Joe Meuse spent years drunk on the streets of Boston, sleeping under bridges, over grates, in train stations and tunnels—wherever he passed out. Occasionally he agreed to be driven to a shelter. Meuse was told he logged an astonishing 216 hospital emergency room visits in 18 months, but he doesn’t remember any of them.

“He’s been as far down the drinking path as one can go,” says Meuse’s longtime doctor, James O’Connell, M.D. ’82, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS), who first met Meuse while riding a nighttime outreach van. “I remember once thinking, ‘I don’t know how Joe is staying alive, because he is drinking so much.’ ”

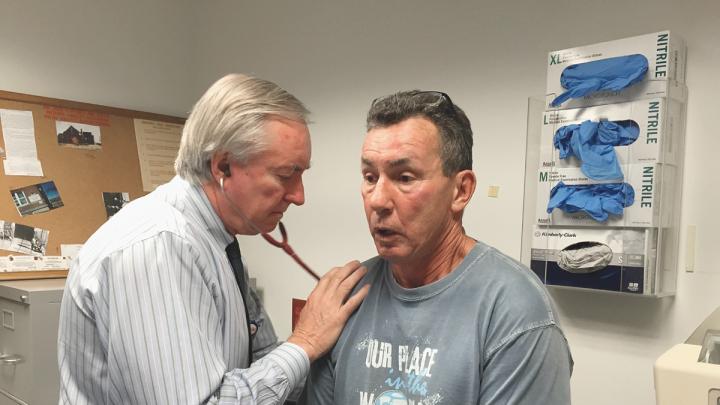

O’Connell kept reaching out and, with other supporters, eventually helped Meuse turn his life around. He recently marked five years of sobriety—O’Connell was there to celebrate—has housing, and teaches new doctors about addiction and recovery. But the years of alcohol and drug use took a toll on Meuse’s health, and on this October morning the 58-year-old former welder is visiting O’Connell in a small exam room at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Meuse recently finished treatment for hepatitis C infection, and he wants to kick his final addiction, tobacco. O’Connell checks his heart and lungs, recommends a quit-smoking patch, and admires a photo of Meuse’s dog.

“Joe is more than remarkable. He leads a really productive life now, and we all are in deep admiration,” O’Connell says. “I’m in deep admiration, too, believe me,” replies Meuse. “This is a lot better than sleeping under bridges. I never thought I’d live this long.”

For the past 30 years, O’Connell has been treating patients like Meuse as a street doctor with Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP), the nonprofit he has led since its founding in 1985. Known as “Dr. Jim,” he delivers skilled medical care with a kind and respectful touch during a weekly outpatient clinic for current and former street dwellers at MGH—the only clinic of its kind in the country. He does the same while tending to patients down alleyways, on hospital wards, in apartments, and at the organization’s health center in Boston’s South End.

Wherever he is, O’Connell collaborates with other dedicated caregivers to meet the needs of a marginalized group facing complex medical problems that are often layered with mental illness and substance use. In spite of their hardships, O’Connell says, his patients display extraordinary resilience and dignity: “It’s a blessing to get to know people who’ve been pushed to the edge,” he explains. “We take care of people who really appreciate having us around. The work is more joyful than you might expect, despite the awful tragedy.”

Joanne Guarino, 60, is a formerly homeless woman who credits BHCHP with restoring her sense of self-worth after decades of illness, addiction, and mistreatment off and on the streets. She now serves on two of its leadership boards and gives talks to Harvard medical students alongside O’Connell. “Jim is angelic. He’s so pleasant and genuine,” Guarino says. “People trust him, and he knows everybody’s name.…His compassion is overwhelming. He’ll put his arms around [homeless] people. I always think about bedbugs, but not Jim. I think God watches over him.”

Heavy-Duty Medicine

Homelessness—especially for the chronic street dwellers O’Connell focuses on—poses daunting challenges to health, including poor nutrition and hygiene; exposure to extreme weather, injury, violence, and communicable diseases; and the constant stress of being on the move. Homeless individuals, often suffering from multiple diseases, live sicker and die younger than the general population.Amid the struggle to survive, healthcare often gets pushed down the priority list.

