With only a couple of hours to go before the opening reception for Damon Krukowski: NOT TO BE PLAYED—an exhibition at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts exploring the strange saga behind an obscure audio recording of Ezra Pound’s “Bloody Sestina”—curator Damon Krukowski ’85 was still deliberating whether to hand out printed copies of the poem itself. He knew visitors would be curious to read it, but he didn’t want to distract from his more central purpose: to make them hear it.

“People don’t think of poetry these days as a spoken form,” he said as gallery staffers wheeled past with bottles of wine for the reception. “But there’s so much in the audio of this poem that you just don’t get from the text.”

“Sestina: Altaforte”—its nickname came later—was written in 1909 by a 23-year-old Pound, then living in London and fascinated by medieval troubadours. He constructed the poem as a (very) dramatic monologue in the voice of Bertran de Born, a twelfth-century troubadour, nobleman, warrior—and warmonger. Borrowing imagery from de Born’s own poetry, it scorns “womanish peace” and declaims the joy of battle, of clashing swords and fields run red with blood. “Bah!” reads one line. “There’s no wine like the blood’s crimson!”

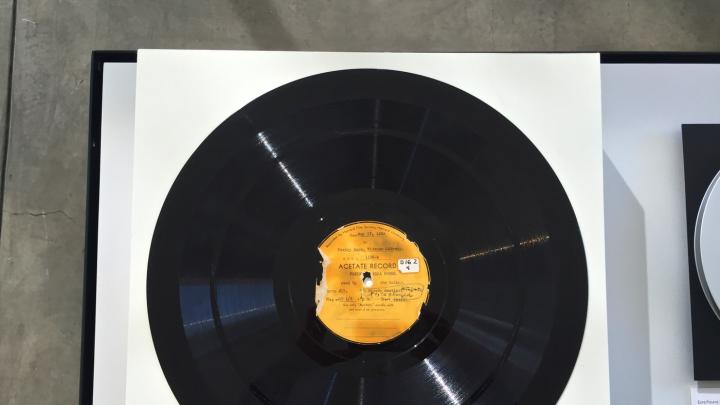

Pound recorded the poem only once, in May 1939, for the Harvard Vocarium, one of the first-ever poetry record labels, founded in 1933 by assistant professor of public speaking Frederick C. Packard Jr. Standing with Packard in a small (and reportedly sweltering) alcove in Harvard’s Memorial Hall, Pound didn’t so much recite the poem as devour it, banging a kettle drum as he growled, and sometimes shrieked, the words in his adopted Irish brogue.

After that visit to Harvard, which also included an hour-long reading to students, everything fell apart. War broke out in Europe, and Pound, who’d sailed home to Italy—where he had moved in the late 1920s and become an adherent of Mussolini—gave a series of propagandist radio broadcasts championing fascism and anti-Semitism. After the war, he was arrested as a traitor by American troops and famously held for weeks in an outdoor steel cage before suffering a mental breakdown and being hauled back to the States, where he was incarcerated at St. Elizabeths, a psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C.

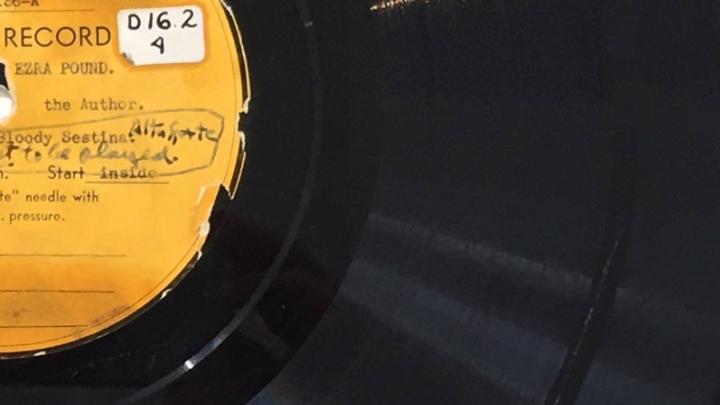

Then in 1955, in response to a permissions request for a broadcast of his 1939 recording, Pound sent a note forbidding the “Bloody Sestina” audio from being circulated. The rest of the two-and-a-half-hour reading he did with Packard could be disseminated, but that one poem, he wrote, was “NOT TO BE PLAYED.” Ostensibly the reason was that its bloodlust might provoke violence, but Krukowski says Pound’s motivation was perhaps more practical: he was lobbying for release from St. Elizabeths, and likely worried that the sound of his voice delivering a full-throated, first-person, pro-war fantasy might hurt his already precarious position. (He was freed in 1958.)

