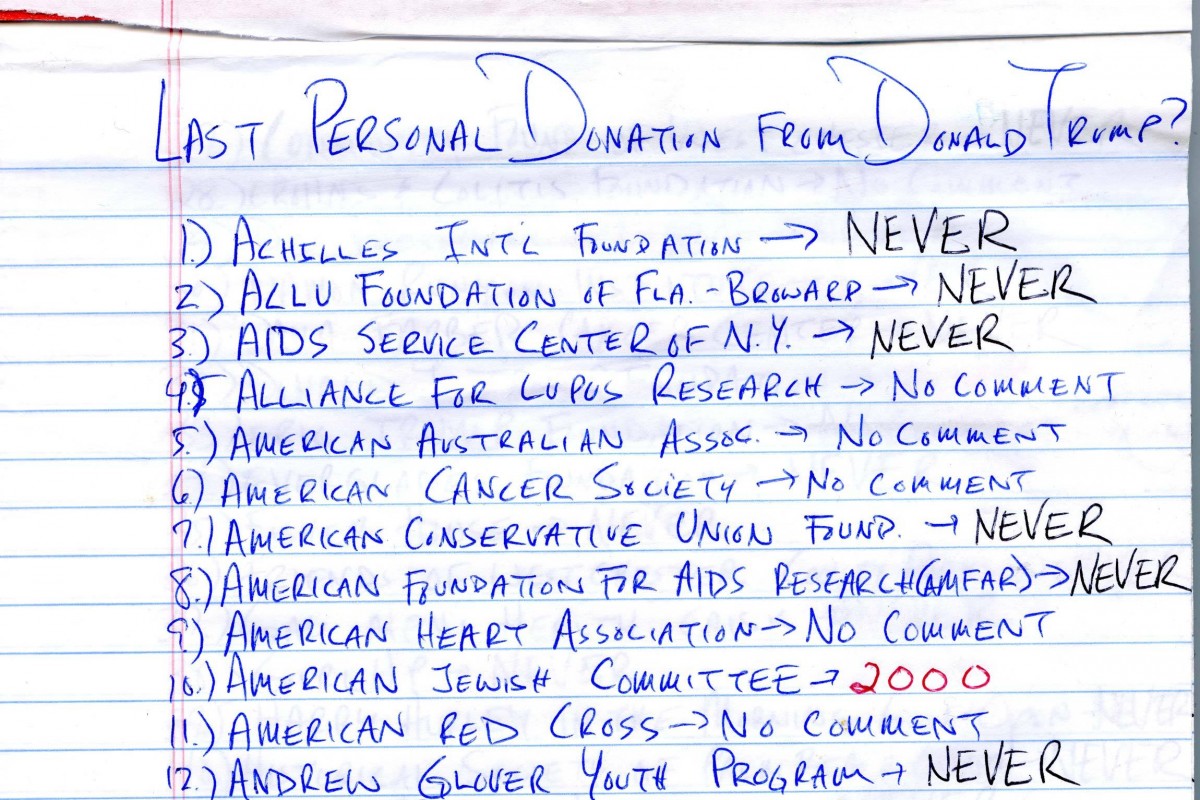

David Fahrenthold’s reporting notes from the 2016 election cycle

Courtesy of David Fahrenthold

“I could call every veterans charity in America, but that would take forever…So, why don’t I just tweet at a bunch of veterans organizations?” he asked himself. He hoped these queries would be seen not just by those groups he mentioned directly, but by others as well, some of which might disclose that Trump had made a contribution. And by adding Trump’s Twitter handle to each tweet, Fahrenthold invited Trump to play on his favorite social media platform. (Fahrenthold admits, with some disappointment, that the president has not yet directly tweeted at him. His handle is @Fahrenthold, for reference.) By election day, the Post had contacted more than 400 charities to answer one question: where were the millions of dollars Donald Trump said he had been donating going? It turned out that the single charity that eventually received the $1 million from Trump’s own pocket, the Marine Corps-Law Enforcement Foundation, did not see this money until four months after it was initially promised (and the donation had in fact not been made at the time Lewandowski claimed it was a secret), after mounting pressure from the media, including “nasty guy” (in Trump’s words) David Fahrenthold.

Trump “went to enormous lengths to avoid [making charitable contributions]. Even in relatively small dollar amounts,” says Fahrenthold. He recounts an incident in which Trump wanted to make a donation to the Palm Beach Police Foundation, which hosts a ball at his Mar-a-Lago hotel every year. Instead of contributing from his own account or that of the Donald J. Trump Foundation, he asked a recently widowed friend, who was managing her late husband’s charity, for $200,000 that he would, ostensibly, bundle with his and others’ gifts. Instead, that $200,000 contribution was, on paper, issued directly from the Trump Foundation, and the Palm Beach Police Foundation held a gala in Trump’s honor in return. “You would think somebody as rich as he was would just spend the money and save the time,” Fahrenthold says. “But no, he would rather spend the time and energy to make sure it was somebody else’s money he could give away under his own name.”

Fahrenthold’s investigations are far from over, even though the election cycle has come to an end. He says he intends to continue his newfound subspecialty as part of a team of six Post reporters who are hard at work investigating Trump’s potential conflicts of interest, including his hotels, foundation, and golf courses. In this sense, perhaps President Trump really is bringing jobs back to America after all.