“This is a very sick population, and this is heavy-duty, complicated medicine,” says O’Connell, editor of the widely used manual The Health Care of Homeless Persons. On a recent morning, for example, “Twenty-three of our folks are hospitalized at MGH for all sorts of things. Foot infections and pneumonia are common, and two people have subdural hemorrhages, meaning they fell down and had a bleed between the brain and skull,” he notes. O’Connell and his team treat some “exotic” conditions like frostbite and scurvy (they’ve seen patients lose fingers and feet from frostbite), “but the vast majority are things that any primary-care doctor would see [such as asthma, hypertension, or diabetes], except frequently they have been neglected for so long. So it’s pneumonia that has gotten into three lobes of the lung. What we see are the medical consequences of their poverty.”

Drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death for adults seen by BHCHP, most of them linked to opioids such as prescription pain relievers or heroin. (Opioid use has been climbing in this group since the early 2000s, reflecting the growing national epidemic.) Cancer and heart disease are close behind as the top killers of homeless adults in Boston, and the average age of death is 51, BHCHP’s research shows. More than two-thirds of the program’s patients have a mental illness such as depression, 60 percent have a substance-use disorder, and almost half have both.

On any given night in the United States, nearly 600,000 people experience homelessness and find themselves staying in shelters, motels, transitional housing, treatment facilities, cars, empty buildings, or on the streets; some 50,000 of them are veterans. The number of homeless children in the country is at an all-time high. In Boston, the city’s most recent census of homelessness, conducted one night in February 2015, found 7,663 homeless men, women, and children in various settings. A lack of affordable housing, unemployment, and poverty are the main causes of homelessness, according to a recent 25-city survey by the U.S. Conference of Mayors that included Boston. For many people, homelessness is a short-term situation triggered by an unexpected event, such as a layoff or domestic violence. But there are other, chronic, contributing factors, including low wages (an estimated 18 percent of homeless adults have jobs) and too few services to treat addiction and mental illness. Meanwhile, many shelters are full and have to turn guests away.

O’Connell describes homelessness as a prism that reveals shortcomings in society. “Refracted in vivid colors are the weaknesses in each sector, especially housing, education, welfare, labor, health, and justice. Homelessness will never truly be abolished until our society addresses persistent poverty as the most powerful social determinant of health,” he writes in his new (and first) book, Stories from the Shadows: Reflections of a Street Doctor, a collection of essays published by BHCHP in 2015 to mark its thirtieth anniversary. Filled with stories about people and situations that have shaped O’Connell’s career and commitment to social justice, the book is dedicated to his newest passion, his two-year-old daughter. “It’s been sheer magic,” marvels O’Connell, 67, about his first child.

The Core of Healing

O’Connell grew up in Newport, Rhode Island; his father, a World War II veteran, was a civilian worker at the navy base, his mother was a teacher and then a stay-at-home mom to their six children. His route to medicine was circuitous. After graduating from the University of Notre Dame in 1970 and receiving a high draft lottery number that kept him out of Vietnam, he studied philosophy and theology in England, taught high school in Hawaii, pursued a doctorate with political theorist Hannah Arendt in New York, considered a career in restaurants, and then retreated to Vermont to read, ski, and nurture friendships. During a trip to the Isle of Man, he found himself comforting a biker who’d been injured in a motorcycle accident, and, profoundly moved by the experience, found his calling. He entered Harvard Medical School at 30.

Toward the end of his three-year internal-medicine residency at MGH, several faculty members—who knew O’Connell enjoyed taking care of vulnerable people—urged him to postpone his planned oncology fellowship and instead join the city’s new homeless-health program as its first full-time doctor. He worried about making a dead-end career move, but gave it a go.

“It’s all about listening and patience….You can serve, but you can’t control.”

Right away, he recalls, Barbara McInnis—a legendary nurse who cared for homeless people at Boston’s Pine Street Inn shelter—had O’Connell ditch his stethoscope and spend weeks soaking patients’ feet as a way of building trust. McInnis (“The only true saint I’ve ever known”) imparted lessons that O’Connell has carried for three decades: Take your time. Listen to patients’ stories. Respect their dignity. Be consistent. Offer care and hope, and never judge. Address people by name. Remember that the core of the healing art is the personal relationship.

“I realized that everything I had been taught to do—go fast, be efficient—was counterproductive when you take care of homeless people,” O’Connell says during an interview in his modest office. “What Barbara and the nurses taught me early on is that you have to find ways to break in.When you see somebody outside, you get them a cup of coffee and sit with them. Sometimes it took six months or a year of offering a sandwich or coffee before someone would start to talk to me. But once they engage, they’ll come to you any time because they trust you.…I often say that the best training I had for this job is having been a bartender. Because it’s all about listening and patience and realizing that you don’t have much control over the situation. You can serve, but you can’t control.”