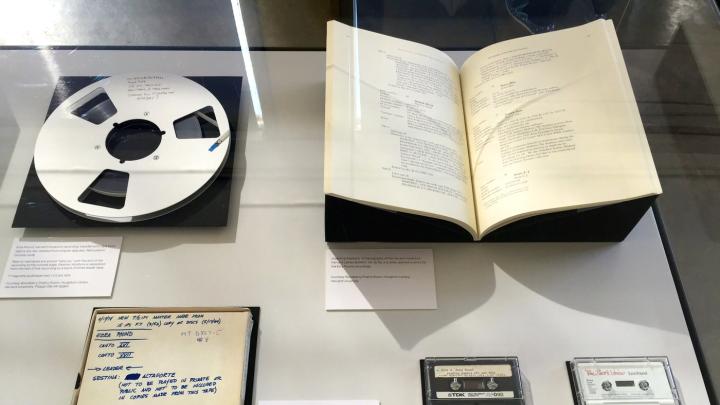

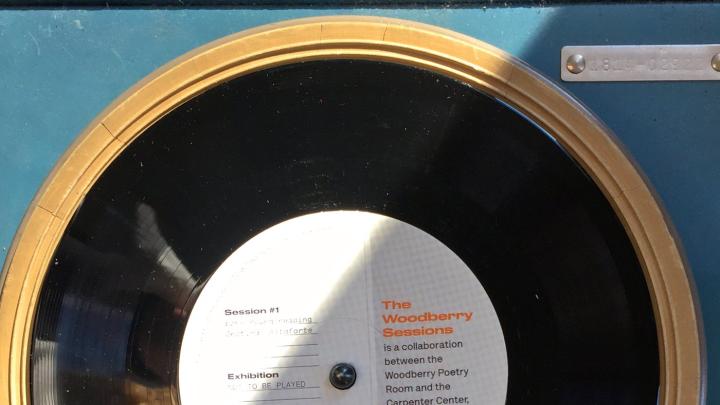

The Carpenter Center exhibit chronicles how the staff of Lamont Library’s Woodberry Poetry Room, which now houses the Vocarium’s archive, coped with Pound’s interdiction across the decades, as acetate records gave way to reel-to-reel magnetic tape and then to compact cassettes. Laboring to preserve the poem’s audio from one medium to the next—while keeping it segregated from the rest of the recording—the Woodberry curators periodically appealed to Pound and his family to end the prohibition. In 1978, six years after Pound’s death, his daughter, Mary de Rachewiltz, finally lifted the ban. The exhibit includes letters dating to the 1950s, Packard’s 1939 datebook noting his appointment with Pound, and archival copies of Pound’s recording on various media, all bearing dutiful hand-scrawled admonitions about the “Bloody Sestina.” While assembling the exhibit, Krukowski and Christina Davis, current curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room, also discovered several small, seemingly intentional scratch marks on the 16-inch lacquer disc from 1939. Pound’s voice isn’t scratched, only the blank space preceding the sestina, so if the record were playing from beginning to end, the needle would skip before the forbidden track.

As a Harvard undergraduate, Krukowski spent many hours inside a pair of headphones in the poetry room, listening his way through its hundreds of poets—the Modernists, the Beats, the New York School, the Confessional poets—on the record turntables that then populated the room. “I was teaching myself poetry,” he says. He didn’t hear the “Bloody Sestina” until later, and for him that recording crystallized something about the poet. “Pound has always been a problem,” he says, citing a push-pull of admiration for his work—“Because of Pound, I took a class at Harvard in grad school in Occitan” (the language of the French troubadours)—and revulsion at his politics and his intense, almost absurd, machismo. “I heard the recording of the ‘Bloody Sestina,’ and it was like all of it in one,” he recalls. “It’s Pound in all his affectations, flailing about.…And yet, he was a great American poet—a great American poet. And that’s here, too.”

