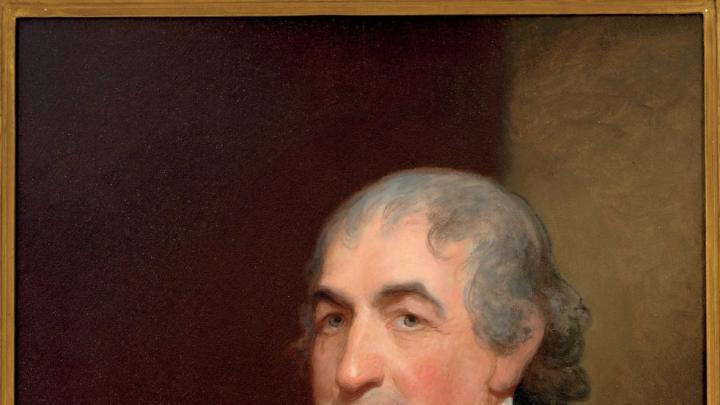

In January 1745, Caleb and Phebe Lyman Strong, of Northampton, Massachusetts, brought their only son for baptism to their pastor, Jonathan Edwards—America’s greatest theologian. For the baby, Edwards’s touch symbolized transmission of a legacy of rectitude and humility. The boy, descended from church founders, became known locally as “Deacon”; his later titles included U.S. senator and governor of the Commonwealth.

His parents sent teenaged Caleb to York, Maine, to prepare for Harvard with an alumnus, Reverend Samuel Moody. After graduating in 1764, Strong served as temporary preacher in churches near his home, but then turned to the law, despite a bout of smallpox that left him nearly blind. Apprenticed to a leading attorney, he relied on family to read him law texts, becoming a great listener. In 1772, he earned admission to the bar.

That year he publicly declared his commitment to Christ, affirming his lifelong religious devotion. Northampton townsmen promptly elected the 27-year-old as a selectman—an unusual mark of trust that proved emblematic of Strong’s career as one of the most reliable leaders in the independence movement.

When Britain’s “Intolerable Acts” closed Boston in 1774, galvanizing the colony’s resistance, Strong’s popularity brought election to Northampton’s Committee of Correspondence, Safety, and Inspection. Townsmen also sent him to the legislature and, in 1779, to the convention that wrote the state’s constitution, where fellow delegates put him on the four-man drafting committee. But Strong declined election to the Continental Congress and the state supreme court; he needed to support his growing family by practicing law.

Appointed state prosecuting attorney in Northampton, Strong strengthened his reputation in the Commonwealth’s largest county. He focused on property law—including defending people of color suing for their freedom. Like most attorneys, in 1786-87 he opposed Shays’ Rebellion, a debtors’ uprising to block foreclosures. After its suppression, legislators chose him for the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where his support for the “Connecticut Compromise,” whereby large states agreed to equal representation for all states in the Senate, helped break a critical impasse. But he left the Convention when his wife fell ill, never signing the Constitution.

When Massachusetts representatives convened to ratify or reject the Constitution in 1788, Strong provided crucial support for national government. A seaboard delegate told him, “You can do more with that honest face of yours than I can with all my legal knowledge.” After ratification, state legislators elected him to the new U.S. Senate, where he helped shape the Judiciary and Naturalization Acts, and the national bank. Reelected in 1792—Vice President Adams declared, “[Massachusetts] cannot do better…he is an excellent head and heart”—he resigned in 1796 to resume legal practice.

By now leaders throughout the state recognized Strong’s capacity to inspire confidence among sharply divided men. In 1800, a fractured Federalist Party nominated him for governor, though some objected “to the choice of a man who lives a hundred miles from salt water, whose wife wears blue stockings, and who, with his household, calls hasty pudding luxury.” He was “too frugal,” and “rides down to Boston in the stage.” But the eloquent partisan Fisher Ames ridiculed such “childish, tattling objections.” Strong, he testified, “is a man of sense and merit, and made and set apart to be a Governor,” notwithstanding his “modesty.”

The contest against another Harvardian, Jeffersonian Elbridge Gerry, was decided by just 100 votes. (In Northampton, Strong won 268 to 2 .) In victory, he was conciliatory: when, during his inaugural parade, he spied the Jeffersonian Samuel Adams standing at his doorway, Strong left his carriage and, removing his hat, walked over to shake the old revolutionary’s hand. Strong’s refusal to dismiss officials based on party won over some Jeffersonians; Federalists valued his staunch support for education and religion. Reelected annually until 1807, in defeat he returned to his practice.

His leadership resumed when Federalists called on him to block state support for President Madison’s warlike policy toward Britain in 1812. After narrowly beating his old rival Gerry, Strong refused to cede control of the Massachusetts militia to the federal government for an attack on Canada, but allowed its use to defend the state against British raids. With the war’s end in 1815, he retired for good.

Moderation, common sense, and an understanding of human frailties, not brilliance, distinguished Strong’s leadership. He supported the death penalty, but as an attorney led an unprecedented popular petition campaign to spare an Irish immigrant client, convicted of sodomy, arguing the penalty was too severe. As governor he showed mercy by granting pardons or, when a young Hindu was to hang for rape, by deporting the youth instead. In an era of fierce partisanship—sometimes leading to fatal duels—Strong’s modesty and understanding won the trust of leaders who did not trust each other. A senatorial successor, Henry Cabot Lodge, wrote that “though he was a leader in a very dogmatic party, he always expressed himself temperately, and in a fashion which gave offense to no man.” Strong supported Federalist principles, but “never pushed them in practice to a dangerous distance.”