O’Connell found the work so satisfying that he scrapped plans for the oncology fellowship, and one year turned into 30. Under his leadership, BHCHP has evolved from a pilot project, launched in 1985 with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, into the largest and most comprehensive such program in the country (there are 240-plus federally funded Health Care for the Homeless organizations) and a model for quality and innovation (see “Vulnerable Patients, Quality Care,” opposite).

As president, O’Connell works on strategic planning and fundraising for the organization, and advocates at the local, state, and national levels on behalf of homeless people: discussing, for example, how new payment systems under healthcare reform will affect that population, or the urgent need to expand affordable housing and supportive services. He considers policy issues with a critical eye, bringing to bear his experience as a physician and national leader in his field, says program CEO Barry Bock, a registered nurse who has worked with O’Connell for more than 25 years. “First and foremost, Jim is a physician focused on social justice. When you sit with him and talk about policy ideas, there are a million ‘whys.’ Why would we approach it this way? How does it serve people better?”

BHCHP chief medical officer Jessie Gaeta says O’Connell has a knack for translating what he sees on the street with patients into a bird’s-eye view of homelessness in Boston and beyond, “and into a vision for strategic direction and opportunities for policy decisions we should be advocating for.” On a personal level, she notes, O’Connell makes others feel valued.“He is always looking at what he’s going to learn from somebody. Sitting on the other side of a conversation from him, you always feel like you’ve got something important to say, whether you’re a patient, or a colleague, or a legislator.”

Once, Gaeta recalls, a newly housed patient paged O’Connell about 10 times in one day for support. “And he called her back every time. I remember sitting in my office at 7 p.m. on a weekday, desperately trying to finish work. I hear Jim call back, and with the most patient voice, he walks her through how to cook spaghetti. He went through it step by step, how to make spaghetti and the sauce. I just sat there smiling to myself. This is an unusual person.”

O’Connell was equally accessible to Guarino, the patient who co-chairs the program’s consumer advisory board, when she became frighteningly sick in the middle of the night several months ago. As she tells it, “I called Jim and woke him up. I said, ‘What am I going to do?’ And he said, ‘You’re going to Mass General right now, Joanne.’ My sister got me there, and the doctors were waiting for me.…at two in the morning, they were waiting for me. I felt like the president of the United States.”

A Father Figure

O’Connell has won numerous awards for his humanitarian work, published in prestigious medical and public health journals, appeared on Nightline and National Public Radio’s Fresh Air, and given speeches and conferred with colleagues around the world. He was invited to the Obama White House during the healthcare reform debate as an expert on homelessness issues. But to the struggling men and women he visits on foot or aboard the Pine Street Inn’s nighttime outreach van, O’Connell is simply a steady presence, there to comfort.

On a blustery Friday morning last fall, O’Connell arrived for his weekly “street team” check-in with patients, trim and wearing a button-down checked shirt, casual pants, and a New England Patriots cap. As soon as he emerged from a bagel shop near MGH, homeless people gravitated toward him. “Everybody knows Jim. It’s just the way it is,” said Steve Henderson, 53, rolling up in his motorized wheelchair with a bandaged leg. “He’s always in a good mood. He’s a caring person.”