Most famously the former drummer for the indie-rock trio Galaxie 500, Krukowski now performs with his wife, bassist Naomi Yang ’86, as Damon & Naomi; he is also a poet and essayist who has taught sound and language courses at Harvard and is a fellow this academic year at the University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society. The Pound poem’s long peregrination raises compelling questions, he says, about the shift from analog to digital media; he is at work on a nonfiction book, due out in 2016, about that shift to digital in the music world. In the “Bloody Sestina,” he finds a parallel.

“There’s something about the recording of the voice in analog technology—when you hear Pound’s voice on this record, you hear all these nonverbal aspects”: breaths, sighs, hesitations, the sound of the room, the quality of air, the tension of inhabited silence. “And we respond to those things in a very human and detailed way, because we’re really good at decoding people’s tone and the way that they’re speaking. Their anxiety level, their sense of authority, their sense of themselves—you hear a whole lot that has nothing to do with what’s being said.” Digital processing, he says, eliminates all that in favor of delivering the words themselves more clearly and efficiently. That’s why conversations on a cell phone don’t have the same richness and intimacy as those on an analog phone, why pop singers’ voices now seem to arise out of nowhere, erupting out of a “digital black” without air or space or sound.

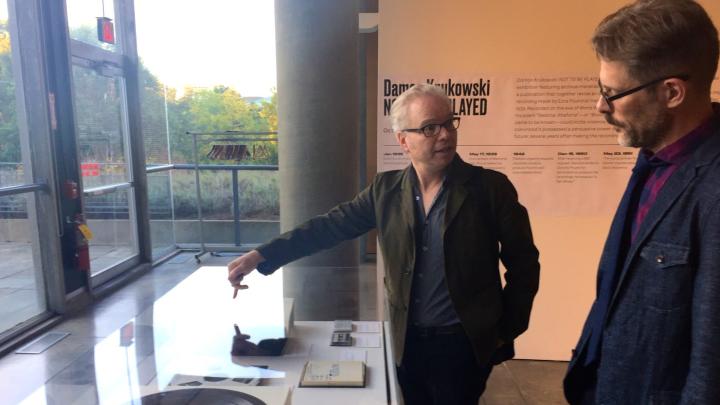

A collaboration between the Carpenter Center and the Woodberry Poetry Room, the exhibit is the first in a series that Davis and Jim Voorhies, Robinson Family director of the Carpenter Center, are calling The Woodberry Sessions. “We wanted to find a way to activate the archives,” Davis says. “To have people be directly connected with archival materials, but not in a way that makes you feel you’re not allowed to touch them.”

Anchoring one corner of the gallery is a blue plastic record player on which visitors are encouraged to play the once-forbidden audio. When they do, the almost hypnotic sound—a roiling wave of language punctuated by staccato bursts and occasional drumbeats—fills the room. Pound’s words themselves are hard to make out, but that hardly seems to matter; the grandeur and emotion and meaning is unmistakable. (The exhibit program includes a vinyl disc of the “Bloody Sestina” for visitors to take home.) “The idea was to put people in touch with the material forms that the sound has taken over time,” Krukowski says. “And let people literally look at that—which you don’t always get to see—and consider what kinds of issues that raises for Pound’s voice, for the poet’s voice, for public speech at large, for political speech. What are the relationships?”

“This is exemplary of the connections the Carpenter Center can make,” Voorhies says of the exhibit. “Bringing archival material out into the public realm, and through the lens of contemporary artists like Damon.…For me, it demonstrates the rich field of contemporary art, that contemporary art is this space where lots of questions can be asked.”

In the end, Krukowski decided to omit the printed copies of the poem. “To me the sound is very immediate,” he said, “very revealing. On the page I don’t see it. On the page I see something else.”