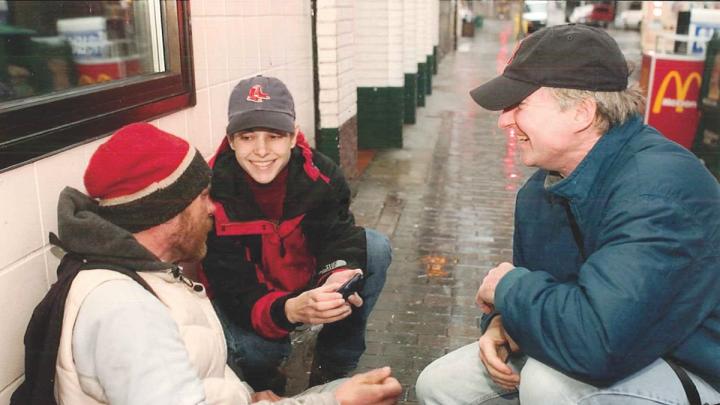

O’Connell talked with Henderson and then huddled with a young woman who had arrived visibly distressed, with a face that appeared swollen and battered. Dr. Jim lined up safe shelter and treatment for her at Barbara McInnis House, the program’s medical respite unit. Then he headed up Cambridge Street wearing a small backpack containing basic medical gear, like a thermometer and blood-pressure cuff. Accompanying him that week were psychiatrist Eileen Reilly and Katie Koh ’09, M.D. ’14, a psychiatry resident in the MGH/McLean Hospital training program who said she considers O’Connell a role model. The team carried food and pharmacy gift cards for handing out, along with a bag of clean white socks for feet that may be suffering from exposure or ill-fitting shoes. That day, O’Connell and his colleagues did more chatting than hands-on doctoring, but whenever they happen to find someone in crisis, they do their best to arrange detox or other emergency care.

In a small park, O’Connell hugged Mundo, a 46-year-old homeless man who said he was dealing with insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and alcoholism, and had been in trouble with the law. He appreciated the street team’s support: “They come around and take care of your feet, make sure you got clothing, make sure you have accessories, hygiene-wise and food-wise.” He has known O’Connell for about 15 years and said, “It’s like talking to a father figure, an uncle, a best friend. He’s my primary-care doctor, but you can just talk to him, be open. It’s just real.…Everybody has their faults, but I haven’t seen faults.”

“You…can’t solve homelessness without housing, but you need much more than housing to solve it.”

The number of chronic street dwellers in Boston has been falling (estimates range from under 150 to 350) as more qualify for subsidized housing that also includes support, like a resident case manager. “I’m a street doctor, but our team now spends half our time visiting people in their homes. It’s really great,” O’Connell says. On the other hand, he pointed out, housing poses new concerns for this population. “Our experience has been that, now that they’re in housing, all the furies that pursued them on the street don’t go away—and in many ways become magnified—when they’re alone in their studio apartment. The loneliness and desperation we can see wasn’t as visible when they were out on the streets—because they had a role there. You realize that you can’t solve homelessness without housing, but you need much more than housing to solve it.”

Only a Doctor

O’Connell is proud of BHCHP’s role in integrating its potentially marginalizing clinical work into the mainstream. “When I started doing this job, there was no real professional career path to take care of homeless people and stay part of the academic community that I cherish,” O’Connell recalls. “I believe that what we’re doing is at the core of medicine and who we are as healers and providers.” One success story he cites is former BHCHP chief medical officer Monica Bharel, M.P.H. ’12, who last winter became commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

His position, he says, has always defied routine. “Every time you think you know what you’re doing, something happens and you’re wrong—and you have to start all over again.” There have been setbacks and sorrows: during the mid 1980s, for example, twin outbreaks of tuberculosis and HIV hit the shelters and the team watched, devastated, as patients died horrible deaths from AIDS with virtually no treatment available at the time to help them.

His patients continue to provide daily inspiration, and compiling Stories from the Shadows gave O’Connell a chance to celebrate their lives—but also to underscore the crushing weight of poverty. O’Connell says he has more stories stashed away in boxes for the next book, if there is one.

He mentions an elderly man he met in the mid 1990s during street rounds at South Station. “Robert” was a voracious reader, and O’Connell eventually learned that this disheveled man had once taught English and philosophy at Columbia University and socialized with Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation writers. But schizophrenia sent Robert roaming the streets of America for decades, lost to his family. “He was very furtive. When I finally connected with him, it was only over philosophy,” O’Connell recounts. “He would come into the clinic, and I couldn’t take his blood pressure—he wouldn’t let me do anything medical—but I would make sure his appointment was during lunch break, and we would sit and talk. Robert was the most brilliant man I have met on the streets. He had an astonishing memory and could speak in depth about virtually any book or philosopher I would mention.” When Robert was hospitalized for shortness of breath, O’Connell called his sister and they spoke for the first time in ages; they were both close to 80 years old. “After we placed him a nursing home, his family visited frequently and were with him when he died,” O’Connell says. “It was quite tender and wonderful.”

O’Connell remembers the rage he used to feel about homelessness and his sense that he should focus on eliminating it. “Then I started to realize, I’m only a doctor, and I can’t do that. Many folks who come and do this work want to fix homelessness, and when they can’t, they get disheartened. The ones who make it realize that our job as doctors is to ease suffering. Then it becomes about the stories. You realize, ‘These people have gotten under my skin, and I want to take care of them.’”